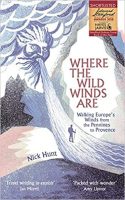

As a child of six, NICK HUNT was almost carried off by a gust of wind in the Great Storm of 1987. Nearly 30 years later, he had a daring idea for a travel book: to follow four of Europe’s named winds across the continent. The result, ‘Where the Wild Winds Are’, was short-listed for Stanford Dolman Travel Book of 2017 and is now out in paperback. In this extract, the author reports on his encounter, in Split, with the Bora

As a child of six, NICK HUNT was almost carried off by a gust of wind in the Great Storm of 1987. Nearly 30 years later, he had a daring idea for a travel book: to follow four of Europe’s named winds across the continent. The result, ‘Where the Wild Winds Are’, was short-listed for Stanford Dolman Travel Book of 2017 and is now out in paperback. In this extract, the author reports on his encounter, in Split, with the Bora

YOU WAIT three weeks for a Bora, then two come along at once.

The first one woke me at five in the morning, and it was Black. There was a bellowing in the streets, and gobs of rain smacked down like ripe fruit; a few plucky passers-by staggered beneath umbrellas. ‘Bora?’ I called to the nearest one, who ploughed onwards without response, but the next raised his head. ‘Crna Bura!’ he yelled. ‘Black Bora!’ This was the rarer variety, which I had not expected to meet — caused by a centre of low pressure in the southern Adriatic known as a Genoa Low, bringing dark skies instead of clarity — but whatever its colour its strength was enough to heave me backward in the street. Half asleep, wrapped in waterproofs, I waded through the air.

The city was newly populated by sounds that had moved in overnight — the rolling and scraping of displaced objects, the jangle of masts from the marina, water surging everywhere — and cars crawled down the road with wipers blindly thrashing. The wind came in short, aggressive gusts, rushing thuggishly through the streets; stepping around certain corners was like being shoved by invisible assailants. Dodging shrapnel, I climbed the steps, rapidly turning to waterfalls, that led to the top of Marjan Hill, conscious only of wanting to be exposed beneath the sky. At the summit a concrete plateau rose above flailing pines. The Croatian flag on its pole roared like an uncontrolled fire, convulsed by violent ripples. Scaling a wall to see the sea, I was at once thrown off again. It was too strong to stand against; too strong even to look at. My lips and eyebrows were numb with cold. I was stupidly happy.

Then the Black Bora departed, and the White Bora took its place.

The first thing I knew of this transition was the change in the light. The dark clouds suddenly fled, leaving clarity in their wake. Villages that were invisible before leapt into focus on distant coastlines, every detail picked out cleanly, and the horizon went from a smudge of crayon to a sharp pencil line. The sea was lucent, silver-flecked, the waves driven off shore like animal fur smoothed the wrong way; giant cat’s-paws ruffled the surface, spreading fanwise to the south. Turning inland I saw, with shock, a monstrous snow-covered mountain that hadn’t been there before. It appeared to swell as I looked, growing brighter and bolder in all dimensions, as the ranked apartment blocks shrank before its size. It might have been Hyperborea — the mythical land that the ancient Greeks believed lay ‘beyond Boreas’ somewhere in the far north, a place of perfection and purity — but as the vision consolidated I realised it was Mosor. Yesterday it had been brown; now it was blinding white.

At the bottom of the hill the citizens of Split were inspecting the damage, walking their dogs, scurrying from shop to shop clutching supplies to their chests. Workers were out with rush brooms, sweeping away the debris. Pigeons rattled in disturbed flocks, keeping close against the walls. Everything had been disarranged, the very air unsettled. I bumped into my landlady, who was in an exuberant mood. ‘That was Black Bura, now we have White. You should climb Mosor this afternoon — when Bura blows, you can see Italy. Take a bus to Gornje Sitno and keep going up . . .’

The following day, in dazzling sunshine, I would see crowds surge through these streets for the start of carnival. Children in fancy dress — superheroes, devils, pirates, witches, soldiers, punks, princesses — would process through the crumbling lanes, and bands of masked and antlered mummers, with cowbells clanging from their waists, would perform a slow and sinister dance to the drone of goatskin bagpipes. These pagan Zvončari, whose task it was to hasten spring and drive away evil spirits — invading Moors and Turks included — were the shaggy monster-men of the mountainous hinterland, stamping and snorting their way down upon the civilised coast. I would see the city transformed, the well-behaved giving way to the wild, stirred to passion as much by the wind as the Resurrection.

But for now I was heading to Mosor, and my appointment with the Bora. I took a bus through the outlying suburbs and into the Dinaric Alps, where streams tumbled under bridges and vineyards terraced the slopes. It was a new white world up here. Gornje Sitno was the highest village, the end of the road. Six inches of powder snow squeaked under my boots as I climbed, snowballing at the tips of the laces, making lion’s tails. The snow had favoured the windward side of every leaf and blade of grass, while tree trunks and telephone poles were vertically scored with a furred white line angled precisely north-east, as if magnetised to a new pole. The world had been perfectly bisected, divided between spring and winter.

Sheltered by the slope at first, I could only hear it. But then I reached the top, and the Bora was upon me.

It was on my skin, freezing my face, blizzarding into my eyes. My eyelashes were frosted, my beard stiff with ice. I made the mistake of removing my mittens and my fingers throbbed so much it felt as if they’d been slammed in a door. The chill of it pushed me back, forced me to proceed in a crouch, as if advancing under fire. Or as if I was bowing.

It was in my ears, but it wasn’t blowing; nor was it moaning, whistling, howling, or any of the other words usually used to capture wind. It was less a sound than a sensation, a nameless energetic thing that erased the line between hearing and feeling; for the first time in my life, I understood sound as a physical force. It was in my lungs, under my skin. Like a religious maniac, I roared my appreciation.

The Bora roared right back at me, and the mountainside ignited. An eighty-mile-per-hour blast lifted veils of powder snow, frozen spindrift that swirled like smoke, spinning itself into ice tornadoes that leapt from slope to slope before blowing apart again in mists of agitated dust. It happened again and again as I watched, each white eruption spreading and merging to create gyrating clouds that travelled as fast as a forest fire, hurtling down the mountain. The Bora’s face was visible in each fleeting pattern of snow, each convolution and curlicue, each vortex, twist and coil. I saw the invisible appear, the formless given form.

What did the Bora say to me, on that frozen mountainside?

I could not read its words. Its language was too large.

Extracted from Where the Wild Winds Are by Nick Hunt, published in paperback by Nicholas Brealey at £9.99.

Extracted from Where the Wild Winds Are by Nick Hunt, published in paperback by Nicholas Brealey at £9.99.

© Nick Hunt, 2017.

Nick Hunt has walked and written across much of Europe. He has contributed to The Economist, The Guardian and other publications and works as a storyteller and editor for the Dark Mountain Project. Both his first book, Walking the Woods and the Water (Nicholas Brealey, 2014), and Where the Wild Winds Are were short-listed for Stanford Dolman Travel Book of the Year. He currently lives in Bristol.