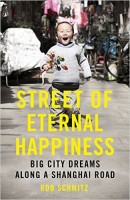

Street of Eternal Happiness: Big City Dreams Along A Shanghai Road

by Rob Schmitz

(John Murray, £20)

The big picture isn’t always the most revealing one. Sometimes you learn more from concentrating on the small things. So it is with Street of Eternal Happiness, in which an American reporter, charged with explaining the Chinese economy, talks to the people along his road who help to make it tick. The result is educational and entertaining, engaged and dispassionate, all at the same time.

The big picture isn’t always the most revealing one. Sometimes you learn more from concentrating on the small things. So it is with Street of Eternal Happiness, in which an American reporter, charged with explaining the Chinese economy, talks to the people along his road who help to make it tick. The result is educational and entertaining, engaged and dispassionate, all at the same time.

Rob Schmitz first visited China to teach English as a Peace Corps volunteer at the turn of the millennium. Fifteen years later he returned as a correspondent for American Public Media’s Marketplace, a programme with more than 10 million listeners a week. Coverage of China, he feels, focuses too much on the government or the economy, which is now the second-largest in the world. If you make an effort to understand the hopes and dreams and fears of the people, he argues, you can have a better understanding of the country as a whole.

That’s what he set out do do over four years or so from 2010, among the residents of Changle Lu, or Long Happiness Street, which he took to calling the Street of Eternal Happiness. The people he features are not just cyphers, chosen to illustrate some aspect of the economy and identified by name, address and age. They are fully rounded characters, whose stories emerge in chat after chat, chapter after chapter, so we feel we are getting to know them as the writer does.

The book, which started life as a radio series, is rich with voices. Among them are those of “Uncle Feng” and “Auntie Fu”, who serve up the best scallion pancakes in the district. He’s a man who was conned by party propaganda in his teens and is determined not to be fooled again; she wants to be rich, and falls victim to one investment scam after another. Here’s a couple who have been bickering since the days of Mao, and, because they can’t even agree on what to watch, have two television sets in their bedroom.

One of the youngest characters in the book is Chen Kai, an entrepreneur in his thirties who likes to be known as “CK”. He survived an abusive childhood in an industrial part of the country to prosper at school and makes a good living from selling accordions and running a sandwich shop, but he comes to feel that his life is missing a spiritual element and, in common with many of his generation, turns to Buddhism.

One of the older ones, 61-year-old Xi Guozhen, is preoccupied with the past rather than the future. Her husband was killed when their home was demolished to make way for the high-rise where Schmitz now lives. For 20 years, she has been petitioning the government to investigate his death, and has been jailed numerous times for her pains.

Many China-watchers have long argued that, with capitalism flourishing, an independent legal system would gradually evolve alongside it; Xi’s experience suggests they might be overly optimistic.

Schmitz speaks both to those who are prospering under the new economic freedoms and those who, not so long ago, were sent to labour camps for being “capitalist lackeys”. His interviewees, several of whom have clearly become friends rather than just contacts, speak freely and frankly, and only a couple have asked him to conceal their real names and addresses. One wonders what some of those who feature will make of his book if they are allowed to read it. One mother says to Schmitz of her daughter-in-law: “If my son were as tall as you are, he wouldn’t have settled for her. She’s not that pretty.”

Schmitz says modestly that the more he learns about the Chinese economy the less he reckons he knows. Readers, though, on closing his book, will feel much wiser about China and the Chinese than when they started. MK

This review appeared first in The Daily Telegraph

Leave a Reply