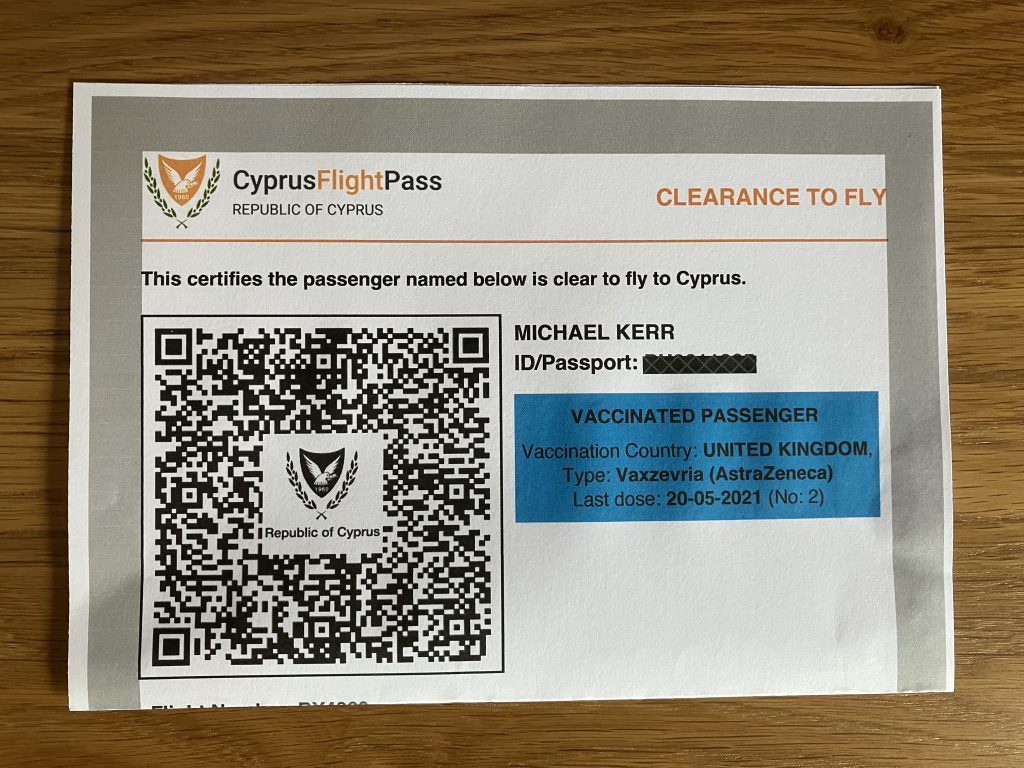

Having satisfied the authorities that I was vaccinated, and solemnly declared that I was “fully aware of the risks, dangers and hazards connected to my flight and stay in the Republic of Cyprus due to the Covid-19 pandemic”, I was clear to fly.

What would turn out to be my only trip abroad in 2021 wasn’t one I’d planned myself. Nor was it one I’d been commissioned to write about. I wasn’t taking notes, though I was making them — on a draft of a speech from the father of the bride. Our younger daughter, Julie, and her fiancé, Cieran, were marrying where they had met in August 2016, two typical singletons in the clubbing destination of Ayia Napa.

Except that they hadn’t been. They’d gone on holiday with their kids. And the grannies.

“Ayia Napa? Why on earth is she going to Ayia Napa?” I’d asked when Teri told me about Julie’s plan, and said she was thinking of going with her. Teri thumbed through some pages on her phone to show me that the resort, which I’d always associated with house, hip-hop and foam parties, catered for families, too, with shallow children’s pools, gently shelving beaches and a WaterWorld theme park. And so it was that Julie, a single mother with one child, and Cieran, a divorced father of two, were brought together not by Match.com, or OkCupid or Tinder, but through the agency of three boys still at primary school. Julie’s boy and Cieran’s boys became friends while splashing in the pool, Teri and Kim, Cieran’s mother, started chatting… and then so did Julie and Cieran.

They had decided to make their vows in July in the place where they had first bumped into each other, and have a small celebration in the sun. Thanks to events in the wider world, constantly changing advice and restrictions on travel, and understandable caution among those they had invited, it became smaller still than they had planned. In the process of organising it, Julie became better informed than most travel writers about pre- and post-flight tests, flight passes, entry requirements and quarantine.

Much better informed than her father, who, on this trip, wasn’t a scribbling traveller, looking for an angle, a way in to the place, but just another tourist. I hadn’t done any background reading — except accidentally. A few months earlier, I’d reviewed Cal Flyn’s Islands of Abandonment, a life-affirming book about dead zones; about what happens where humans move out and nature moves back.

When I started reading it, the National Trust was reporting on a year in which wildlife had been taking advantage of the Coronavirus closedown. Peregrine falcons had been nesting in the ruins of Corfe Castle in Dorset, grey partridges wandering in a car park near Cambridge, and a cuckoo had been heard at Osterley, in west London — for the first time in 20 years.

The following day, I caught up with a “Sunrise Sound Walk” the writer Horatio Clare had made for Radio 3, along the tidal flats on the Northumberland coast to Lindisfarne. He was struck by “the great green empty car parks all growing back with grass. It’s as though the whole world out here has been returned to the birds and the weather.”

Islands of Abandonment is about that process of return, and reclamation, happening on a larger scale and over years or decades. Cal Flyn travels to a dozen places — some of them literal islands — that are among the most desolate on earth. Humans have fled from them, because of war, nuclear meltdown or natural disaster, or because the fish or the oil or the money has run out. Nature has taken back what once was hers and, however bad the damage, embarked on repairs.

One of the places Flyn visits is the buffer zone that, since 1974, has kept apart the Republic of Cyprus and the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus — a state proclaimed after a Turkish invasion and recognised only by Turkey. The Green Line has proven to be truly green. In a joint study since 2008, she reports, scientists from both sides of the fence have recorded 358 species of plants, 100 species of birds (including falcons nesting on a disused control tower), 20 reptiles and amphibians and 18 mammals.

Before I arrived in Cyprus, I’d had notions of taking a day trip to the buffer zone (partly to make comparisons with another divided island: the one I’d grown up in), but it never happened, so Cal Flyn’s book serves less as a souvenir of where I’ve been than as a reminder of what I might have seen. Cyprus was in the middle of a heatwave — there were evenings when the temperature was still above 30C at 8pm — and the sun sapped any thought of venturing far from the hotel. Anyway, I wasn’t there to explore but for the wedding — a lovely one, as it turned out — and to socialise around pool, table and bar with the rest of the extended family.

This wasn’t a holiday from wearing masks; we were expected to have them on in indoor spaces shared with strangers. Not just masks: gloves, too. In the hotel dining room, we pulled on thin, disposable ones before queuing for the buffet and touching plates, tongs or container tops.

On the plane, on the four-and-a-half hour flight out and back, we had to have our masks on except when eating or drinking. I’d expected that. But a more striking illustration of the times we were in came at Gatwick airport on the way out, when Teri and I sat down for a bite at 4.30am in the Sonoma restaurant. A waiter, who looked as if he ate plenty of the restaurant’s big breakfasts himself, gave us menus and then, as soon as we had chosen, tore them up.

Those weren’t the only reasons why flying felt like a novelty. The trip to Cyprus (which I’d briefly toyed with making by train and ferry, but that would have been not only anti-social but impractical) was the first on which I’d boarded a plane since April 2019, when we went over to Northern Ireland to catch up with family. Four months later, after mulling over the cumulative depth of my own carbon footprint, and considering how I might, indirectly, be encouraging readers to deepen theirs, I decided I should stop flying as a travel writer. Early in August, Ben Ross, deputy head of travel at the Telegraph, emailed asking if I’d like to cover the maiden voyage of a much-hyped new luxury ship, sailing from New York. I thanked him for the suggestion, and said only that I couldn’t get away in September. Less than a month later, he emailed again, asking if I’d be interested in driving through the Capital Region of the US to write about fall colours. I said it wasn’t one for me as I don’t drive. “What’s more,” I added, “I’m trying to avoid flying, for reasons I’ve set out in the piece below.”

* * *

I’m trying to give up taking the plane to work. That’s why I turned down an invitation to fly to New York to write about the maiden voyage of a cruise ship. A cruise ship with a helicopter on board.

I have friends who will tell me I’m mad for not going. And I have friends who will tell me I’m mad for having taken this long to realise I shouldn’t be going. I know now which ones I should be listening to.

I’m old enough to have worked in newspapers during the transition from pages set in lead to pages scrolled on screen; I learnt basic code to build my first website. I’ve long prided myself on being an early adopter of (useful) new technology. But I have to confess to being a shamefully late adaptor to climate change.

I didn’t fasten a seatbelt on a plane until I was 18, flying from Belfast to London for a college interview. Since the 1990s, though, I’ve been clocking up the air miles. I’ve walked in the Simien Mountains of Ethiopia and the foothills of the Himalayas, run in Mombasa and Addis Ababa, cycled in the Hamptons and the Catskills, taken trains across Russia, Australia and Cuba and small boats along rivers in New York and Nicaragua — but in each case the journey began and ended with a flight (if not several flights). Often at Heathrow airport in London — the largest single source of carbon emissions in the United Kingdom.

An economy-class return flight from London to New York emits an estimated 0.67 tonnes of C02 per passenger, according to the calculator from the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO), an agency of the United Nations. That’s equivalent to 11 per cent of the average annual emissions for someone in the United Kingdom, or about the same as those caused by someone living in Ghana over a year. It’s time to mend my profligate ways.

In 2009, in the first of two anthologies on rail journeys I edited, I did briefly mention that the resurgence in train travel owed something to “global warming and the realisation of the growing contribution being made to it by aircraft emissions”. But my advocacy of trains over planes had less to do with the train’s being a minor generator of carbon and more to do with its being a major generator of stories. Great railway journeys (whether great in mileage, terrain and characters, or great in delays, frustrations and stoppages) lend themselves to great travel writing. A journey in a passenger jet, by comparison, cramps both legs and imagination; it’s a necessary inconvenience between A and B, something to be blotted out with film, book or headphones.

Similarly, I’ve managed to blot out consideration of the cumulative depth of my own carbon footprint. In 2019 I finally woke up. I was roused by a combination of factors: the Extinction Rebellion protests in Britain; the campaigning of the Swedish teenager Greta Thunberg; the BBC programme Climate Change: The Facts, presented by David Attenborough; and an interview I conducted in April with the writer Robert Macfarlane about his book Underland, which is concerned with the “deep-time legacies” we humans are leaving on our planet. Macfarlane told me he would be travelling shortly to the United States. He had also been invited several times to visit Australia and New Zealand to talk about his work; he couldn’t countenance it because of the carbon footprint.

I recycle all I can, avoid single-use plastics and I’m eating less meat, but I’ve generated a hell of a lot of carbon myself. And it’s not as if people haven’t been pointing out to me why I need to stop. One was the writer and television presenter Nicholas Crane, whom I worked with while I was on the staff of The Daily Telegraph. He decided in the mid-1990s, after careful consideration of the science, that he ought to do all he could to avoid using aircraft. In a piece for Telegraph Travel in 2006 he wrote:

“I took flights to South America, to Africa, to the Caribbean. I once flew to Australia for just a week. The articles I wrote tended to fizz with enthusiasm for the places I had been investigating. I don’t know how many readers booked flights after reading these articles. As I type these words, it’s impossible not to be wracked with guilt.”

I know the feeling.

Crane’s piece was commissioned in response to a declaration by the then Bishop of London, Richard Chartres, that we had a moral obligation to be environment-friendly and that jetting off on holiday was “a symptom of sin”. It’s a piece I would have read closely before it appeared in the paper. But there’s reading and there’s heeding.

I’ve been looking at that piece again online. I’m struck by this passage in particular: “Among the people I know well, the ‘non-adaptors’ to climate change are well-informed adults. I am absolutely mystified by this. It is no longer possible to claim that there is no connection between human activity and climate change.”

In 2006, Crane concluded: “There isn’t any option but to give up all non-essential flying.” At the end of June 2019, that declaration received support from an unexpected quarter. In an open letter, the Dutch airline KLM invited all air travellers to take “responsible decisions about flying”. On its website, it advised them to pack light, and to think about compensating for their C02 emissions. But it didn’t stop there.

It admitted that “aviation is far from sustainable today, even if we have been — and are — working hard to improve every aspect of our business”. It suggested that its potential customers consider avoiding flying — by making use of video-conferences or taking the train.**

Maybe this is a canny marketing strategy, but if it is, it’s a strategy devised in response to inescapable scientific truth. In a report in October 2018 the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which brings together leading scientists, gave warning that we have only a dozen years to keep global warming to a maximum of 1.5C, beyond which even half a degree will significantly worsen the risks of drought, floods, extreme heat and poverty for hundreds of millions of people. “It’s a line in the sand, and what it says to our species is that this is the moment and we must act now,” said Debra Roberts, a co-chair of the working group on impacts. KLM seems to have got the message. When an airline admits that flying is “far from sustainable”, and advises you to consider other options, you’ve got to take notice.

So I am. I can’t give up all flying; I have far-flung family I might need to reach in a hurry. But I do want to avoid taking the plane to work.

That will entail missing out on places I’m still keen to write about, such as the Sea of Cortez, off Mexico, which is regularly described as “one of the most biologically diverse bodies of water on Earth”. I’ve longed to go there since I read John Steinbeck’s The Log from the Sea of Cortez, an account of a 4,000-mile geography field trip he made with his biologist friend Ed Ricketts (the model for Doc in Cannery Row), on which they enjoyed “a real tempest in our small teapot minds”.

There’ll be tempests enough nearer home, as I’ve discovered recently on first encounters with the Cairngorms and the Hebrides. After Northern Ireland, where I was born and grew up, Spain is the country closest to my heart and the one in Europe where I’ve spent most time as a writer. I can get there by train.

You could argue that, if I turn down a commission that entails flying, another writer will take it; that I won’t be making a blind bit of difference. But at least I will be being honest with myself.

I could carry on flying, and try to offset emissions. But even in the best offsetting schemes, the carbon emitted today won’t be compensated for for years, by which time a lot more damage will have been done. According to the International Air Transport Association (IATA), aviation currently contributes about two per cent of the world’s global carbon emissions***, and the association predicts that air passenger numbers will have doubled to 8.2 billion by 2037.

As I write, emails are popping up with encouragements to “Follow Chile’s new Route of Parks”, “See the fall colours of Michigan”, “Make the most of your time on Earth” by visiting Antarctica. They’re not for me. I won’t stop travelling. But I’m now, professionally, aiming to be a wingless wanderer.

* Islands of Abandonment by Cal Flyn (HarperCollins)

** On its website now (2025), under “Sustainability”, KLM spells out the efforts it’s making to be more environment-friendly but still says that “Air travel is currently not sustainable.”

*** The International Air Transport Association says on its own site now that “Aviation accounts for 3% of global carbon emissions.”

Leave a Reply