Saturday and Sunday mornings in our house are for lingering over newspapers. Pre-pandemic, I’d just have spread them on the kitchen table, but that’s in shadow, so now I take them to the table in the living room, in front of the french doors. I want natural light, and I want to be able to raise my eyes occasionally from print to garden. The goldfinches seem to know when I’ve reached the financial pages and would welcome a break.

They weren’t among our regular visitors until recently. Teri was told by a friend that they’re particularly partial to the black oily seed of the niger, Guizotia abyssinica, a plant with a yellow flower that’s native to the highlands of Ethiopia. So it has proved. One of the feeders dangling from our gnarled old pear tree is now filled with niger seed; we regularly see two or three goldfinches at a time tucking into it and another half dozen whirring and chirping round about them. When they’d had their fill one Saturday towards the end of November, and headed on, I turned back to the City pages of The Guardian.

I was drawn in by two images of San Francisco. The first was in three planes: in the foreground were young people enjoying a sandwich and a coffee on the grass in Alamo Square park; behind them were the “Painted Ladies”, those Victorian mansions that were built with Gold Rush profits at the end of the 19th century and survived the earthquake that followed; and beyond them were the Transamerica Pyramid and the other sky-piercing towers. The second, smaller, picture showed tents on tarmac in front of City Hall: as the caption put it, “the officially sanctioned encampment for homeless people”.

The accompanying story by Rupert Neate (‘Wealth correspondent”) told how Matt Haney, a member of the city’s legislative body, had tired of walking to work at city hall and seeing, on the one hand, the luxurious homes of tech billionaires and, on the other, hundreds of the country’s most desperate people living in tents on the street. His answer: a new “overpaid-executive tax”. An extra 0.1 per cent tax would be levied on companies that paid their chief executive more than 100 times the average wage of the staff. It was estimated that the tax* would bring in between $60 million and $140 million a year.

Haney said he hoped the approach would serve as an example to others: “San Francisco is a modern-day Tale of Two Cities everywhere you look; we can’t have a nation that turns into that.”

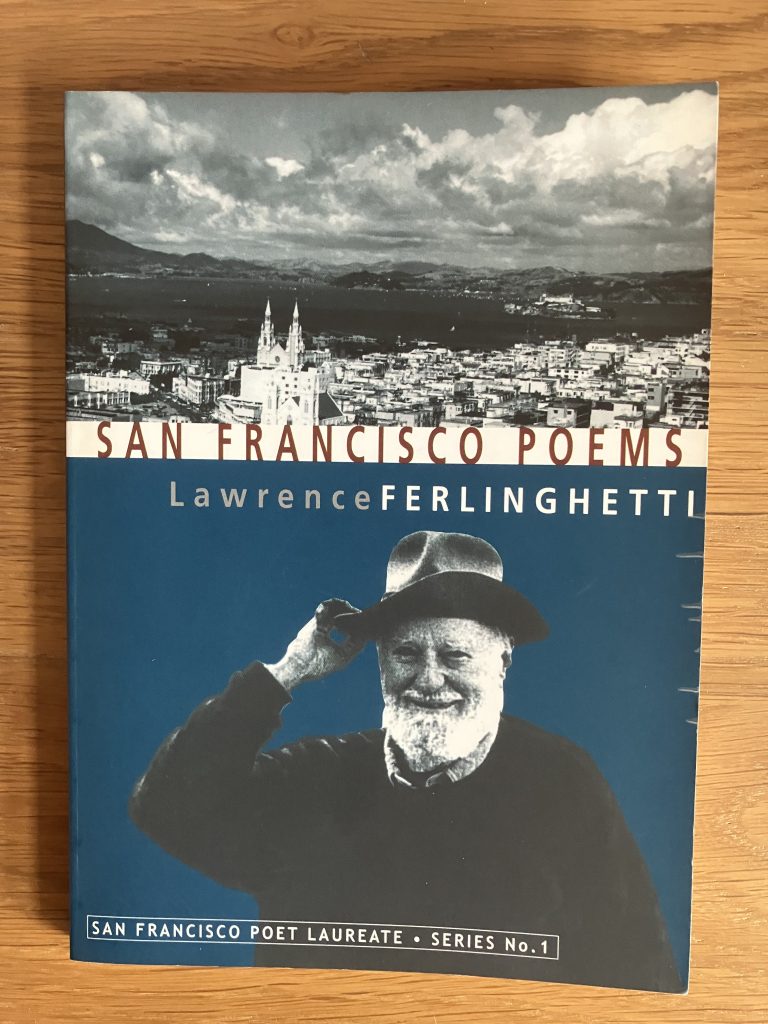

Which reminds me of a line in Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s San Francisco Poems (published in 2001). To double-check it, I look for my copy among the books in the front room. In a prose piece, “The Poetic City That Was”, Ferlinghetti tells how, 50 years after settling in San Francisco, he found himself priced out of his old flat and his studio. Many of his friends were also evicted, “for it seemed their buildings weren’t owned by San Franciscans any more but by faceless investors with venture capital”. The great divide that Matt Haney hopes to bridge has been deepened by the pandemic, but it has been there for a while; it was already striking during my second visit to the city, in 2002.

* * *

In the leafy graveyard next to Mission Dolores, remnant of the Spanish Empire and the oldest intact building in San Francisco (it dates from 1785), there lies a curious collection of individuals. Among them are Noes, Sanchezes and Castros, people who have given their names to streets and to whole districts of this city. Among them, too, is one James Sullivan, a native of Bandon, Ireland, who “died by the hands of the VC, May 31st, 1856, aged 45 years”.

I was puzzling over this inscription when a grey-haired docent — a volunteer guide — appeared at my elbow.

“Mr Sullivan was hung for stuffing ballot boxes,” she said.

Really?

“Uhuh.” And VC, she explained, stood for Vigilance Committee (a group of vigilantes set up by local businessmen who argued that crime and corruption had got out of hand). “It might have been a bum rap, of course. We had no lawyers in those days.” Hands on plump hips, she grinned at me. “Imagine it: California without lawyers.”

Impossible. It would be like San Francisco without the fog; the fog which, in summer if not in fall, is a constant. This was the forecast on the back of the Chronicle the morning after I arrived: “Today: Coastal fog early, then mostly sunny. Sunday: Areas of morning fog… Monday: Areas of morning fog…”

But the San Francisco fog is nothing like the old London pea-souper that cloaked the killings of Jack the Ripper. That was a curse, and this is a blessing. It advances from the ocean in weird and wonderful shapes, bringing with it the clean, salty tang of the Pacific, keeping a lid on the temperature, and ensuring that, however far you walk (and in this city you’ll want to go a long way), you never get hot and bothered.

Fog is good. Fog is fun. Fog is a marketing opportunity. There’s a Fog City Diner, a Fog City Cat Club, even a woman’s Gaelic football team called the Fog City Harps.

But fog is only the most distinctive feature of a thoroughly strange climate. As you move from one neighbourhood to another, you find yourself first under cloud, then under a flawless blue sky; first feeling the sun on your arms, then rolling down your sleeves against a chill. If it doesn’t feel good where you’ve stopped, all you have to do is walk a few blocks. Think about it: this is a place where you can control the weather.

If the practice of magic isn’t enough, and you want to study theory, you can do that, too. Many of the bookshops stock a little guide, Harold Gilliam’s Weather of the San Francisco Bay Region, which crisply (and occasionally lyrically) makes the whole system clear.

I bought mine — and, of course, my copy of San Francisco Poems — in City Lights, which Lawrence Ferlinghetti started in 1953, not just as a bookshop but as a publisher. Its most celebrated title was Allen Ginsberg’s poem “Howl”, which Ferlinghetti and his manager successfully defended in court against charges of obscenity. It was a famous victory in the war against censorship.

The shop, with its black and red floor tiles and its handwritten shelf labels — “Anarchism”, “Class War”, “Muckrakers” — was still thoroughly right-on (though there was something dispiriting about that notice saying bags must be left by the door). Its proprietor, judging from his writing, seemed to have matured from an angry young man into an angrier older one.** San Francisco Poems includes the address he delivered on his appointment in 1998 as Poet Laureate of this “far-out city on the left side of the world”. In it he has pops at car culture, at chain stores, at tourism and at “militarism”. He laments, too, “the gap between the rich and the poor in San Francisco”.

That gap was one of the first things I noticed. I had seen a few homeless people on my first trip to the city in 1996.Now they seemed to be everywhere in the centre: drinking from brown bags near a cable-car terminus, sleeping a door or two from the smart hotels, begging or busking at the corners. In any other American city this would have been something the tourist trade avoided mentioning. Here, the hotel association had booked billboards to draw attention to it. One showed a businessman holding up a scrap of cardboard on which was written this question: “I want to know why homelessness is still a problem after we spent $200 million last year.”

A more subtle commentary seemed to be implicit in an exhibition at the Palace of the Legion of Honour, a neo-classical building wonderfully situated in a park above the Golden Gate. On show was the work of the Flemish painter Michiel Sweerts, and the centrepiece was The Seven Acts of Mercy, a series he painted after the worst crop failures of the 17th century. In these dark pictures, their central figures theatrically spotlit, a few well-dressed, well-meaning men went about the streets of Rome, Feeding the Hungry and Refreshing the Thirsty.

Coincidence? Maybe. But remember: it’s as sinful to be lacking compassion in this city as it is to be un-American in Kansas. The timing of the billboard campaign was certainly no accident. It was designed to embarrass the city authorities, who were planning that very week to reopen the landmark plaza Union Square after a $25 million renovation. “Union Square,” the mayor, Willie Brown, had declared earlier, “is the heart and soul of San Francisco… It’s the urban magnet that draws people to this great City by the Bay.”

Is it? I don’t think so. Union Square is a shopping district, and no one goes to San Francisco primarily for its shops. The square is no more of a must than Fisherman’s Wharf, which you should set foot in only if you can’t survive without one of the following: a cartoon-convict nightshirt saying “Alcatraz Reject — Too Cute”; a wedding ring “made with a portion of gold from a sunken ship”; or an emergency earthquake kit, “with food, water, first-aid supplies, blankets, portable commode”.

No, you come to San Francisco to sip coffee in North Beach, to eat in some great restaurants, to giggle at the pretension of Yoko Ono in the Museum of Modern Art, and to walk street after street, working your calves on those famously steep hills. You come, too, to ride America’s only mobile National Historic Landmark: the cable car.

It’s best to go early in the morning or late in the evening to avoid your fellow tourists. And stand on the running board. In a state obsessed with health and safety (where even the Irish coffee comes in a decaffeinated version), this is a rare chance to do something that is potentially dangerous but perfectly legal.

After a meal and a few drinks, I caught the Powell-Hyde car near its start at Market Street all the way to Fisherman’s Wharf. As the car lurched upward I heard the metallic clink of wheel on rail, the whirr of the cable beneath the street, the crisp clang of the bell. I smelt oil and burning wood.

“Smells to me like a barbecue,” our “grip man” said. He was as good as a play, teasing and entertaining the passengers, giving some well-worn quips a topical spin. “Lombard Street,” he shouted as we approached it. “Crookedest street in the world. But not as crooked as our economy…”

After that, the BART (Bay Area Rapid Transit), with its automated announcements, was something of a letdown, but it did get me across the water to the leafy campus of the University of California, Berkeley. When you see people lying on the ground here, you can be pretty sure they’re not homeless; they’re just taking a break from swotting for Nobel Prizes.***

There were beggars, outside the T-shirt shops on Telegraph Hill, but they were younger and their needs less urgent than those of the people at Union Square. They didn’t ask you to spare some change; they pointed lazily to notices asking you to “Spare Some Change For Dope”. But that, it seemed, was as far as Berkeley’s anti-authoritarianism now went. In the 1960s and ’70s the place had been synonymous with marches over civil rights and free speech and protests over the Vietnam War that were often met by police in full riot gear. When I stopped for lunch, I found, sitting comfortably among the students, heavy boots tapping to Van Morrison, a couple of cops.

Not quite what I understood by counter-culture. But then the Beats were long gone. The Grateful Dead were dead (or at least their leader was, and commemorated by, of all things, a Ben and Jerry ice cream called the Cherry Garcia). The Castro district was now so thoroughly accepted as the gay part of town that it hardly needed to assert itself.

These days, indeed, the only way to strike an alternative posture in San Francisco was to be straight. And nowhere seemed straighter than the Marina district, in the city’s north-west corner, where the bars at night were full of boys on the look-out and girls on the pull and pick-ups were made even in the aisles of Safeway’s. In the Buchanan Grill, an old-fashioned neighbourhood bar and restaurant, I found the gents’ tellingly plastered with girls in swimsuits from the pages of Sports Illustrated.

Cecil, I reckon, would have approved. We met in John’s Grill in Ellis Street, back in the centre of town. I was there because I was reading Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon, and it was in John’s Grill that Hammett’s private eye, Sam Spade, having been hoodwinked by his client Brigid O’Shaughnessy, went to eat while deciding his next move. Cecil was there — in a tux — because he was playing jazz over the road and needed a breather and a bourbon.

Cecil, who was what the locals would call a senior, had a joke for the bartender and a smile for every woman in the place. We got talking, and he told me that he thought political correctness in his city had gone too far: “It’s got so a guy can’t look at a girl without being hit by a lawsuit.”

We talked about the homeless, too, some of whom he found frightening. A night or two earlier, he said, he had been chased by a beggar and had to jump in a cab to escape.

But the homeless I encountered were far from scary. One man, playing a collection of upturned buckets, was a hugely talented drummer. An old woman, to whom I gave a couple of bucks for coffee, promptly passed it on to someone she reckoned was in worse shape than herself.

Threatening? Hardly. I was the only one who was a threat during my stay. Or so I must have seemed to the two soldiers in the Humvee by the Golden Gate Bridge (which, since 9/11, had come to be seen as a potential target).

I snapped a couple of pictures. Then a couple more. At that point the hand of one of the soldiers went up flat against the Humvee’s windscreen and he stepped out, fingering his rifle. “Sir,” he said, “we don’t mind a few pictures, but you got enough there for a reconnaissance.” In this famously liberal city, I had bumped up against the limits of tolerance.

* * *

There are times when, however highly they esteem the philosophy of Otis Redding, even San Franciscans can tire of sittin’ on the dock of the bay. When that mood takes them, they head north to the mountains and forests of Marin County, to bike, hike, climb or, at the very least, hug a redwood. They drive there, cycle, take a ferry or, as I did, they walk across the Golden Gate Bridge.

It was a Sunday, with the US Fleet in the city and fighter pilots showing off in the sky. (Ferlinghetti wouldn’t have been impressed: to him such acrobatics were “a frightening militarist and nationalist display of pure male testosterone”.) Traffic crawled along under the eyes of good-humoured cops on mountain bikes. More mountain bikes whizzed past me as I walked a dusty trail through the Presidio Park and on to the bridge.

I had seen all the pictures, read all the hype; all the guff about Joseph B Strauss being both engineer and poet. Now here it was, his Golden Gate Bridge. It was as bold and masculine, as graceful and feminine, as I had been led to expect. But it was an awfully long way above the water, and I’m not fond of heights…

I set off, looking dead ahead, keeping to the side of the walkway that was nearer to the traffic and thus farther from the edge. The fog that had been cotton wool at a distance was thicker close to hand, so that 50 yards ahead the bridge, like some stairway in a dream, faded to one rust-red stanchion without top or bottom.

It was hard to forget that the bridge would soon turn 60and what happens to joints at that age. I headed for the stanchion, all the while reciting a litany of reassurance: 670 cubic yards of concrete, a million tons of steel, the capacity to carry the weight of 10,000 cars an hour. What views there were through that famous fog were lost on me. I walked the mile or so without once peeping over the edge, without once looking back, although I couldn’t help seeing, at intervals, the emergency phones for the suicidal.

Then, as abruptly as though a curtain had been pulled, the fog was gone, and there were the headlands of Marin County, bathed in sunshine, and yet another squadron of lean, Lycra-clad mountain-bikers. “Which way to Sausalito?” I asked one of them. He told me. Then, looking me up and down like some medic appraising a coronary case, he added: “It’s a long way. Allow yourself an hour, an hour-and-a-half.” Forty-five minutes later, having paused for a look at Fort Baker — more a small town by Rockwell than an army base — I was there.

Even when translated from the Spanish, Sausalito is a lovely name: the place of the little willows. The town is only half an hour from San Francisco, and suffers a little from this proximity. Once full of bordellos and gangsters running rum, it’s now full of galleries and tourists buying deck shoes. But it is undeniably beautiful, especially in the evening, when the houses climbing its wooded hills glow like so many fireflies.

Having returned with my bags and spent a couple of nights there, I can vouch, too, for its appeal in the morning. I took my lead from Otis Redding, who began writing “Dock of the Bay” while staying in the summer of 1967 on a houseboat in Sausalito, his base during a week of concerts at a club in San Francisco.

I sat on the deck outside my hotel bedroom as a weak sun began to rise. A kayaker slipped soundlessly past. A heron flapped from the ferry quay. Across the bay the fog peeled from the city, revealing the sharp pyramid of the TransAmerica Building and, under the Bay Bridge, as if it were a central support, the gloomy hump of the former federal prison of Alcatraz.

Sausalito itself is beyond the fog belt, which is one reason why so many city people move there, the most prosperous building houses high above where they moor their boats. At the start of the 20th century, the folks on the hill were at odds with the folks on the flat. The former wanted the civic framework that would bring drains and sewers and fire engines; the latter wanted to keep their low taxes and freedom. Urbanism, as ever, triumphed.

A few bohemians remained, living on houseboats to the north of town. Some had been there since the 1950s, holding out against those who would sweep them away in favour of another marina. I searched for these boat people, approaching their haunts — a timber Taj Mahal, a gingerbread dwelling out of Hansel and Gretel — with the guile and good intentions of a David Attenborough. But I saw nothing of them. Like all endangered species, they had a strong instinct for self-preservation.

So I moved on up the main street, Broadway Boulevard, to the town’s one organised tourist attraction. It may be a drab-looking shed, but it’s a shed in which time passes faster than anywhere else in California. A day here lasts precisely 14 minutes and 54 seconds. The shed — the Bay Model Visitor Centre — houses a miniature world, the world of the San Francisco Bay and Delta, its 1,600 miles here reduced to 1.5 acres, or about the size of a football field; and as everything is strictly in scale, it is a world shrunken not only physically but temporally.

The model looks like the scene of a war game — it was built by the US Army Corps of Engineers — but no toy soldiers people its grey hills and dips. I looked in vain for the most obvious of San Francisco landmarks: the Golden Gate Bridge, the Bay Bridge, the TransAmerica Building. It is the detail below sea level — the channels, shapes and slopes of river bottoms — that is of greatest interest to the engineers. Their aim is not to delight model-makers but to simulate the tides, currents, river inflows and other variables affecting the bay and delta, which together form the largest estuary on the west coast of the United States. From experiments here they can predict the impact of events in the wider world. What if a shipping channel were deepened here…? What would be the path of the slick if oil spilt there…?

I wasn’t lucky enough to turn up on a day when water was sluicing through the system, but there were plenty of knobs to turn and buttons to push, still sticky from the hands of schoolchildren who were being led around by a jolly ranger in a wheelchair. “What’s the word?” she would cry. “ES-TU-ARY,” they would answer.

To everyone else, of course, the word is bay — or, rather, The Bay, just as San Francisco is The City and Alcatraz is The Rock. However hazy they may be on other matters, San Franciscans are definite about their articles. I had seen enough of Alcatraz on the way across the Atlantic. In the in-flight movie, it had been the base for a band of aggrieved special-forces troops who had threatened to blanket the city in nerve gas and were dispatched just before they could do so by Messrs Connery and Cage. So I took the ferry instead to another former prison, Angel Island.

The island, half an hour from the tourist tat of Fisherman’s Wharf, has also been a military base and an immigration holding centre. It is now a state park. You can ride a bike round its deserted garrisons and gun batteries or hike to the summit at its centre, the 781-foot Mount Livermore. I plumped for a mountain bike, hiring it as soon as the ferry put in at Ayala Cove. The woman behind the counter looked me over to assess me first for bike and then helmet size. “I think this one will do. And this one.” She was right both times. I marvelled at her eye, and even more so when she said: “I don’t normally do this. I’m the catering manager.”

So I forgive her for telling me that once round the first two corners I would find the trail “pretty well flat”. It was nothing of the kind, but it did provide a wonderful 360-degree prospect of the bay. Every twist and turn would reveal a new view: the Bay Bridge, then Alcatraz, then the Golden Gate Bridge, its fog from here so localised that it seemed to owe less to meteorology than to architectural wizardry.

The sky was bright blue, the air minty with the scent of eucalyptus, which the rangers were felling to replace with the original oaks and bays and native grasses. Run-down guardhouses, in a peeling ochre, were spooky even in the sun.

On my first circuit of the five-mile trail I saw only a couple of overloaded hikers, snails bent under their homes. On the second, I met a little bus, carrying a party of “seniors” in their espadrilles and open-toed sandals. I resented the bus’s intrusion, but perhaps it was necessary, for not everyone is up to negotiating the wilds of Marin County single-handed.

One of my fellow mountain-bikers, on arriving at the start of the trail, and with map in hand, asked me: “Where does it go?” Another, on being told by the ranger that the next ferry back to the city was at 2.10pm, went off and told her companion: “Two-twenny. We gotta get the two-twenny.” And a third lost his ferry ticket, which was restored to him by a boy of eight called Tucker, who had been cycling with his mother.

Tucker said: “I found it for you. You owe me 20 bucks.” The ticket had cost $10. Tucker, I reckoned, could safely be allowed back to Angel Island on his own.

* The “overpaid-executive tax” came into force in January 2022.

** Ferlinghetti died in February 2021.

*** Between the 1930s and 2024, Berkeley had 59 Nobel Prize-winning laureates.

Leave a Reply