When Teri and I take a walk in Nonsuch Park, we find snowdrops pushing through dead leaves alongside the path up to the Mansion House. Signs of renewal and recovery next to a building that’s been pressed into service as a vaccination centre. I’m reminded that in 1665, when Nonsuch was the site of a palace, the Exchequer was moved there from Westminster “by reason of the great and dangerous increase of the Plague”.

Back home, dipping again into John Dent’s The Quest for Nonsuch, I learn how, little more than a month on from that move, the Lord Treasurer had “reached a state of exasperation over the dislocation in the work of his department caused by its dispersal. He promulgated rules for the attendance of Officers of the Receipt… They were not to be absent without leave for more than a week. They were to attend to their duties in person, and not to ‘remit all to their clerks as of late hath been done’.” The Lord Treasurer sounds like a boss who feels he’s losing control in the age of Zoom and working-from-home.

Joe Biden, America’s new leader, delivered his inaugural address yesterday (January 20, 2021) in circumstances that were far from normal. Biden, Kamala Harris (the first woman of colour to be named vice-president) and others on stage wore face masks; there were no spectators on the National Mall, which was fenced off after the attack on the Capitol by Trump loyalists that left five people dead; the Capitol Complex was full of National Guards; and the outgoing president failed to show up.

In our house, thanks to our role in a “childcare bubble”, Biden had to compete with two small children coming to blows over a Monopoly board. It was no contest. I gave up, watched highlights of the inauguration later on Channel 4 News, and then looked up the full text of Biden’s speech online. I’d wondered whether his forefathers would be mentioned. They weren’t — but then he did have a few other things on his mind:

“We face an attack on our democracy and on truth, a raging virus, growing inequity, the sting of systemic racism, a climate in crisis… Any one of these will be enough to challenge us in profound ways. But the fact is, we face them all at once, presenting this nation with one of the gravest responsibilities we’ve had. Now we’re going to be tested. Are we going to step up?”

I reckoned he could probably count on the Irish. His ancestors emigrated from Louth and Mayo in the middle of the 19th century, and throughout his life, he has said, he has been mindful of the words of his grandmother: “Remember, Joey Biden, the best drop of blood in you is Irish.”

If my mother were still with us, she would be reminding me, lapsed as I am, that Biden is not only Irish but “from our side of the house” — a Catholic.

As a small boy in the north of Ireland, I looked up to John F Kennedy. His film-star face, in its gilt frame, shared space on our kitchen walls with the Pope and the Sacred Heart. I took in its implicit message along with my morning porridge: here was a fella from Irish Catholic stock who had made good, and I could make good too. In the years since, I’ve learnt more about the man and his family, not all of it to their credit. Reading, and the scepticism my trade teaches, have dispelled the image I had of Kennedy as a boy, but they haven’t dislodged my understanding of what he meant for my parents.

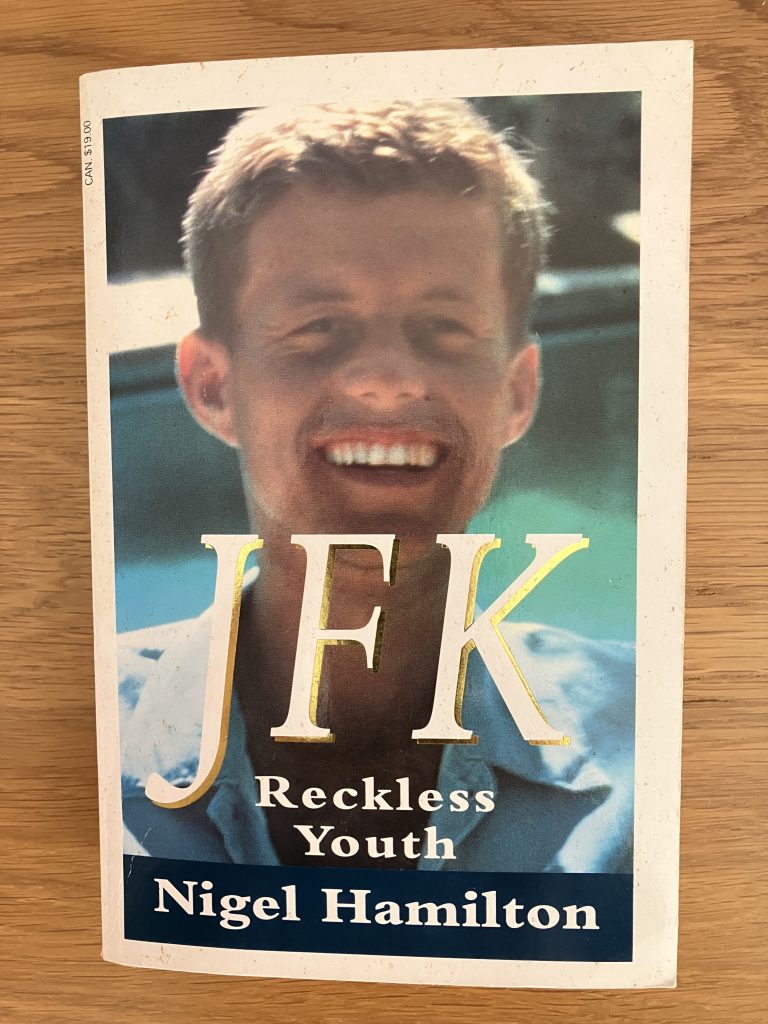

On my first trip to Boston, then, in 1999, my priorities were not those of a typical tourist in America’s most historic city — to make the rounds of the Bunker Hill Monument, Quincy Market and the Paul Revere House. I wanted to see “the town that built Jack”. I’d primed myself with the first volume of Nigel Hamilton’s biography of JFK, Reckless Youth, in which he sets out to penetrate “the many myths and protective veils” the Kennedy family had woven around their man since his assassination in 1963.

I arrived, coincidentally, after the death of JFK Junior, whose light aircraft had crashed into the Atlantic off Martha’s Vineyard. The news-stands were still full of commemorative issues of Time and Newsweek, the columnists still blethering about “the first family of pain”. But even at the best of times in Boston, there’s no need to dig out Kennedy connections: you’re constantly tripping over them.

One of the two hotels I stayed in, the glitzy Fairmont Copley Plaza, was opened in 1912 with a banquet presided over by the then mayor, John F Fitzgerald, known as “Honey Fitz”. He was JFK’s maternal grandfather. The other hotel, the Park Plaza, was the scene of tea parties thrown by JFK’s mother, Rose, when he ran for the Senate in 1952 against the Republican incumbent, Henry Cabot Lodge. One headline the day after the election read: “Kennedy drowns Cabot Lodge in 70,000 cups of tea.” Few victories can have been sweeter for the Kennedy clan: 36 years earlier, Honey Fitz had run unsuccessfully for the same seat against an earlier Cabot Lodge.

Lodge was one of the last of the Brahmins, descendants of the professional, mercantile and textile families who had founded Boston, and who looked down their noses at the Irish as imperiously as they looked down on Boston from their mansions on Bunker Hill. “No Irish need apply” was a common addendum to their job advertisements, and that was as true in politics as in skivvying.

Teddy Kennedy, who was the most prominent survivor of the family at the time of my visit (he died in 2009), seemed to have forgotten all this. Or perhaps he had forgiven. He certainly didn’t mention it on my trolley bus. Teddy’s recorded voice provided the introduction to a trip I took with Old Town Trolley Tours: “Baw’stn is the safe harbour that welcomed all eight of my great-grandparents from the potato famine and the hardship of a 19th-century Ireland… We have always considered Baw’stn our home.”

Brendan Patrick Hughes, our guide and driver, would have seconded the last bit. Like many a young man, he went west in his late teens. No sooner had he arrived in Columbus, Ohio, than he began pining for Boston, his family and the Irish. He rushed back, determined to get in touch with all three. In winter, he told us, he ran a theatre group; in summer, he led the JFK tour, warming his swotted history with the odd personal anecdote. “My Dad was milkman to the Kennedys,” he said. “Bobby’s kid beamed him one day with a rock. Bobby got so angry he kicked the kid over the hedge.”

There were 10 of us on the trolley. Two were colleagues of Brendan’s, sitting in to learn a few tricks. Among the others were a tourist from Sweden and a couple of women from Chicago with their children. None of them was terribly talkative. In the aftermath of JFK Junior’s death, we were all wary, perhaps, of being taken for Kennedy ghouls.

It was a three-hour trip, with many sights, but only two stops: one was Kennedy’s birthplace in the suburb of Brookline, the other the JFK Library and Museum at Columbia Point, the nation’s official monument to the 35th president. In between we glimpsed, among other things, the corner where Grandpa Fitzgerald had his news-stand; JFK’s favourite restaurant; and the apartment — between a dry-cleaner’s and the Capitol Barber Shop — that the president gave as his address even when he was in the White House.

We quickly got a sense, too, of how Boston differs from those other cities where the great man spent much of his time. It has none of New York’s canyons, none of Washington’s space. It flirts with glass and steel, but its soul is in mellow brick. It twists and turns and meanders. It’s compact, not to say cramped — as if its colonial planners worried that the land to their west might, after all, turn out to be less than expansive.

As we rattled along, Brendan made up for Teddy Kennedy’s lack of candour. He explained how the Irish had fought their exclusion from conventional politics by devising an electoral system of their own, giving power to “ward bosses” who did favours now in return for votes later.* He reminded us that JFK’s father, Joseph, as Roosevelt’s ambassador to Britain, had been “against World War Two and for appeasing Hitler”.

In Brookline, in the green-and-yellow clapboard house shaded by pines, the storytelling was less rounded. It had a solemnity that was doubtless occasioned by the death of JFK Jr, and a sentimentality that I was sure endured year-round. The house’s custodians, national-park rangers in khaki shirts and green chinos, painted us a picture of a family out of Rockwell: a doting father, a darning mother. Jack liked reading the story of King Arthur, we were glibly told, “so you can see the connection with the later Camelot”. In this mothballed, mummified shrine, I could see nothing of it at all.

The museum was more in keeping with the youthful vigour of the president who launched the space race. Designed by I M Pei, the architect of the Louvre pyramid, it’s a huge wedge in black glass and white stone, offering panoramic views of Boston and the harbour islands. The first thing most visitors see inside is a film in which Kennedy, in a collage of clips and interviews, tells his own story. It includes a quote from a speech he made at Yale in 1962: “For the great enemy of the truth is very often not the lie — deliberate, contrived and dishonest — but the myth — persistent, persuasive and unrealistic.”

The Kennedy myth is done no harm here. At times I felt I was not in a museum but at a campaign rally — an impression reinforced by the “JFK” buttons visitors were given on entry. I wandered from room to room reliving the 1960s: the debate with Nixon; the cold, crisp day of the presidential inaugural address; the civil-rights campaign; the Cuban missile crisis. Finally, I entered a darkened corridor in which, on a bank of video monitors, Walter Cronkite was announcing from Dallas the news of Kennedy’s assassination. It’s a story, I told myself, that scarcely needs retelling. As I stepped into the shop, I saw a little girl in star-spangled skirt tugging at her mother’s arm. When her mother bent down, the girl said: “Mom, how did he die?”

Having got my bearings on the trolley tour (or so I thought), I set off to explore Boston on my own. I got lost more than I have in any other American city. Thank goodness, then, for the Freedom Trail, which I had dismissed as a touristy gimmick. A walking tour marked by a red line in the pavement, it takes visitors past landmarks on the path of colonial Boston to freedom and independence. It also illustrated, incidentally, a transformation from white Puritan settlement to multicultural city.

Here and there it overlapped with my own Kennedy trail. In the North End, for example, minutes away from the Paul Revere House was St Stephen’s Church, which from the 1800s was the spiritual, cultural and social centre for Irish immigrants. They took it over, turning it Roman Catholic, when Protestants began leaving the area for the Back Bay and Beacon Hill. For Rose Kennedy, it was the scene of both first and last rites.

I found it had changed hands again. The plaques on its white-painted pews indicated a sharing of power — Bartholomew J Doyle a step away from Mr and Mrs Gaetano Esposito — but the signs beyond its porch suggested that the Irish had long since been supplanted: “Espresso”, “Cappuccino”, “Sambuca”, “Gelati”.

It’s on the Freedom Trail, as much as on its bijou street plan, that Boston sells itself as “America’s Walking City”. But steamy August, when I was there, isn’t the best time to test the claim, any more than it’s a time to be rubbing shoulders with the city’s numerous students. On the blissfully air-conditioned subway there were, however, constant reminders that Greater Boston was home to more than 60 colleges and universities. Every second ad was for a degree course, in anything from fashion to travel management. There were ads, too, for the JFK Library and Museum. One said: “Ironic the guy who fought communism has a stop on the Red Line.” Make that two stops if you include Harvard, where he attended university and where he is remembered in the JFK School of Government and the JFK Park.

Harvard is happy to guide visitors around its bumpy brick paths and stately quads, but it draws the line at letting them into the halls of residence. I talked myself into JFK’s former rooms, in Winthrop House, by expressing a scholarly interest.

The School of Government used the rooms to put up visiting speakers. “You won’t look at the beds, will you?” the maintenance man asked. “Someone just left and we haven’t made them.” He led me from his office down an echoing corridor where a typed notice flapped: “F14 Winthrop Guest Suite”. In the academic year 1939-40, this was home to Kennedy and his friend Torbert H Macdonald (who, like Kennedy, would skipper a torpedo boat during the Second World War and later go into politics); it didn’t seem to have changed much since. There was a sitting-room with light floorboards, cherry-coloured furniture with claw feet, a black Bakelite phone; a kitchenette and gloomy bathroom; a bedroom with two single beds. On the walls were cuttings of JFK’s articles for the Harvard magazine, pictures of JFK as a lean young student and a fuller-faced president at a varsity football game a year before his death. As the maintenance man clucked over the wattage of the light-bulbs, I sat for a few moments on the sofa. It was easy to imagine the two bright young men sitting in the same place, arguing over girls and politics, setting the world to rights.

“What does Kennedy mean to you? I asked. The maintenance man paused in his tweaking of the light. “A legend… if he was still alive, what would things be like today…?”

Emily Mullen wondered that, too. But for her JFK was more than a figure from history: he was a customer. On Sundays, he would climb the steps to the first floor of the Union Oyster House in downtown Boston, spread his newspapers on a rough-hewn table in one of the booths and ask Emily to fetch him a lobster stew. “But only when he was congressman and senator,” she said quickly, lest I get an exaggerated notion of her acquaintance with power. “He never came in when he was president.”

Some tourists call in specially to see Booth 18, which, a plaque records, was Kennedy’s favourite. Many more discover it having been sent along by their hotel concierge on the promise of a “a real Boston experience” and a taste of scrod — local market-speak for any small, flaky white-flesh fish.

Emily, a twinkly 89 with candy-floss hair, told me she remembered JFK as “very friendly — but shy”. So, did he flirt? “Well, maybe he did with the young ones,” she said, “but I was already an old lady.”

The years hadn’t dimmed her admiration for him: “He knew what this country needed… he might have been the best president that we ever had.”

And was he, I asked, having read of his reputation for forgetting his wallet, a good tipper?

“The usual, you know,” Emily said. “Sometimes he didn’t have enough money to pay, and he charged it.” And then, seeing me closing my notebook, she added: “No — he was generous.”

From the Oyster House, I followed a roundabout route up to Beacon Hill. It took me through the brutalist and shadeless City Hall Plaza — a rare lapse from Boston’s architectural good taste — and into the financial district, where the office workers, casual with history, chomped on Caesar salads next to the Irish Famine Memorial.

Beacon Hill, with its gas lamps and its uneven cobbles, its shops full of Chinese antiques and handmade cards, is still the city’s most desirable address — exclusive and, so it seemed, still excluding. “Do Not Enter”, the signs said; “Don’t Even Think Of Parking Here.”

But the ancient prohibitions are no longer in force. Kennedy has not only been admitted to the sanctum, but installed on a plinth at the front of the State House. He’s narrow of lapel and tie, broad of vision. The left side of his jacket is billowing. He’s walking at a fast clip — like a man in a hurry to change the world. Tourists come to pose beside him; boyfriends and girlfriends, husbands and wives, whole families.

A few yards down the slope is a memorial to another Bostonian and statesman. But this one is half-hidden by foliage, ignored by the tourists. The figure on the plinth is Henry Cabot Lodge — a Brahmin whose dynasty has long been eclipsed.

* * *

A week before Biden’s inauguration, the BBC began broadcasting a radio series about Irish influence in another place. In How the Irish Shaped Britain, Fergal Keane, a BBC stalwart who was born to an Irish mother in London but raised in Dublin, told the story of a relationship that stretches back many centuries, from the age of Celtic tribes to the so-called Ryanair generation of today. It’s a story that takes in proselytising monks and modern-day poets; navvies who helped build Britain and radical nationalists, intent on separation, who bombed it.

“One of the wonderful things about exploring the story,” Keane said, “is how your preconceptions can be overturned, and how you discover things which don’t fit into the nationalist narratives on either side of the Irish Sea.” In his second episode, he went to New College, Oxford, which was set up by Thomas Cromwell. This is where Cromwell, in the words of his biographer, Professor Diarmaid MacCullough, “learnt how to dissolve monasteries, something he went on to do for Henry VIII”.

Thomas Cromwell was of Irish descent: his father, Walter, had moved to Putney, south London, where Thomas was born. And it was a descendant of Thomas’s sister who would become notorious in Ireland for the terrible suffering inflicted, in the 1650s, in the name of God, on all Catholic rebels: Oliver Cromwell. As Keane put it, “I think I’m going to have to sit down, at the very thought of breaking the news to the Irish people, that Cromwell, the dreaded Cromwell… is of Irish descent.”

I know that feeling. I’ve had my preconceptions overturned — on the other side of the Atlantic.

* * *

History is never neat, but it seemed particularly untidy in the case of Irish New York. I had been strolling round the Lower East Side for an hour. I had seen the Church of the Transfiguration, built by Protestants who, as their numbers dwindled, rented and then sold it to Catholics. I had seen the headquarters of the Ancient Order of Hibernians, a self-appointed guardian of Irishness that had been founded by a Cuban. And I had been led to both places by a man whose name I had heard on the phone as Seth Campbell and who I thought might be Scots-Irish; he turned out to be Seth Kamil, whose family are Romanian Jews.

Seth, a Columbia University postgraduate student and teacher of immigration history, was one of the founders of Big Onion Walking Tours, whose purpose was to “brush off the dirt that covers New York and peel away the layers of history”. The tours began as a sideline, a way of subsidising his doctoral work, but had become so popular they left little time for study. His co-founder, Ed O’Donnell, whose antecedents are as his name suggests, was the specialist in Irish New York, but Ed was out of town during my visit (in October 1996), so Seth had offered to fill in.

This was not the disappointment it might have been. Seth, a slight man in round specs and chinos, turned out to be as knowledgeable as he was personable. More than once he reminded me that the Irish and the European Jews had a shared experience of New York: each in turn had been feared and hated, and of the immigrants who poured into the city in the late 19th and early 20th century, only Russian Jews had a lower rate of return than the Irish.

It was good, too, to hear of Irish America from someone who had no flag to wave. I thought of the cop I had met a few years earlier in Chicago. On hearing I was from Northern Ireland, she had held forth for several minutes, putting the place to rights, telling me how she was doing her bit by contributing to Noraid, the IRA’s fundraisers. Then, as I turned to go, this formidable woman, baton on one hip, gun on the other, asked me: “Would it be safe for me to visit there?”

The conversation with that cop was one of the things that had brought me to New York. I wanted to know how representative she was; how much her mixture of passion for, and ignorance of, my home turf was typical of Irish-Americans. I wanted to know, too, whether New York had a distinctively Irish community; whether, in the same way as there is a Chinatown and a Little Italy there is a Little Ireland.

I arrived, fortuitously, while the Museum of the City of New York was running an exhibition titled “Gaelic Gotham”. It was a scholarly but far from dry account of the rise of the Irish, with artefacts including both a wrench wielded by a labourer building the Brooklyn Bridge and the brown derby worn by Alfred E Smith, the working-class hero who served four terms as governor of New York and was Democratic nominee for president in 1928 (losing to Herbert Hoover).

I found cause for both shame and pride. It was the Irish, I learnt, who had been largely responsible for the city’s worst civil disturbance of the 19th century. Mobs of them rioted against Lincoln’s draft bill in 1863, fearing that if they joined the ranks their jobs would be taken by newly-freed black slaves. Eleven black people were lynched. But some Irish had been a civilising influence too. Thomas Dongan, from County Clare, had set about Americanising New York as early as 1683 by drafting a “Charter of Libertyes”.

Some critics, nonetheless, had found the exhibition not so much warts-and-all as all warts. “Nonsense,” said Elaine, whom I bumped into on the way round. “All they’ve left out, so far as I can see, is that the Irish were great Indian fighters.” The teacherly-looking Elaine, her companions told me, was an expert on Native Americans. Not only did she have lots of books on them at home but — look — she was wearing Indian jewellery and a dress of Indian pattern. Elaine told me that Custer’s theme song had been Irish. She left me with an image of his cavalry descending on the teepees, torching, looting and murdering, and all the while bellowing “Garryowen”.

The Irish asserted their identity in a less bellicose manner now, but assert it they did. Only 30 years earlier, it had seemed that they were about to slip into assimilated obscurity in the city. The opposite had happened. Green shoots were sprouting everywhere from political activism to the arts, from the Emerald Isle Immigration Centre to the Irish Repertory Theatre. Unemployment in the south of Ireland and terrorism in the north had driven a new surge of arrivals, legal and illegal. Ireland had moved from 30th among nations sending immigrants to New York to 13th.

Where did these incomers settle? The Gaelic Gotham show pointed me in two directions: to Bainbridge, on the northern edge of the Bronx, and to the East Village. Suburban Bainbridge had one of the largest Irish populations in the city; the arty Village had seen the fastest growth in Irish arrivals in recent years.

Bainbridge was near the end of the subway line, and I travelled there with timorous caution, averting my eyes from those of the tough-looking young guy sitting opposite, whose trainer tongues were licking his toes. I looked instead over the shoulder of the besuited woman next to me, and read the words “Genital mutilation: Cause for asylum?” Turning swiftly back to my three Irish weeklies, I found both an ad for Noraid and, in a leading article, words about the Sinn Fein leader, Gerry Adams, that could have sat as easily in a Tory paper in London: “Given the kind of double-talk that habitually spouts from Adams’ mouth… it is hard to believe that he could find it in him to utter an unambiguous sentence ever again.” Irish-American opinion, I was learning, comes in several shades of green.

Bainbridge’s businesses declared their allegiance with dainty shamrocks etched on their windows and the wicker cross of St Brigid on their walls. I resisted the charms of the Chariot Diner, “Irish breakfast specialist”, and, having arrived around lunchtime, headed instead for Big Paddy’s. At one end of the battered mahogany bar was a plaque recalling the role of an IRA man and prison hunger-striker in a St Patrick’s Day parade: “Bobby Sands, Honorary Grand Marshal”. Noraid, perhaps, might have usefully passed round its collection plate here, but not at this time of day. There were only three other drinkers, one a woman in a fawn twinset who might have been one of my aunts — except that the half-pint she was nursing was Bud rather than Guinness.

As the aunt was far from chatty, and Big Paddy’s wasn’t big on food, I moved on to the Greentree, a restaurant with subdued stripes and Impressionist posters on its walls. Bridget Tierney, from County Cavan, serving me my chicken cordon bleu, told me she had been in the United States for 12 years but would never consider herself an American: “I’ll always be Irish.”

Ed O’Shea, in another pub down the road, took a different line. Ed, an ex-Marine with slicked-back grey hair, told me his family came originally from Limerick. “I’m an American,” he said, “but I won’t let anyone say anything against the Irish — especially if I’ve been drinking.” The bar we met in was one of those establishments where the dollar bills and stuffed toys and discouragements to credit-seekers seem not so much to have been collected as to have assembled themselves over the years. Bainbridge was rich in such places.

The East Village had one too: McSorley’s Old Ale House, which seemed to have made few concessions to the times since 1864 (though it was forced, in 1970, to drop the last phrase of its motto, “Good ale, raw onions and no ladies”). McSorley’s had sawdust on its floor and gargoyles on its walls. Groups of Italian-American men working in data now gather at its tables, but you can still meet an authentic Irish drunk.

I did. He introduced himself as “John Francis Patrick Fucking Devine” and then insisted on hearing my own name. All of it. We marvelled at the generosity of Irish christenings and the bonuses afforded by Catholic confirmations. I left when he disappeared to the loo, promising to return and sing for me “a song I wrote myself, ‘A Mother’s Love Is A Blessing’”.

Swift’s was a different place altogether, designer-Irish, with a mural of Brobdingnagian proportions at the front, gothic chandeliers and pulpit (purportedly from one of the Dean’s churches) at the rear. JP, a ponytailed ladies’ man from Carlow, served me my pint; Sean McCracken, fresh off the plane from the Antrim Road in Belfast, microwaved my lasagne.

Sean, in common with many Irish recently arrived in the US, had chosen to make his own way rather than look to American relatives. This seemed particularly creditable in his case: his uncle in Chicago, he told me, was managing director of the soup company Campbell’s.

Leo O’Kelly, who with Sonny Condell had made up the Dublin folk band Tir nA nOg, was playing a set when I arrived. Trying in vain to classify his sound, I was rescued by a woman who said she worked for Warner Brothers, the record company. “Dire Straits meets Echo and the Bunnymen,” she said. She told me she had spent her early childhood in Northern Ireland and in a place her vowels rendered as “Scatland”. She seemed to me thoroughly American, but she insisted she was Irish.

Such declarations aside, few of the people in the pub — mostly aged between 20 and 40 — expressed much interest in Irish politics beyond the worn hope that “there’ll be peace”. They wanted a job and a few bucks in their pocket with which to see America and have some fun. Where, I wondered, were the stage bigots?

I met one at The Scratcher, another Village pub, a recently opened place of bare boards and exposed brick, its shelves packed with Tayto crisps and Bewley’s tea. A session was under way, bodhran, mandolin, tin whistle and accordion kicking up a storm to the lead of a red-haired fiddle player. It was a great bar, a great night — but for the grumpy man from County Clare.

We got chatting. I told him about the Gaelic Gotham show. “I’ve heard it’s a load of shite,” he answered. He asked where I lived, and then told me: “London’s a fucking boring place. The pubs are closed more often than they’re open.”

I left him to his prejudices and headed back to my hotel, losing myself in the gentler, small-ad world of the Irish weeklies. Here were Erin’s Nursing Services and Celtic Nannies, Flynn Brothers Rent-a-Car and O’Dwyer and Bernstein, Attorneys-at-Law. There was even “a Columbia-trained psychotherapist experienced with the Irish-American community”.

In the Emerald Personals I found that a “Sensitive, intelligent, sensual, beautiful, romantic, exotic, Indo/Russian, 43, tall, plump, Jewish female” was seeking “an Irishman of experience, 48-65”. I paired her off with “a gentle, fatherly, Irish-American bachelor, 61, who teaches history and grows potatoes”. I had high hopes of their union.

* In Coleraine, in Northern Ireland, where I went to secondary school, William Thackeray, writing The Irish Sketchbook in 1842, reckoned that “the voters were so truly liberal that they would elect any person… who would simply bring enough money to purchase their votes.”

Leave a Reply