We’re coming up to the end of 2021, and everyone’s talking about a photograph taken in the middle of last year. It’s not what it looks like: that seemed to sum up the reaction of Downing Street when the photo was published by The Guardian on December 19. A week earlier, the prime minister’s office had denied reports that there had been a party in the garden behind Numbers 10 and 11 on May 15, 2020 — a time when people across England were still banned from meeting more than one adult from another household socially. Now here was a picture showing Boris Johnson, his wife and two other men at a table with wine and cheese, and, in the background, three more groups of people, making 19 in all, gathered on terrace and lawn. There were bottles on tables, glasses in hand. The response of Downing Street: “As we said last week, work meetings often take place in the Downing Street garden in the summer months.”

Ah, yes, that’s just what the camera is telling us. It never lies, or so we were told in pre-digital times — but it can be used to suggest that we’re looking at something other than what was there. I like photographing landscape features and naturally occurring materials that might be something else.* Bulbous growths and indentations on the trunk of a sycamore suggest the nose, eyes and mouth of a human face. A rock I saw while walking in the Cairngorms has the body and sharp snout of a shark, and a dab of green lichen where the shark’s eye would be. Shapes scored on the sand in Worthing, by shingle moved in the tide, suggest trees — beach trees.

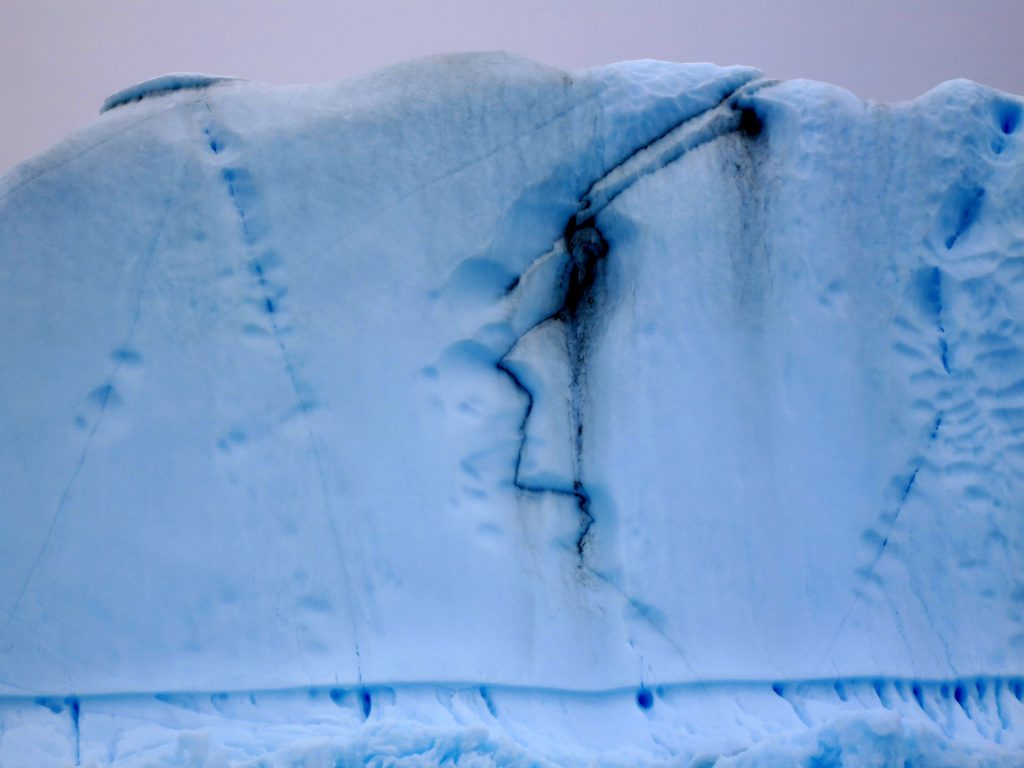

Nowhere has proved more fruitful in such offerings than the Arctic. On my first foray to the far north, in 2014, I joined an ice-breaker sailing up the east coast of Greenland. On one of our outings ashore, I came across a lump of ice like a bird’s head, with a thin beak and an eye a little too big and too close to that beak, as if the head were still in the process of being sculpted. Then, seen from a ridge-line, there was a berg that might have been a Sphinx, gazing down on a tiny Zodiac inflatable. Dark lines etched into another blue berg suggested the profile of a Native American in a war bonnet. Finally, there was an eruption of ice above a rock that was less reminiscent of a being than of that symbol of the aftermath of a nuclear bomb: a mushroom cloud.

In the Canadian Arctic a couple of years later, I followed in the wake of the ill-fated explorer John Franklin, one of whose two ships, both lost in 1845, was found again in 2014. While out in a Zodiac, I came upon a mass of ice suggestive of the shape of a polar bear, or maybe an outsized seal, its lower body a radiant blue. In the background of the pictures I took is another Zodiac, heading away. It’s as if the bear has seen off the occupants of the boat, or else decided, once they have moved on, that it’s safe to come out. On that same Zodiac outing, off the south-east corner of Somerset Island, I shot what might be the head of an ice bear in profile looking across a stretch of water. A big drip falls from its chin, as though the bear is feeling the heat: Arcturus suffering the effects of the Anthropocene.

I have a couple of shelves of photography books: some are portfolios from artists as diverse as Jane Bown and Steve McCurry; some are how-to guides for those striving to follow them, teach-ins on kit, composition and exposure. One I return to regularly doesn’t really fall into the latter category. Photography and the Art of Seeing, by the Canadian Freeman Patterson, touches on traditional principles of composition and design, but it encourages you to transcend them, to put expression before technique. Seeing, Patterson says, “in the finest and broadest sense… means encountering your subject matter with your whole being. It means looking beyond the labels of things…” The Arctic, I’ve found, is a place where that’s easy.

* * *

Delivered over the tannoy at 7.45pm, it was an irresistible invitation: “There’s a lovely pod of walruses over on the beach, belching and farting and waiting for us to come, so I urge everyone to get over there. The last Zodiac back will be at 11 o’clock.”

A quarter of an hour later, layered and lifejacketed, some 60 of us, expedition staff as well as passengers of the good ship Polar Pioneer, were swinging our legs over the gunwales of the Zodiacs at the remains of the 17th-century Dutch whaling station of Smeerenburg (“blubber town”), on the north-west coast of the island of Spitsbergen. The walruses were still several hundred yards away from us on the other side of a spit of sand, but the sun was so strong, the air so clear, that we could see the ivory gleam of their tusks. Following a briefing from our expedition leader, Gary Miller (“By law, we can get no closer than 30 metres”), we advanced slowly towards them.

About 35 of them were hauled up on the sand, lying any old way over the top of one another. Through binoculars, we watched as snores and yawns from the mouth of one lifted the tail of another. In an inlet to the right of them, a few old warriors, one armed with only the stumps of its tusks, swam obligingly backwards and forwards between sandy beach and snow-dusted peaks, till even the keenest of photographers was sated. Another reward for answering the call of the cold.

We had boarded at the northern Icelandic port of Isafjordur, to sail up the east coast of Greenland and on to Spitsbergen. Our ship was a former Russian research vessel, crewed by Russians but chartered by the company Aurora Expeditions. Aurora is based in Australia, and so were most of the passengers, many of them retired. A younger contingent included an Army helicopter pilot and three Americans, one an internet entrepreneur and the other two working on satellite systems for Lockheed. We had been drawn by the promise of “fantastic icebergs and a fairytale landscape of granite spires rising 1,000 metres above the fjords” – and by the possibility of seeing polar bears.

We got our first and only (confirmed) sighting of a bear on our first full day aboard the ship. A group of us were on the bridge (open to passengers throughout the voyage) when Gary spotted it through binoculars: “Two o’clock to the ship. Walking along a ridge. There’s a little hut on top and it’s to the left of that.”

Some others got a glimpse, and then Gary’s voice over the Tannoy was encouraging everyone to put on their thermals, wellies and lifejackets and board the Zodiacs for a closer look from just offshore. That’s the trouble with polar bears: when you know there’s one about, you also know it’s not safe to make a landing. We cruised up and down for a while, but the bear, intent on a nap, and too far away to be more than a speck at the end of the longest lens, made no further movement but a brief turn of its head towards us.

We would see plenty of other wildlife on the trip. On the water, from Zodiacs, we would have one good view at close quarters of bearded seals, hauled out on a low-lying iceberg, and occasional glimpses, in the distance, of ringed seals and harp seals. Ashore, we would enjoy regular sightings of the musk ox and the Arctic hare. The former, hard initially to separate from the terrain, was all rippling shoulders and cream legs, like a bison in gaiters. The latter was a startling white against the earthy tones of the tundra. Had it been wearing a waistcoat and consulting a fobwatch, like the White Rabbit in Tenniel’s illustrations for Alice in Wonderland, it couldn’t have looked more conspicuous.

If we had been told on the first day, however, that that would be our one and only polar bear, some, I think, might have wondered whether the trip would be value for money. By the end of our two weeks, I don’t think there was a passenger among the 50 on the ship who felt short-changed. Quite the opposite.

The Arctic is a place that makes children of us again. It’s a place where you reassess what you thought you knew. I used to think I was pretty good at estimating distances. On one outing, I discovered I’m useless. Graeme “Snowy” Snow was driving our Zodiac towards the face of a glacier. It seemed to me somewhere between 500 and 1,000 yards off. How far away is it, I asked. “Oh, I’d say about four miles,” he answered.

It was the same with icebergs, which in our minds, playfully childlike again, we turned into the Guggenheim Bilbao, or a steam engine or a medieval castle. Seeing one on its own, we’d guesstimate its size. Then a 10-person Zodiac or a single-man kayak would glide in front, and we’d realise we’d underestimated its mass by – I don’t know – maybe a factor of five or 10.

The Arctic is a place where you learn a new vocabulary. Ice is no longer just ice; it can, among other things, be brash (floating fragments), frazil (fine plates, suspended in water), grease (a stage beyond frazil, forming a soupy layer), nilas (a thin crust that bends in waves and swells) and pancake (circular pieces with raised rims, formed from the freezing-together of grease or the breaking-up of nilas).

The Arctic is a place where you realise how deceitful was the colouring of the “frozen waste” in your school atlas, and how the cliffs of a Greenland fjord (Narwhal Sund), reddened by a powerful evening sun, could double in a location shoot for Egypt’s Valley of the Kings. Ashore, too, you discover that what looked brown from the ship is bright with the red flowers of rose root, the violet of Arctic harebell and the yellow and orange of lichens.

The Arctic is a place, too, where you throw yourself out of bed at 1.45 in the morning because you’ve heard other people go by your cabin door and on to the bridge or deck, and you’re frightened that if you stay in bed you might miss something. That’s what many of us, most of us, did as our ship sailed through the summer’s last frontier of pack ice between Greenland and Spitsbergen. First I went out on deck four (where my cabin was), where several earlier risers had fingered their names in the frost towards the bow: Jan, Rita, Erica, Cathy. Then I climbed to the bridge to find most of our expedition team already there, binoculars trained on the ice.

What drew us was possibility. “You might,” said Carol Knott, the ship’s historian, “see bear prints on a floe or drag lines where a seal has hauled itself up. Very, very occasionally you might see a red stain where a seal has been dispatched by a bear.” What kept us there, hour after hour, when PPB (possible polar bear) after PPB had turned to nought, was the pink of the dawn light, the occasional flash of a minke whale fin, the skim of a fulmar over a floe, and the quietly mesmerising movement of the pack ice, the fragments bumping inwards and then outwards as if a cack-handed giant were trying to assemble a badly sawn jigsaw puzzle.

The polar bear, throughout our trip, was always just offstage. Everywhere we landed we would wait at the shore while our guides, equipped with guns and flares, satisfied themselves that there wasn’t a bear just beyond the first ridge or round the first bend. Then we’d set off through the springy tundra, one group staying close to the shore, one following a medium walk and one a long walk of anything up to three hours, usually loping in pursuit of Howard Whelan (who led photographic expeditions to Antarctica that contributed to Happy Feet, an Oscar-winning animated film of 2006 about singing and dancing penguins).

After one of Howard’s yomps, his GPS told us we had climbed to 403 metres, or 1,330ft, above sea level. Antony Watson, one of the photography tutors, joked: “That gun’s not for polar bears. It’s to put down people with blisters so we don’t have to carry them back.”

The bergs were as pregnant with possibility as the bears. As Carol put it, on one of our Zodiac outings in the fjord of Scoresbysund, “What I love about them is their sense of tranquillity. At the same time we know that inside them they’ve got this great latent power, and all this can suddenly explode. So there’s a sense of edginess all the time.” We heard lots of booms, witnessed several cracks and rolls and felt the last ripples of waves that might have done damage had we been closer when they were unleashed.

At Blomsterbugten (Flower Bay), in Franz Joseph Fjord in eastern Greenland, we came back from a walk to find we’d missed a drama. A big berg in the bay, which the kayakers had passed close to earlier in the day, had split in two, sending a wave crashing to shore that swamped the moored Zodiacs and one photographer’s backpack. Ann Ward, the ship’s doctor, and several others had been looking at the berg as it rocked backwards and forwards, but hadn’t expected it to shed ice. She showed me a video she had been shooting on her compact camera, the last of it upside down as she started running in response to Gary’s shout of “Shit! Get the gear!”

It wasn’t often we saw our guides flustered. They were, indeed, intimidatingly multi-competent, one minute briefing us in the lecture room on palaeolithic Inuit settlements or Arctic seabirds, the next easing a Zodiac through the bergs while simultaneously pointing out seals and seabirds. When their guiding was done, they’d help their catering colleagues to dry dishes in the galley or serve drinks behind the bar.

Their team spirit was embraced by the passengers, too, who quickly became a group — a group, that is, with two sub-groups. Everyone else marvelled at the endurance of the kayakers (nearly nine miles on their first day and a total close to 100 for the trip); and was mystified by the “serious” photographers (why did they need those suitcase-sized kitbags, and how could they spend so long in front of a single iceberg?).

No one, to my knowledge, minded being out of mobile phone range for the best part of a fortnight. We had a connection, briefly, during our day at the only inhabited place where we landed, Ittoqqortoormiit (population: 450 East Greenlanders and 150 sled dogs), where the Lutheran pastor gave us a graphic illustration of what climate change is doing. The permafrost under his church, built around 1938, was cracking and the building was doing the same, heeling like a ship in a storm.

On our last day aboard the Polar Pioneer, with the glacier of Lilliehook booming and cracking all round us through the crisp air, 16 of my fellow passengers, with five staff and crew, volunteered to take “the polar plunge”. One after another, either down a gangway or over the deck, they went in, while between their jumps Gary and Snowy, standing in a Zodiac below, nudged patches of ice away from the hull of the ship. “Well done, everyone,” Robyn Mundy, our assistant expedition leader, said over the tannoy. “Sixteen lunatics throwing themselves off a perfectly good ship.” And three of them did it in the nude. They were, in their own way, answering the call of the cold.

*Though it wasn’t until 2023, when reading Geoff Nicholson’s far-from-pedestrian book Walking on Thin Air: A Life’s Journey in 99 Steps (Westbourne Press), that I discovered there’s a word for this tendency to see likenesses in random images: pareidolia (from the Greek pará, beside or alongside, and eídos, image or shape).

Leave a Reply