Christmas in the Kerr household was jollier and noisier in 2021 than it had been the previous year. Our daughters and their spouses, having tested negative, had joined us in Worthing with their families. We were all throwing our arms around one another. Ten of us, one in a high chair, sat down together to lunch on Christmas Day; three of us were mad enough to go for a dip before it; and Teri — who’d been pining for a view of the sea — had taken a lift to the beach so she could cheer us on.

Teri had been feeling better in the run-up, and was even decreasing the frequency with which she took some of her meds. The plan was that she would leave the rest of us to cook and clear, but in timetabling and superintending she still ended up spending more time on her feet than she expected. She’d been lifted by the company, and the pain in her legs seemed to be less of a constant. On December 29, she even phoned to cancel an appointment for a steroid injection. A few hours later, she was wondering if she’d made a big mistake…

Then, on the eve of New Year’s Eve, she surprised me and, I think, herself. We’d done the five-minute walk to the beach, and added a couple of hundred yards along the prom. Teri, paler than she had been at the end of September, was loving being out.

I was about to turn for home when she said: “Hold on — I’d really like to see if I can make it as far as the pier.” That was nearly a mile off. She did make it (though she couldn’t hover too long at the new exhibits on the prom that had gone up since she’d last been this way, one of painted portraits of sea swimmers, another of landscapes of coastal wetlands). From there, she seemed to be on a roll. She managed to sit down in a café. She wandered on to browse in a few shops and a gallery and see — for the first time — the Christmas lights. She walked all the way back. Altogether, we were out of the house for a good two hours.

As hikes go, it was brief and unremarkable. To me, that is; not to Teri. After three months of going nowhere (apart from 10-minute car rides with our friend Jean to and from the pool at the gym), she felt the world was opening up. As we walked out through the sliding doors from Marks & Spencer, where she’d bought some groceries and a birthday present for our younger granddaughter and sat long enough in the upstairs café to enjoy a hot chocolate, she unhooked her mask from her ears and beamed at me. “This,” she said, “is heaven.”

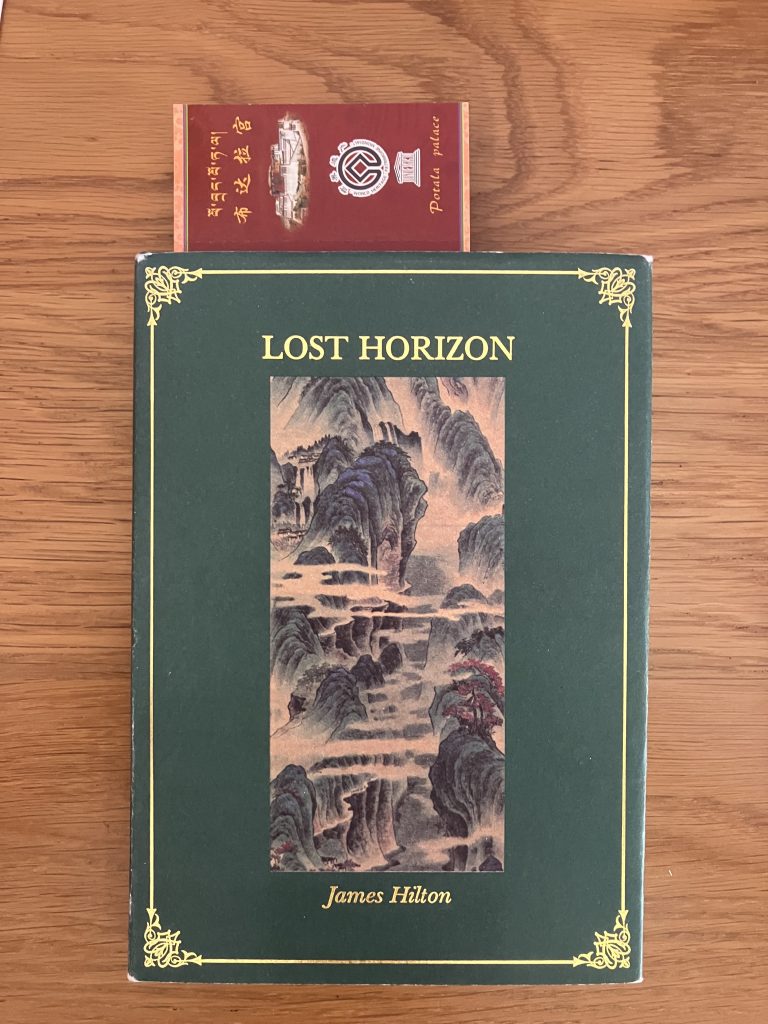

And she’s well acquainted with paradise-on-earth. In 2014 she went with me in search of Shangri-La, the Himalayan utopia at the centre of James Hilton’s 1933 novel Lost Horizon.* The bookmark in my copy of the novel is an entry ticket for the Potala Palace in Lhasa, Tibet, one of the stops on our pilgrimage.

* * *

The dog, at least, was a picture of shaggy serenity. A Tibetan mastiff, leonine mane halfway down its forelegs, it allowed itself to be stroked by tourist after tourist, to be mounted by the children scampering across the square.

Twenty yuan would change hands. The handler would persuade the dog to look up. The photographer would frame tourist and dog, the temple on the hill and “the world’s biggest prayer wheel”. Click. Click. Click…

Then the tourist was walked to a computer at the edge of the square. A photo was chosen, and not only printed but laminated. Another souvenir of Zhongdian, Shangri-La. The “real” Shangri-La.

Tibet (as opposed to the Tibetan Autonomous Region, or TAR) does not appear as a political entity on any Chinese maps. Shangri-La is on all of them – in the south-west, in the Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture of Yunnan Province.

Tibet is an indisputably real place, synonymous with spirituality; a place whose people, enduring severe altitude, a harsh climate and oppressive authorities, have chosen in the main to focus on the next life rather than the present. Shangri-La is a fiction, a tranquil refuge from worldly troubles dreamed up in 1933 by James Hilton in his novel Lost Horizon.

Hilton had never been to Asia, but he read accounts of the great missionary explorers. Then, having climbed English hills “with wild thoughts of Everest and Kangchenjunga”, he sat at a typewriter in Woodford Green, London, and transported four chance passengers in a British government plane to a place of trans-Himalayan bliss; a fertile fastness where strife is unknown, police and soldiers are redundant, and people live for centuries.

He transported many readers, too. Lost Horizon became a bestseller and a film, directed by Frank Capra. In the years since, Shangri-La has become shorthand for heaven on earth. It has been borrowed by a hotel group, which leaves soothing quotations from the novel on the pillows of its guests. It has been inscribed at the door of countless British suburban semis. It has been used to sell everything from train journeys to “the best Shangri-La yak jerky”. But it is, after all, an invention, so how did it end up being given cartographic reality in China?

It’s a long story, told well by Michael Buckley in a tongue-in-cheek guidebook, Shangri-La: A Travel Guide to the Himalayan Dream.** The short version goes something like this…

The American climber Ted Vaill (now dead) said he had been told by the actress Jane Wyatt (also now dead), who appeared in the film version of Lost Horizon, that James Hilton had told her that he was in part inspired by articles in National Geographic by a botanist and explorer, Joseph Rock, who lived in Yuhu, Yunnan, between 1922 and 1949.

In the mid-1980s, Xuan Ke, a musicologist whose father had worked for Rock, was given a copy of Lost Horizon. Hilton’s descriptions, he says, reminded him of Zhongdian, where his grandmother was from, Deqin, where he had relations, and Lijiang, where he then lived. He had the novel translated into Chinese, with an introduction featuring photographs of Rock and his home.

In the mid-1990s, local officials, on learning of his “findings”, got equally excited. The result – from which Xuan Ke has since tried to distance himself – was a PR operation as unstoppable as a Himalayan avalanche. A song, “Stepping into Shangri-La”, was released, coffee-table books were published, Zhongdian County was rechristened Shangri-La County, and a new airport that would bring millions of tourists to see it was formally named Diqing Shangri-La.

As Buckley points out, Hilton never wrote for National Geographic about Zhongdian or Deqin. He did write about them in an academic work – but that didn’t appear until 1947, long after Lost Horizon.

None of that bothers the Chinese authorities. Nor will it overly worry the newly monied, newly mobile ethnic Chinese, the Han, who in increasing numbers are heading for Shangri-La and the Lost Horizon, or, as they are sometimes rendered in translation, “Shag-rila” and the “Lost Horizontal”.

With the 60th anniversary of Hilton’s death (December 20, 1954) approaching, Teri and I set off to join them, to see how their notions of Shangri-La might compare with our own. We started in Lhasa, where earlier in 2014 the Shangri-La group opened a new hotel, one where guests prepare for the rigours of high-altitude sightseeing by reclining in an “oxygen lounge”.

The Chinese authorities will never admit that Tibet has ever been anything but part of the Chinese empire. The very journey there, however, is a reminder that it’s a place set apart. We flew in from Chengdu, in Sichuan, where one queue at security was solely for passengers to Lhasa. Dropping from a blue sky between grey-green peaks towards Lhasa Gonggar airport, our plane passed three or four military helicopters and then a squadron of fighters. Over the next three days, as we visited monasteries and palaces in the company of hundreds of Chinese tourists, it was clear from their behaviour that Lhasa, its lung-busting hills, its people and its faith were as exotic to the Han as they were to us.

Our guide, Jiang Mei, a Tibetan, did her best to educate us on architecture and Buddhist iconography, on Panchen Lamas and the wrathful deities that act as protectors. As we stepped over a threshold, she would fold her UV umbrella and lower the scarf that shielded her from the cheek-reddening sun. It was the signal that another question was coming to test how closely we had been listening.

Not closely enough. There were too many distractions: a monk collecting donations in a bowl the size of a cartwheel; the sickly-sweet smell of yak butter burning in a lantern; another monk sculpting butter, with wet hands and maths-class dividers, into a devotional object…

In Hilton’s Shangri-La, the monks are heard but rarely seen. In Lhasa, they are easier to spot, but less numerous than they were, thanks to Beijing’s fear of Buddhism. The living quarters of the 14th Dalai Lama are preserved like a mausoleum in the Potala Palace, but images of the man himself, very much alive, are banned.

Yet in the Barkhor area, the old ways endure. There may be armoured cars on the edge, bored police thumbing their mobiles, but the pilgrims still come, as they have since the 7th century. The most devout prostrate themselves en route, now rising, now falling on leather knee pads, clacking the wooden blocks they wear to protect their hands. At the entrance to the Jokhang Temple, they fall in waves, the hands of one not far from the heels of another. If there is a gap, it will be filled by a Chinese tourist with a camera.

At Gyalthang Ringha Monastery, in a pine forest not far from where we would encounter that mastiff, there were no Chinese tourists. Apart from us, there were no tourists at all. Dolkar, the cheery Tibetan guide who met us off the plane to Shangri-La, took us there en route to our accommodation. She thought we would enjoy the contrast with Lhasa.

Goats encircled us as we reached the top, then followed as we made our way clockwise around the monastery perimeter under a spider’s web of prayer flags. Their bleating, and the hammering of two men making renovations, were the only sounds.

Inside, we were met with much of what we had seen in Lhasa, but on a smaller scale – and a big surprise. Among yak-butter lanterns, in a gilt frame, was a photograph of the beaming face of the 14th Dalai Lama. It was the first of several we would see over the next few days. Dolkar told us that displays of his image had been allowed locally since March that year.

Just as tourism has turned Zhongdian into Shangri-La, so it has renamed Qiatou – now better known as Tiger Leaping Gorge Town. Here, the Jinsha (Golden Sands) River, a tributary of the upper Yangtse, is squeezed between the Jade Dragon Snow Mountain and the Haba Snow Mountain under cliffs that fall nearly 7,000ft. Legend has it that, to escape a hunter, a tiger hurled itself across at the narrowest point – still a leap of some 80 feet.

This isn’t tiger country, but that doesn’t deter the millions of tourists, who photograph the gorge, their friends and family and themselves from one or all of the platforms. It’s a circus, but a well-managed one, and if the tiger’s an invention, the power of the water isn’t. There’s an undeniable thrill in standing feet above it, watching it churn and boil, and knowing that you wouldn’t last seconds if you fell in.

Most of the coaches clogging TLG Town brought day-trippers from Lijiang. It has a population of about a million, and in 2013 drew some eight million tourists to see its “old” town, a “Venice of the east” threaded with canals. The original was flattened by an earthquake in 1996, rebuilt and then listed by Unesco as a World Heritage Site in 1997.

Our guide there, Anna, was of the Naxi, a people whose women run the home, manage the finances and do most of the work in house and fields.

And the men?

“Smoking, drinking, playing mah-jong and making babies – that’s all.” We weren’t surprised to hear that Anna was married not to a Naxi but to a Tibetan. “I bet her Shangri-La,” Teri said later, “might be a society in which men make themselves a little more useful.”

Neither Anna’s nor ours would be the old town of Lijiang – certainly not in the evening, when the gurgling of those canals is drowned by the din from clubs and bars, and a year’s worth of visitors seems to have descended at once, intent on clearing the sort of shops that sell embroidered purses on one side and catapults on the other. We fled, and went to bed with earplugs.

Black Dragon Pool Park, on the northern edge of Lijiang, which we visited a couple of mornings later, was more restful: all pavilions and bridges and trees. There are tourists, posing against the backdrop of the 5,600-metre (18,600ft) Jade Dragon Snow Mountain, but there are also plenty of elderly locals, the women sketching the slow, sinuous shapes of tai-chi, the men, in high-waisted trousers, out for their morning constitutional.

One pavilion houses the Museum of Naxi Dongba Culture. The Naxi have a system of pictographs, 1,000 years old, that is the only hieroglyphic language still in use. The Dongba, their shamen, are both caretakers of the language and mediators between the Naxi and the spirit world. In the museum we met a Dongba, seated at a desk in his red embroidered tunic, writing samples of the script with a bamboo pen on parchment.

We bought one, and I asked him, through the interpreter, what would be his idea of Shangri-La. He paused a moment, pushed his spectacles back on his nose and said: “A place at the foot of a mountain, where they have sheep and lots of other animals on grassland, and people riding horses and dancing and singing.”

And not too many tourists?

“Nowadays, there are lots of tourists everywhere, even on the highest mountains.”

So it proved when we made our pilgrimage to Jade Dragon Snow Mountain National Park, among thousands of other visitors. We drove in through fir-clad slopes, past yak grazing on the edge of a golf course, to an arena where our tour operator had suggested we see a show, “Impression Lijiang”. I feared a cheesy slice of Chinese folklore. It turned out to be a visual spectacular created by Zhang Yimou, the film director whose work opened and closed the 2008 Beijing Olympics. Massed dancers moved along ledges like human caterpillars; horsemen cantered above our heads. When the rain came down, drummers pattering in time, and the spectators in front wriggled into full-length macs, even that seemed to be choreographed.

In between weaning the Naxi off opium and teaching them farming, Joseph Rock collected seeds from Jade Dragon Snow Mountain. In the cobbled village of Yuhu, at the foot of the mountain, where Rock’s former home is a museum, we met an 82-year-old farmer who, as a boy, had been among Rock’s helpers.

Photographs are the main exhibits of the museum, including one showing Rock with a man who was his “server, interpreter, housekeeper and safety guard…They wear the same Tibetan dresses[,] which implies that they were very close friends.”

Indeed. The assumption these days is that Rock was gay – though the farmer challenged that. He told us he had “a secret” for us: Rock had had not just one but two wives, one American and one Italian. This was new to Anna. The farmer, we decided, might still have all his hair, but perhaps not all the facts.

We met another venerable resident at Baisha, six miles or so from Lijiang, a village of adobe houses renowned for handmade embroidery. Duan Shao Feng, who looked remarkably sprightly for 98, showed us round her soot-blackened kitchen, where a cat snoozed in an opening on the stove. Unlike the inhabitants of Hilton’s Shangri-La, she clearly didn’t expect to be allowed at least another century on earth. In an opening above her courtyard, she stored a recent purchase: the top, bottom and sides of her own coffin.

Workmen dug in the drizzle in many of Baisha’s cobbled streets, but its Dabaoji Palace and the neighbouring Liuli Temple were quiet and calm. It was easy to imagine Hilton’s anti-hero Conway in the former, strolling the intimate courtyards bounded by massive wooden pillars, lingering, perhaps, in the shade of a fluffy-looking red willow, its trunk split by lightning early in its 500 years.

You can still buy a DVD of Lost Horizon, though you won’t see the movie as cinema audiences did in 1937. The master reels must have deteriorated, for there are sequences where the picture freezes while the soundtrack continues. That’s Shangri-La for you, eluding everyone but James Hilton. Or has it?

In 1937, for Pall Mall magazine, Hilton wrote of his reaction on being shown the set Frank Capra had had built at Burbank, Los Angeles:

“[His] conception of the lamasery of Shangri-La…was more visual than mine had ever been; but henceforth, it is part of my own mental conception also. The lotus pool fringed by flowers and lawns, and the exquisitely stylised architecture of lamasery background, caught the exact paradox of something permanent enough to exist for ever and too ethereal to exist at all.

“I could not help a feeling of sadness that it must, presumably, be broken up when the picture was finished; I should have liked to have added a few rooms to its unsubstantial [sic] fabric and lived there myself.”

* Lost Horizon by James Hilton (Pan Macmillan)

** Shangri-La: A Travel Guide to the Himalayan Dream by Michael Buckley (Bradt)

Leave a Reply