We’d escaped to the seaside. There was a playground here; there were long breakwater walls to walk on, shells to gather. So why, Matilda wondered, was Grandad spending so long looking at big photos on the prom of people hovering at their front doors?

She humoured me for a minute or two. Had her brother been with us, things might have been trickier. But Arthur, not yet four and too speedy on the stairs, had tumbled down them, put out a hand to stop himself, and today had a wrist so painful he wouldn’t let anyone touch it. His dad needed to take him to casualty, and his mum needed to go to work. Which was why, breaking free for a while from pandemic-enforced perimeters on the second Saturday in October, Teri and I had taken six-year-old Matilda to Worthing.

It was becoming a regular outing for the two of us. Teri was winding down in her job — nursing at a school for children with special needs — and I no longer needed to be half an hour by train from London. We’d been talking for a few years of moving farther from the capital and nearer the coast, but staying within an hour-or-so’s reach of our daughters in Surrey. One possibility had been the market town of Horsham, about 30 miles south-west of London and 18 miles north-west of Brighton. Horsham is on the A24, and at the end of that road, on the edge of the sea, is Worthing. We’d had a walk round Horsham one day, and liked the feel of it, but that was as far as we’d got. Why stop here, Teri said. Why settle for living near the coast when we could live on it? In Worthing, she meant.

She was sold on Worthing. She’d moved there with her family from Birmingham at the age of nine, and lived there until she was 13. She loved her new house, her school, her town, but most of all she loved the sense of space she found on the edge of that town. She could wander a beach that seemed to go on for ever; she could pack a sandwich, hop on her bike, and disappear with her best friend into the green heaven of the South Downs. Until 2020, she’d been back to Worthing only a couple of times since her childhood, but Worthing was still in her. I could hear it in her voice when she was trying to sell the place to me. I could see a new light in her eyes when we were there. A Worthing light. I wasn’t quite so dazzled, but she was working on me, taking me on trips that were part scouting, part sales pitch.

Today, Teri had arranged to meet an old friend, Hazel, who had moved here a few years earlier from Sutton, so we could have a socially distanced chat outside a café and Hazel could work on me too. But Matilda wouldn’t want to sit about for long. We decided that Teri should hook up with Hazel on her own, while Matilda and I headed for the playground and the pier.

All around us were people out for their Covid constitutional: runners, walkers, cyclists, dog-walkers. Quite a few of the walkers paused, as we had, by a refurbished shelter, its walls both prom-side and sea-side hung with an exhibition by Barry Falk, a local photographer. He called it “Undiagnosed” because many of his subjects, his friends and neighbours in the town, hadn’t tested positive for Covid but were having to behave as though they might have it. They weren’t in quarantine, but they were having to cut themselves off from others. All of them were posed on their front doorsteps. They looked out, as if, maybe, they had been hopeful of escape and then new restrictions had suddenly descended.

“Can we go on to the pier now?” Matilda asked. She raced ahead of me. Every 50 yards along the railings there was someone with a fishing rod, and, here and there, a rod unattended. “Can I have a go?” Matilda asked, and I had to explain that the rods would have owners, and the owners would be back any minute to check if they’d had a bite. I promised her that we’d have a go at fishing next time we made it to Cornwall, where her dad had grown up, or Portstewart, where Grandad had grown up.

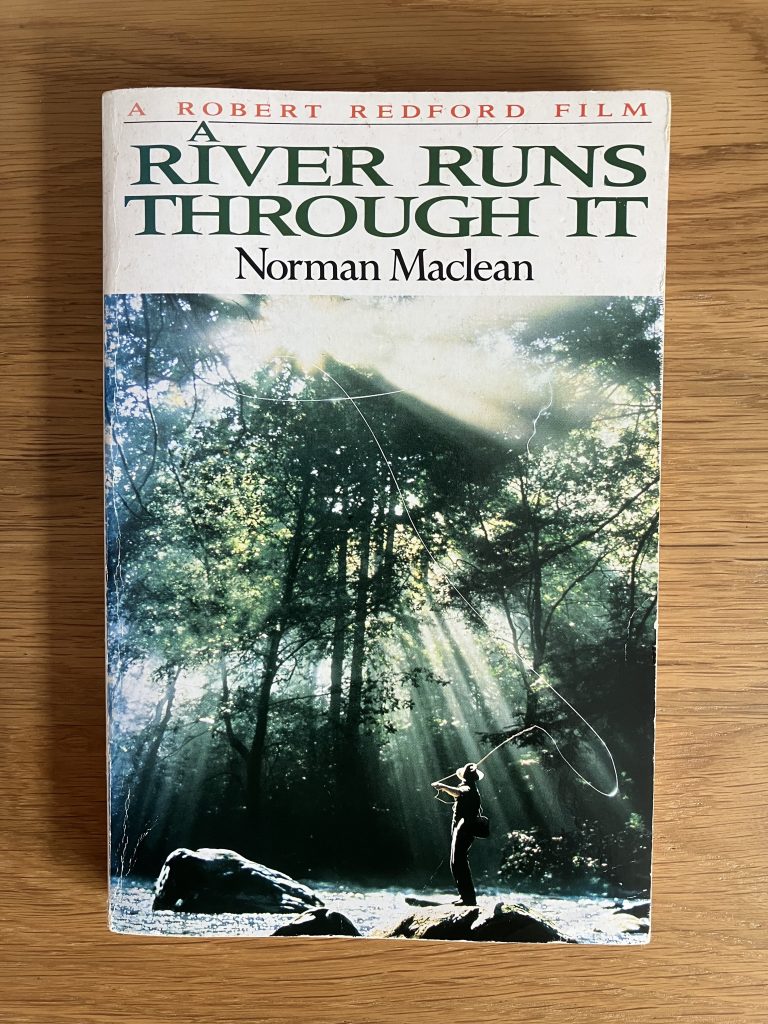

I wondered how she’d react on seeing me bait a hook, after forcing a limpet from its shell with my thumb or pulling a live slater (woodlouse) from a jam jar. I’d squirmed a bit myself the first time I’d seen one of my elders do it. She’d soon get the hang of it. Bait fishing might be a crude practice, but it was a practice I’d learned as a child and could quickly pass on. Unlike fly fishing. Fly fishing, as I was regularly reminded when I picked up Norman Maclean’s A River Runs through It and Other Stories, was “an art that is performed on a four-count rhythm between ten and two o’clock”. I’d tried it only once, in the company of Maclean’s grandson on the Big Blackfoot River in Montana, but I wasn’t (to my shame) ready for it. The sea, with bait or a spinning lure, was the place for me. When I was a kid, when I wasn’t playing football on the Harbour Hill, or browsing in the library, or behind the sofa with a book, I was probably to be found on the rocks…

Nets first, swished in Portmore pools,

Sticklebacks in dread.

Snotty noses press to glass

Over “Golden Shred”.

Next comes hand-line wound on wood,

Orange string for crab.

Nimbler fingers feed it out,

Teasing claws to grab.

On up then to rod and reel

For the pan to strive.

Mannish promises are made:

Glashan, mullet, lythe*.

Years unwind as from a spool

Until sirens call;

Their lures set to landward side

Draw those fishers all.

No more mornings on the rocks,

No guts on the shirt.

Now it’s Kelly’s disco nights,

Swish of Shirley’s skirt.

I’m a lapsed fisherman as well as a lapsed Catholic. I’ve long forgotten the difference between a ledger rig and a paternoster one when it comes to tying hooks. As a child, however, I was taught at primary school to parrot responses in the Latin Mass, in preparation to be an altar boy, so I haven’t forgotten the reminder in “paternoster” of the Lord’s Prayer, and of apostles who were told they would be made fishers of men.

I have picked up a rod occasionally since leaving Portstewart — not because I’ve felt I’ve been missing out but because fishing has offered a way in; a way of writing about places. The first time, in 1996, I was heading for New York, where, as a travel commissioning editor looking after the Americas, I had sent numerous writers. I would be seeing the city for the first time; but how could I see it? It was one of those places where, as Henry James lamented of Venice, “originality of attitude is utterly impossible”. Originality of approach, though, might not be.

* * *

Jon had served his time on the rivers of Montana, and it showed. Watching him cast, watching the sweet flight of line, leader and fly, I was reminded of Norman Maclean’s A River Runs through It, that hymn to the angler as artist. But there was no mistaking our stretch of water for the Big Blackfoot.

Behind us was the slender span of the Verrazano Narrows Bridge. To our right was Brooklyn; to our left Staten Island and, beyond it, Jersey City. Directly ahead, crowded on the water’s edge like commuters on a platform, were the towers of Manhattan. We were angling in New York Harbour.

As soon as I had heard it was possible, I knew I had to try it. Thanks to a ban on commercial harvesting and tighter controls on dumping, there had been a huge increase here in 20 years in the populations of two hungry predators: the bluefish and the striped bass. Both could be caught from a boat. They could be taken nobly, on the fly, or crudely, by the likes of me, with spinner or bait. And if the sport proved disappointing, the sightseeing certainly wouldn’t.

Joe Shastay was my guide to the game fish. A cheery fireman from Jersey City, he worked 24 hours on, 72 off, which left plenty of time for his second occupation of charter-boat captain. Most of his customers were New Yorkers, escaping with him for an evening’s fishing after a long day on Wall Street.

Mine was a daytime trip. I joined Joe and Jon Fisher, aptly named proprietor of a shop called Urban Angler, at 10.15 at a marina on East 23rd Street at the East River. Above us, the Empire State shouldered its way to heaven. Rich men’s toys – El Rancho, Real Escape, Phat Boy – rocked gently at anchor, rigged with only slightly fewer security devices than are found in a New York apartment. “Do Not Board Without Permission,” the notices said. “Alarm Will Sound.”

Joe’s boat, Mako, although more modest in length at 19 feet, lacked nothing in power. We took off at a fair lick down the river. “There’s a 90 per cent chance these fish are running. That’s why I’m pushing it,” said Joe. “We’ve got about a nine-mile run and it’s against the tide.” That, at least, is what he seems to have said. Notes taken against the tide are as hard to read as they are to write.

As the boat hurtled along, I stopped worrying about being sick and tried to stop a silly grin spreading across my face. Two days earlier I had crossed the harbour by ferry, a great hulking craft on which I had seen nothing – it was misty – and felt nothing. Now I was not so much on the water but in it, wind-beaten and bouncing with every bump.

I was on a cushioned seat with my back to the wheel. Jon was sprawled on the bottom of the boat sorting his tackle. Joe turned his head momentarily to the side and gestured to me. “Over there…” he began.

But he didn’t finish. The boat took off, and Jon with it, then came down with a mighty thump. There was a scream, an oath, an apology – and the sightseeing was curtailed. (Joe had been trying to draw my attention to the Domino factory on the quay, where a giant pair of claws was lifting the sugar that would later sweeten New York’s coffee.)

If the logs don’t catch you here, the wakes will. Our buffeting came, I think, somewhere near the Queensboro Bridge. Our passage thereafter, although no less exhilarating, was smoother: under the Williamsburg Bridge, the Manhattan Bridge, the Brooklyn Bridge, past the historic district of South Street Seaport and the unmistakable twin towers of the World Trade Centre (which would be destroyed in the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001). Then, under the watchful eye of the Coastguard and the welcoming arm of Liberty, we swept into the Upper Bay. As we anchored north-east of the Verrazano Narrows Bridge (“suspended out over the Narrows,” as the poet Stephen Dunn put it, “by a logic linked to faith”), Jon was still nursing his tail bone but strong enough to crack a joke. “Since when,” he asked, “has fishing been a contact sport?”

As he and Joe began to discuss tactics – “I’ve got this super-fast-sinking line. How about a little bunker pattern?” – I took in the view. The sky, which had been grey when we left, was clearing, the sun sparkling on the water. I felt sorry for all those suits in their Manhattan offices, all those slaves scurrying between the canyons. We, said a madly macho little voice in my head, are the only livin’ boys in New York.

“You wanna fish?” asked Joe. I did. I started with a spinning rod, following Joe’s advice to cast and then let the line run deep – the fish were feeding near the bottom – while I counted to 20 before reeling in. “Count slow – a thousand and one, a thousand and two… Some people say Mississippi, but thousands work fine for me.”

But not for me. Perhaps the fish had heard my question about tackle and Joe’s answer and knew that what was whizzing through the water ahead of them was “a one-ounce jig with a rubber tail”. Still, it was only just after 11 o’clock. I had more than three hours in which to get lucky.

Joe had other ideas. He told me he had been “skunked” only once in 450 trips; he was determined to see me land a fish, and sooner rather than later. Taking a short boat rod, he baited the hook with a four-inch chunk of oozing fish guts, let the line drop to the bottom over the stern and then handed me the rod. I kept it there a moment, then jiggled to check I hadn’t had a bite. “You don’t need to do that,” said Joe. “Don’t worry – when these fish bite you won’t mistake it for anything else.”

On cue, the rod arched sharply. Having not fished for years, and having become a little squeamish about the whole business, I had wondered what I would think when this moment came. I didn’t think at all. I whipped up the rod, bracing the butt against my hip and reeled as fast as I could, trying all the while to keep my balance in the rocking boat. If I lost the fish, I would be disappointed; but if I dropped the rod or fell in, I would be disgraced.

I didn’t play the fish; I wrenched it in. The landing was a blur: a flash of blue-green, a white belly, Jon (or was it Joe?) bending with the net. Then the bluefish, a couple of feet long, was thrashing inside the boat.

There was a dribble of blood on the second knuckle of my right hand. “Hey,” said Jon, “is that yours or the fish’s?” Mine. In my excitement, I had scraped my finger on the edge of the reel.

I watched as Jon gingerly unhooked the fish. Bluefish will eat whatever is put in front of them, including fish of their own species and fingers trying to free them. The triangular teeth snapped but missed. Jon had suffered enough today.

As the fish went back, I asked Joe whether, if I had kept it, it would have been safe to eat. Yes, he said, but the official advice was to eat no more than one a week. This was not because the harbour waters were dirty but because these were coastal fish, and coastal waters generally were in a bad way.

Within 10 minutes I had landed another bluefish, 28 inches long (we measured it) and weighing perhaps five or six pounds. I remained proud of this even when Joe told me that the boat’s biggest bluefish weighed 16½lb and was caught, with a little help, by an 11-year-old girl. I was proud, too, of my two-foot bass (boat record: 43 inches). It was a beautiful fish, its stripes little diamonds of gold stitched together with black dots. I did feel a twinge of guilt, but less at the catching than the manner of it. Such a fish deserved to be taken on a fly – which is how Joe caught the biggest of our half-dozen bluefish of the day – 34 inches and more than 10lb.

How he found time to do this I don’t know, for he seemed to be everywhere at once: coaching me in the rudiments, advising Jon on the finer points, fetching mineral water, taking the wheel to move us back into “the zone” when tide and current pulled us away. Sheltered though it may be, New York Harbour is no millpond; it’s full of traps for the unwary. Joe, warier than most, told me he still got through six propellers a year.

The harbour was, however, surprisingly free of both noxious smells and noise. We could hear only the slap of water against our boat, the screech of gulls and the sound of metal somewhere being hammered on metal.

Traffic was light. Now and again a rusting barge loaded with containers would slide between us and Manhattan, like some hobos’ train that had taken to the water. A top-heavy sport fishing boat, swaggering home, would smack us with its wake. And once, out of the corner of my eye, I glimpsed the orange bulk of the Staten Island ferry making its famous and famously cheap circuit.

Norman Maclean, I remember thinking, would have been appalled at the notion of fishing in such a setting. I loved it.

* * *

I first came across Maclean’s writing in 1990 (the year he died, aged 87). I was editing the “Outdoors” pages of the Saturday Telegraph, and our fishing columnist, the novelist David Profumo, had written the introduction to the British edition of A River Runs through It (which had first appeared in the US in 1976). “Readers who make a habit of pressing books on other people can be a tedious race,” he wrote, “but I’m going to take my chances… A River Runs through It has become one of my favourite works of modern literature. I only wish I had written it myself.” I was similarly smitten; 15 years on, I got a chance to make a pilgrimage to Norman Maclean’s backyard.

* * *

The barman at Bayern Brewing hadn’t been expecting us, though his T-shirt suggested otherwise. On the front was an image of a cutthroat trout and the logo “WestSlope Chapter Trout Unlimited”. On the back, in black lettering against grey, were these words: “The world is full of bastards, the number increasing rapidly the farther one gets from Missoula, Montana.”

It was July 2015, a festival dedicated to Norman Maclean and his work was about to open, and two of us had come to collect a couple of kegs, donated by the brewery’s boss, to help lubricate the literary gathering. After all, “in Montana drinking beer does not count as drinking”.

Both that line and the one about bastards are from the title piece of A River Runs through It, a three-story collection that runs to only 217 pages in my well-thumbed Picador paperback edition but has something quotable on nearly every page. On opening it, I was transported from the suburban sprawl of south London to the big skies of the Rockies. Its lead story, one of fly fishing and familial love, and of the impossibility of being your brother’s keeper when your brother is bent on self-destruction, was sensitively adapted by Robert Redford in a film, released in 1992, that made a star of Brad Pitt. (The making of the film was explored in the second “Maclean Footsteps Festival”, held in Montana in September 2017.)

The book’s other two stories drew on Maclean’s experience in his youth in a logging camp and as a firefighter with the US Forest Service. They were stories of the west, suffused with the rhythms of poets Maclean had lectured on further east. “I think poets have influenced me more than prose writers,” he told one interviewer, citing Wordsworth, Hopkins, Browning and Robert Frost, with whom he had taken a writing seminar while earning his BA at Dartmouth College. In 1922 he had entered the poetry competition of The Dial magazine in New York, which was won by TS Eliot. The judges weren’t unanimous: two chose “The Waste Land”, but one, Carl Sandburg (the man who made Chicago the “City of the Big Shoulders”), preferred a poem from Maclean.

He published only two books and a few essays. This was partly because he didn’t get going as an author until he reached his “threescore years and 10”, after a distinguished career as a literature professor at the University of Chicago; it was partly, too, because of a Presbyterian perfectionism instilled by his father, a Scot and a Presbyterian minister, whose idea of home-schooling was to set his son a composition, then order him to cut it by half and by half again. Maclean died in 1990, without seeing Redford’s film and before finishing a second book, about a forest fire that had killed 13 of 16 firefighters in Mann Gulch, Montana, in 1949. It was published, as Young Men and Fire, in 1992.

Until 2015, I had read only an excerpt from Young Men and Fire, but I had read A River Runs through It four or five times, and raved about it to other readers. I had recommended it, too, to would-be writers, partly for the lessons it offers in making every word count. As soon as I heard of plans for the first “Maclean Footsteps” festival, at Seeley Lake, where the writer’s family has long had a summer cabin, I booked my place. But first I flew in to Missoula (pronounced “Mizzoula”), between Glacier National Park and Yellowstone Park, where the story started.

Norman Maclean was born in 1902 in Clarinda, Iowa, but moved in his sixth year with his family to Missoula, where his father, John, had been appointed pastor at the First Presbyterian Church. It was then a timber town where cowboys were “ranch hands” and “Indians” still pitched teepees in summer along the Clark Fork River. These days the cowboys are outnumbered by hippies (Missoula, home to the University of Montana, has a reputation as the state’s most liberal town) and the banks of the Clark Fork are lined by kayakers awaiting their turn on an artificial wave.

The church the Reverend Maclean first preached at is gone, replaced by a towering building in red brick. Outside is a grey stone plaque etched with an image of a fisherman up to his knees in a river, mountains rising behind. The inscription says: “In memory of Dr John Norman Maclean, pastor of First Presbyterian Church from 1909 to 1925, whose love of God, family and creation inspired the story ‘A River Runs through It…’.” That story, a fictionalised memoir, tells how the Reverend Maclean made anglers of his sons (“In our family, there was no clear line between religion and fly fishing”), and how the younger one, Paul, an artist on the river but a gambler and street-fighter in town, came to a bad end at the age of 33: beaten to death in an alley with the butt of a revolver.

Paul is buried with his parents in Missoula cemetery under a simple two-tier stone. Sprinklers played in high arches over the grass as I walked along the rows to see it, under a Montana sky that was as big as I had expected, but hazier. Mary Holmes of Destination Missoula put me right: it wasn’t haze; it was smoke from forest fires in Idaho.

We heard more about those at the Smokejumper Visitor Centre, on the edge of town. Smokejumpers are parachuted into remote areas to suppress small fires started by lightning and fight more extensive ones. Of the 65 based in Missoula, 60 were out on jobs, some as far away as California. We saw the tools of their trade, the manufacturing room where they sew their own suits and harnesses, the tower where their chutes hang, and the lockers or, rather, cages, where, when they get a call, they drop everything that’s not essential to firefighting: backpacks, house keys, family snapshots.

One room, a mock-up of a fire lookout tower, had a bed that Norman Maclean would collapse on to after a day’s writing in the cabin at Seeley Lake. A caption signed by his son, John (also a writer), pointed out that it had no box spring, so cold air came straight into it. “Maclean at first put a layer of newspapers under the mattress. It didn’t help much — the cabin is heated by a single stove — and eventually he added an electric blanket. The bed was donated to the Missoula Smokejumpers, memorialised in Maclean’s Young Men and Fire,… when it was finally replaced, in 2005.”

Michael Cropper, whom I’d helped to pick up the beer kegs, drove me the 50 miles or so to Seeley Lake, alongside dense forests, high mountains and a chain of glacial lakes. En route, we passed the high-rise accommodation of some regular fishing tourists: ospreys, up from Mexico to nest on poles in the Seeley-Swan Valley.

Michael, a sprightly Englishman in his eighties, and his partner, Sara Wilcox, who met on a sailing trip, sold their boat and built a cabin on a hill overlooking Seeley Lake. It’s a little town (population: 1,659) but a literate one: Sara, who ran its book club, said a talk by a writer could draw close to 100 people in the winter. The festival was her idea, and she roped in as co-ordinator her friend Jenny Rohrer, who, being a film-maker, knew how to raise funds. Between them, they signed up as speakers members of Maclean’s family, academics and editors, the novelist Pete Dexter — author of Paris Trout — and the governor of Montana, Steve Bullock.

Dexter had written a profile of Maclean for Esquire magazine in 1981. He told the gathering: “I was just really starting to be a writer at that point and I’d read A River Runs through It and wanted to be the guy that wrote that. I still do… I wasn’t copying Norman’s words or anything, but I was trying to compete — not to be him, just so he would like me.”

“Part of the power of Norman Maclean,” the governor said, “is that he reminded us that place is important, not just in a practical way but in a deeply grounding and often magical way. For those of us who call Montana home, the landscape is as much a part of our identity as is our family, our profession or our faith.” He touched, too, on the inspiration Maclean had given both conservationists and writers, and the contribution A River Runs through It had made and was making to tourism. Montana, a state of a million people, drew 11 million visitors a year, who added $4 billion to its economy. He said it was hard to quantify Maclean’s role in that, but he noted that what he called the fly-fishing “industry” grew by 60 per cent the year the film came out, and by another 60 per cent the following year.

Maclean wouldn’t necessarily have seen that as a blessing. In a letter in 1976, he complained of the Big Blackfoot river: “…there are so damn many fishermen on it now you have to bring your own rock with you”.

The festival bill included walks as well as talks. Heading off on an outing to some of Maclean’s favourite fishing holes, we filled a yellow school bus, and I was reminded of John Steinbeck’s warning that “two or more people disturb the ecologic complex of an area”. If we were a crowd, we were a respectful one, intent on on-the-spot readings from A River… by our guide, Jerry O’Connell, and occasional contributions from Noah Scot Snyder, Maclean’s 40-year-old grandson.

Jerry, a fly fisherman since childhood, is founder of the Big Blackfoot Riverkeeper, which aims to save the river from “being loved to death”. He fell for the Blackfoot Valley while hitch-hiking through Montana in 1986 and moved there from New England six years later. He has engraved on his wedding ring the penultimate line of “A River Runs through It” (“Under the rocks are the words, and some of the words are theirs”, with “theirs” changed to “ours”), but he hasn’t gone quite so far as a fisherman he knows in Sweden, who has tattooed on his back, in gothic lettering, the final line: “I am haunted by waters.”

Noah, a producer, mixer and engineer of film scores and albums (he won a Grammy in 2003 for his work with the singer-songwriter Warren Zevon), is now based in Los Angeles but escapes when he can to Montana. Our final stop was one where he remembered being taken by his grandfather. Places mingled in his memory, he said, but he was sure of this one, partly because of a distinctive layering of rocks, like stacked slates, a few yards from shore.

In readiness for the festival, I’d been briefing myself with the excellent The Norman Maclean Reader, edited by O Alan Weltzien, who was one of the speakers over the weekend. In a letter Weltzien includes, Maclean tells how his written stories emerged from the ones he used to tell his children and his western pals: “Even your children or your pals aren’t going to listen to you for more than 10 or 15 minutes, so there is great premium on deletion, and especially of all scenery. Besides, they know the scenery. All you have to say is ‘the Blackfoot river’.”

How, then, did Maclean manage to carry me, and so many others who had yet to see that scenery, all the way to Montana? I’m reminded of advice a writer friend of mine was given by the great London publisher Jock Murray: “Cut, and an echo of what you have cut will remain.”

In “A River Runs through It”, Maclean tells how his father instructed him to cast on a four-count rhythm, sounded out by a metronome. Noah had it easier. He was allowed initially to use a spinning rod rather than a fly rod, but there had to be a lure on the line. “Even if we were going to break this sacrament of fly fishing we still had to observe certain rules. We couldn’t use bait — that was not gonna happen.”

Noah is now an accomplished fly fisherman, as I saw next day when Jerry took both of us out in an inflatable on the river. At our starting point at Corrick’s River Bend, the Big Blackfoot was a tricolour landscape: rounded grey stones on the shore, grey-green willows above them, and then, arrowing darkly heavenwards, forests of pine, fir and western larch. Within 15 minutes, Noah had hooked the first of a series of tiddlers, among them a cutthroat and a brown trout. “I’m only catching fish that haven’t been around long enough to know the difference between a real bug and a man-made one,” he joked.

A couple of hours in, he got another bite, a bigger fish. Jerry nodded approvingly as Noah reeled in: “That’s a hell of a nice fish — a 16-inch cuttie.” Just as Noah was about to take it from the water, though, it slipped off the hook. While Noah cast, Jerry educated and entertained (“I can get a fly tied in a minute — but it does end up looking like a love-seat shot with a goose gun”). He filled me in on the way in which the river was being damaged by logging, mining and grazing before Redford’s film — so much so that most footage of fishing was shot elsewhere in Montana. Since then, the Nature Conservancy, working with local groups, had bought up land in a series of parcels, most recently adding a ridgeline that was one of the finest habitats for wolverine and grizzly bears in the United States. “So we’re now surrounded by protected land. It’s phenomenal.”

I’d told them I’d only ever fished with spinners or bait, so Jerry reckoned it was “time to get that fly-fishing virginity smell off you”. My first cast, predictably, fell in front of me. The Compleat Tangler. When I tried again, the line barely lifted off the water. Jerry spotted the problem: the rod had snapped a couple of feet from the tip. It was nothing I’d done, he said; there might have been a weakness there, something waiting to go, and the rod was under lifetime guarantee. Still, I felt guilty, and I had nothing to fish with.

There were compensations: beaver dams, a mink scurrying through the bankside brush, and the call of what Jerry told me was a bald eagle. For such a powerful bird it was surprisingly dainty: a series of high-pitched piping notes. That’s why film-makers were in the habit of overdubbing it with the more muscular cry of the red-tailed hawk.

I could understand what had made Jerry up sticks from New England. I could understand, too, why Norman Maclean, who decided he couldn’t live in Montana if he was to fulfil his potential as a teacher, had found his wellspring there as a writer.

* Glashan is a local name on the Causeway Coast for the coalfish, and lythe is a local name for the pollock.

Norman Maclean: A Life of Letters and Rivers by Rebecca McCarthy was published in 2024 (University of Washington Press); I can thoroughly recommend it.

Leave a Reply