I couldn’t get to Spain, but Spain was reaching out to me.

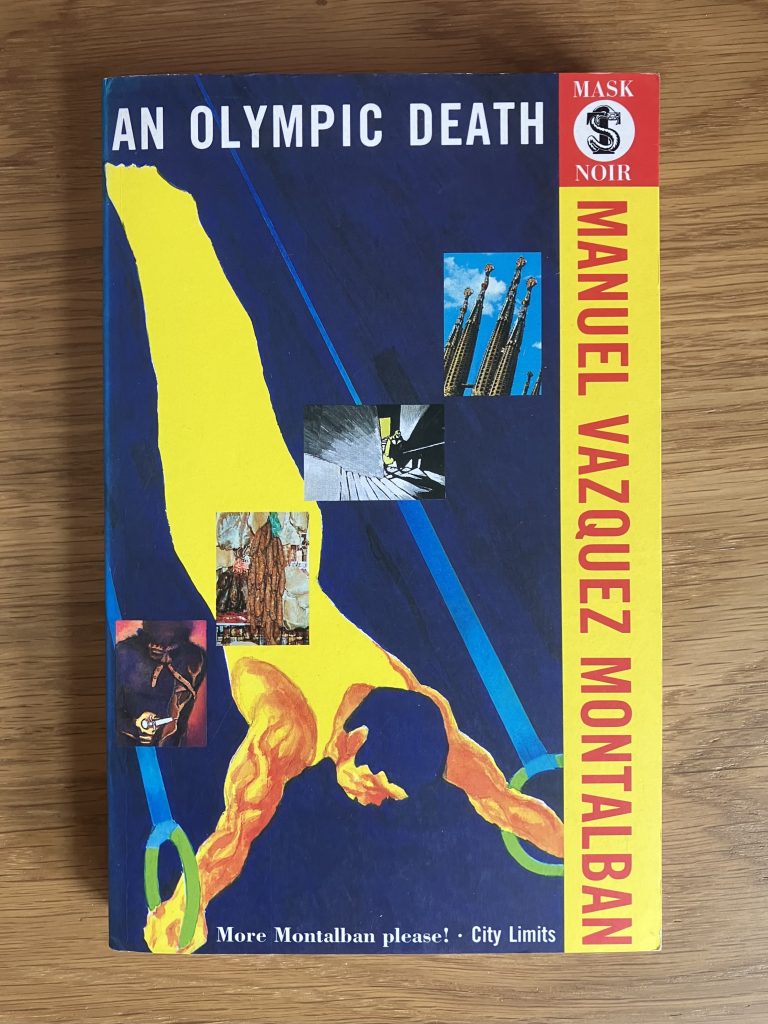

The study shelves were bowing, so I decided some of those books in front of books would have to go. I’d lifted a few stacks on to the floor, and was reaching for another, when I knocked a stack, it wobbled, and a book smacked the floor. An Olympic Death by Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, with an athlete in bright yellow flying across its cover on a trapeze against an inky-blue background. Not a great start to a clear-out: this one had to stay.

The author and columnist Montalbán (1939-2003) was a native of Barcelona, and his creation, the detective José “Pepe” Carvalho, had kept me company during my second visit to their city. In An Olympic Death (published in Spanish as El Laberinto griego — The Greek Labyrinth), he was working on two cases. In the first, he’d been hired by a man and woman from Paris to track down her husband, a Greek painter and artist’s model who had run off with a new lover. In the second, he was looking for the daughter of a wealthy man who had been seen hanging around the city centre trying to score drugs. And he was working on these cases in 1991, as his beloved city, gearing up to host the Olympic Games, was being torn apart by developers.

I took the book to my desk. I was dipping into the first chapter, where the Frenchman sees Carvalho’s rundown office on the Rambla as “an auction of leftovers from a Bogart film set”, when — ping! — in came an email with the latest from Ben Curtis and Marina Diez.

I’ve got to know them pretty well over the past eight or nine years. He’s from Oxford and she’s a Madrileña, a native of Madrid, the city where they’re raising their two children. Right now, in common with many parents all over the world, they’re home-schooling the children and not getting out much. They used to talk a lot about the museums, galleries and tapas bars (Madrid had mucha marcha — great nightlife), though they did grumble sometimes about the noise and the traffic jams.

As an occasional visitor to Madrid, I can understand Marina’s fondness for the shady paths of the Retiro Park (where her parents, in Franco’s time, were threatened with a fine for kissing in public), though I’m puzzled by Ben’s liking for the brutalist Plaza de España. Away from the city, I know that she’s drawn to the mountains and he to the beach; that he’s a big fan of Radiohead but she prefers the raspy voice and poetic lyrics of Joaquín Sabina. I know, too, that Marina’s favourite film (which also happens to be one of mine) is La Lengua de las Mariposas — The Butterfly’s Tongue, a story of a boy growing up as Spain is breaking apart in the Spanish Civil War.

And yet I’ve never met Ben and Marina. Everything I’ve come to know about them I’ve picked up from the podcasts and videos on their website, Notes in Spanish. It’s one of those wholly enriching outposts of the internet; a place where you can get a feel not just for a language but for the lives of the people who speak it all day and the country they live in. Their conversations touch on everything from Don Quijote to la violencia domestica; from the tyranny of the mobile phone to the death of the siesta. As I can’t travel and I’ve got more free time, I’m visiting the site daily at the moment. But anyway, necesito practicar.

Language learning brought Ben and Marina together. Having tried to make a living in London as a photographer, he decided to go to Madrid in 1998 to teach English. He and Marina met on una cita a ciegas con excusa – a blind date with an excuse: a session known as an intercambio in which he improved his Spanish while she improved her English.

They started making podcasts in 2005, initially to raise money for charities as part of a sponsored motorcycle ride Ben was planning with his father across India. They would sit on the bed in their flat recording straight into the built-in microphones in a digital recorder, “with our wardrobe doors open,” says Ben, “so that the clothes hanging inside would dampen the sound of the room a little bit”.

They have since developed the site in line with the so-called “freemium model”: giving away their best material, the audio, but charging for transcripts and worksheets so that the keenest learners can get more from that material. Within a couple of years they were able to give up their day jobs — Marina had been working as an IT consultant — and a few years later they had paid off their mortgage. She has since retrained as a yoga teacher and he has developed a series of online projects, including a site on mindfulness.

One strength of their recordings is that, while they did some preliminary research and talked from a list of subject headings, they didn’t write a script. The conversations are natural, unforced. In the early ones, too, where Marina is gently correcting Ben’s mistakes, and he is introducing her to such English expressions as “swot”, you have a sense that the people teaching you Spanish are on a learning curve themselves.

It’s one I’m still on. I’ve been visiting Spain as long as I’ve been a travel journalist. In an occasional series on famous streets I wrote at the start of the 1990s, one of the earliest was about the Rambla, that pedestrianised boulevard at the heart of Barcelona. Since then, I’ve gone back at every opportunity, whether it’s provided by a literary festival, allowing me to follow the trail of the poet Antonio Machado to Segovia, or a piece about language schools, for which I spent a week with a family in Valencia. My visits have taken me as far west as Santiago de Compostela (destination of pilgrims walking the Camino) and as far east as Girona; as far north as San Sebastián and as far south as Cádiz.

Teri has sometimes been with me. Several times, years ago — usually after half an hour in a tapas bar in Seville or Madrid or Salamanca — we talked about the possibility of moving to Spain for a while to work. We told ourselves we’d do it, or plan it, when our daughters had grown up. Then our first grandson arrived, and flitting to Spain seemed less important. But I’ve stuck with the Spanish.

There’s a quotation from Kurt Vonnegut, author of Slaughterhouse Five, that I used to keep as encouragement above my desk: “When I write, I feel like an armless, legless man with a crayon in his mouth.” I’ve often felt like that on returning home after a job. I’ve felt like it, too, in Spain, starting a conversation on the way in from the airport with a taxi driver or a fellow bus or train passenger. When you’ve worked for 40-plus years as a journalist, you’re in the habit of trying to get things in grammatical good order before you open your mouth. If you do that in a language that’s not your own, you dry up.

So my conversational Spanish is poor (though better than my French, which is all but forgotten). I can read much more than I can speak. I’ve often bought a book at an airport on the way home from Spain if I’ve found the first few pages easy to read. As I’ve probably read no reviews and have no preconceptions, I don’t discriminate between what’s good and bad, high-brow or low-brow. I read and enjoy what I can readily understand. In an English translation, I can appreciate the long, leisurely sentences, the elegant, looping, subordinate clauses (with further digressions in brackets), of Javier Marías; in Spanish, I prefer the short, spare prose of Juan José Millas. I buy translations in Spanish of books I’ve enjoyed in English, partly for practice, partly because it means I can read them without resorting too often, or sometimes, at all, to the dictionary — anything from Mark Haddon’s El curioso incidente del perro a medianoche (The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time) to William Trevor’s Verano y Amor (which in English was Love and Summer rather than Summer and Love).

I’ve been learning Spanish on and off since the early 1990s — shortly after I got back from a trip to France. I’d been to stay with Teri and our daughters in La Rochepot in Burgundy at a house, a converted village forge, owned by a friend and former colleague. I’d done French to A-Level, but hadn’t studied or spoken it in years, so I bought a BBC course with cassettes and swotted up before the trip. I was gratified that I could exchange a few words with the locals; that I could have a conversation of sorts with two wine-growers to whom my friend had introduced us. Back home, I bought the equivalent course in Spanish. Why Spanish? There was a musicality in it that I liked. But it was a question of utility, too: I knew by then that I wanted to see more of Spain, and to write about it, and that’s a lot easier when you can speak a few words of the language.

I wanted to see more of Spain because it felt like a second home. Why? I’m not entirely sure. It certainly had little to do with the weather: on my first trip, to Barcelona, it was warm enough to sit outside a pavement cafe on an evening in late October, which wasn’t something I was accustomed to doing on the Causeway Coast of Northern Ireland.

Maybe it had something to do with the hospitality of the Spanish, which in my experience seems undiminished from the days when Laurie Lee, carrying little more than his violin in the 1930s through a country on the edge of civil war, was fed and watered and sheltered. Their sociability, too: the great gaggles of them gathering in tapas bars. Though they don’t sit in one bar all night, the way the Irish do, and they don’t drink as much. Even now, after more than a quarter of a century of visiting Spain, I’m struck by how little beer or wine the Spanish pour in a glass — and how, when they move on to the next bar, they’ve often left quite a measure in that glass.

When I first went to Spain my suitcase was barely scuffed. As a child, I’d done no travelling. As a journalist, until I moved on to the travel section at the Telegraph in the early 1990s, I’d spent much of my career behind a desk. Barcelona was only the third or fourth city I had visited where the inhabitants’ first language wasn’t English. Though I had read that it was the capital of Catalonia, I still thought of it only as a Spanish city and of its language as Spanish. By the time of my second trip there, in 2001, I had learnt a little more Castilian, and used it elsewhere in Spain, so I was struck by how different Catalan is; how distinct it makes Barcelona from, say, Seville. When I paused for a break, I wasn’t nibbling at pan con tomate but pa amb tomaquet (crusty bread rubbed with garlic and tomato, seasoned with salt and drizzled with olive oil). The man keeping me company had keenly recommended that — but he certainly wasn’t trying to sell the city to me.

* * *

Carvalho wasn’t the sort of guide a tourist board would have chosen. He ate and drank too much, consorted with prostitutes and was completely lacking in the skills of spin-doctoring. He didn’t like the thumping and banging that were shaking his city; he yearned for the days when a hammer had always come with a sickle, and at every turn in our wanderings he told me exactly what he thought. He complained of the “pathetic dope dealers”, of “Calcutta-style traffic” and of “the pickaxe and the bulldozer, which were going to tear open the flesh of Barcelona” and bury a good part of his best and worst memories.

I admired his honesty and deferred to his knowledge, but I didn’t always agree with him. When we paused at a bar to nibble tapas or sip a Cava we often had a spat. And I always won. For if Carvalho got too much for me I could simply close the book on him.

Like his creator, Montalbán, Carvalho was sometimes as hard on his native city as only lovers can be on the object of their love. He was a fitting companion for me. On my second visit, I was a little worried that Barcelona might let me down. He would help me keep things in perspective — with assurances that the place had been ruined long before I first set eyes on it.

For many, the 1992 Olympics and the vast development projects that preceded them were the making of modern Barcelona. They turned a backward provincial city into the style capital of Europe; transformed Barcelona into Barcelon-aah. Montalbán took a different view. In An Olympic Death, he has Carvalho despairing of a city that was “already dying in his memory and… no longer existed in his desires”.

The book was in print at the time of my first visit in 1993, but I didn’t read it then. Even if I had, I’m not sure it would have soured the beginnings of my own love affair. I was spending a weekend tramping up and down the Rambla. I was there from sunrise to sundown — from the raising of the shutters on the Boquería market to the appearance from the shadows of the first ladies of the night. In between I was entertained by caged songbirds and human statues, by fortune-tellers and fire-eaters. I thought the Rambla (admittedly on the basis of limited experience) the greatest free show in Europe.

I had always intended to go back and somehow never managed it, so when the opportunity came up in 2001 I grabbed it. This time, I told friends, I wanted to see more of the city, to discover whether the rest of Barcelona was as much fun as its main street. And immediately the grumbles began. They were both general and specific. Barcelona, I was told, had grown crowded and pricey. The new Café Zurich at the top of the Rambla was not a patch on the old one. Cheap air fares had turned the place into a night-time crocodile of hens and stags. But the most damaging charge was that the city — and this was before a bombing at a bank in July 2001 that slightly injured three people — had become a dangerous place to visit. One newspaper reported that 45 British tourists had been robbed there in March. The story was headed: “Barcelona: a mugger’s paradise”.

Ah, yes, the muggers. After my first trip I wrote of the Rambla: “At one end of this street they will sell you a bird, at the other a body. In between they will take money off you for fresh fish or stale news, for soft porn or plaster saints, for a shoeshine or, if you are foolish, for nothing at all. The muggers in the side-streets strike fast and vanish faster.”

I had even witnessed the aftermath of one attack. The pianist in my hotel had begun to play (of all songs) “Strangers in the Night” when there was a scream from the front door and five or six guests tumbled in. Two had been mugged, but it turned out they had lost nothing more valuable than their room keys. As I followed them upstairs later we passed by a collection of prints, including one showing crinolined ladies taking the air in St James’s Park in London. “A gentler place for a stroll,” I scribbled in my notebook, “but a duller one.”

This time I was much more cautious. I left my camera at home. I wore a money belt inside my trousers. I followed all the advice in the guidebooks. In the event, I had no trouble at all. During the day I walked through areas rich and poor, busy and deserted, and never felt in any danger. At night I was slightly unnerved by the groups of young men hanging around in streets off the Rambla — they didn’t look to me like students of Gothic architecture — but none of them did anything worse than stare at me.

Muggers, like pigeons, congregate where the pickings are easy, which is probably why there were no groups of staring young men anywhere near the seafront. There were few groups of any kind. When I was first in Barcelona I went no farther south than the Columbus Monument at the foot of the Rambla. Beyond was the sea, but the locals were renowned for turning their back on it — except when lunching on fish — so I felt perfectly justified in doing likewise. I couldn’t this time — or not without having a look. East of the Columbus Monument, the waterfront had been transformed. Here were offices and hotels in new towers, museums in old, converted shipyards, swish apartments in the former Olympic Village, and floor after floor of shops and clubs and bars and cinemas-on-sea.

The clubs and bars, some with English names, one with an Irish theme, were heaving at night. But the development as a whole was a corpse during the day. One shop, selling, among other things, “hand-turned wind chimes”, was announcing a Liquidación por Cierre — a closing-down sale.

I walked for miles along the waterfront. At the eastern end, at the foot of the no-nonsense district of Poble Nou, there were a couple of new beaches — so new that the mahogany railings on the walkway above them were still moist with linseed oil. On the first the sunbathers were outnumbered by the litter bins. It was the same in the seafood restaurants under canvas at the Port Olímpic, where one woman raced out to press a menu on me. “I presume it’s busier at night,” I said. “A little bit,” she answered, “but not much. If it wasn’t for the weekends we wouldn’t survive.” The second beach, nearer the city centre, was livelier. Groups of children played volleyball, football and tennis. But they hadn’t found their way there on their own; they were on a school trip — being schooled to use the beach.

The development of the waterfront is on a monumental scale, which, it seemed to me, is part of the problem. I felt lost in its vast spaces; I couldn’t wait to return to the city to which it has been bolted on. With the exception of Frank Gehry’s giant fish, “Peix”, its copper scales shimmering with life in the sun, there seemed little wit in the sculpture or buildings. The Hotel Arts and the Maffre office building were just two more towers in a world that’s not short of those. Impossible to imagine a whole city turning out for the funerals of their creators, as Barcelona did in 1926 for Antoni Gaudí.

Gaudí was the master of Modernisme, a sort of Catalan equivalent of Art Nouveau, and the Sagrada Familia, a church he neither started nor finished, is Barcelona’s only real monument. It’s emblazoned on maps and tea towels and buses; an appropriate symbol of a city that was itself a work-in-progress and where, it sometimes seemed, there was scarcely a corner that wasn’t being dug up or knocked down. I went to see it again, and wasn’t disappointed. It may show evidence of others’ hands, but like everything Gaudí touched it seems not so much to have been erected as to have erupted, a creation of nature rather than man.

Another sight I intended to revisit was the Picasso Museum, but on turning up at 9.30 in the morning I found it already besieged by two parties of French tourists. I left it to them, and abandoned both plans and map. Which is one of the joys of Barcelona. There are few things you absolutely have to see, and few greater pleasures than simply going where the fancy takes you — being a wanderer, a stroller, a ramblista. When you do that you stumble upon oddities that guidebooks can’t spoil with a prosaic explanation.

Many nations, many groups of people, are grateful to Alexander Fleming for his discovery of penicillin; but why the bomberos (firefighters) of Barcelona in particular? Why should they have erected a plaque in his honour in a little backstreet square? And how did it come about that every second shop in one street in the district of Sant Pere was devoted to the sale of underwear — both men’s and women’s? And if the men and women of Barcelona liked rubbing shoulders when buying their smalls, had Marks & Spencer committed a serious error by hanging bras so far away from boxer shorts in its megastore on the Plaça de Catalunya?

Ducking into the metro to escape a shower, I decided to head for the waterside district of Barceloneta, which, I’d read, was a good place to eat lunch. On arriving I had no idea which way to go, so I followed a couple who, I told myself, looked hungry. They were, and led me straight to Golfo de Biskaia (Bay of Biscay), a cosy place with only five tables, where I had a paella and a deliciously tender steak, with beer, bread and coffee, for the equivalent of less than a fiver. Nothing pricey about that.

Crowds? Yes, there were in the predictable places, and some of those among them in the evening, beer bottles multiplying on their tables, were clearly pre-nuptial parties. Or were they? Pausing at a cafe near the cathedral, I took a seat near half a dozen Irishmen in their thirties and forties. Stags, I assumed. “No, we’re not here for the beer, we’re here for the buildings,” one of them joked. They were architects from a practice in Dublin.

When I wanted to put the crowds behind me, I had no need to go near the waterfront. One morning I walked to the wooded peak of Montjuïc, overlooking the harbour, and had no company along the way save a couple of dog-walkers and drivers practising hill starts. At the summit I saw the tour buses on which everyone else had come, the drivers enjoying a fag together while their charges looked over the Fundació Joan Miró, which was staging an exhibition of the work of Joan Brossa. A playwright and poet as well as an artist, he had fought in the Republican Army during the Civil War. His work was full of visual jokes against the clergy, the military and the authorities — and in celebration of what it means to be Catalan.

Watching teenagers in a park playing football, I was reminded of Montalbán’s assertion that FC Barcelona is not merely a football team but “the unarmed army of Catalonia”. There was a metaphor even in the mad chirruping of the birds when the shutters rose on their cages on the Rambla in the morning: here was Barcelona, freed from the dark night of Franco, and in a mood to drink all the Cava in town.

According to Montalbán, the acquisition of a taste for pa amb tomaquet is one of the proofs that an immigrant is becoming a Catalan. I devoured a pile of it with my plate of ham in the Cafè de l’Òpera, the last of the city’s great 19th-century cafés, whose Modernista interior had survived the past eight years unscathed. There was a fruit-machine I didn’t remember seeing before, but it was so awkwardly positioned that it was hard to play it without blocking the passageway, and few were bad-mannered enough to try.

The Café Zurich, on the edge of the Plaça de Catalunya, wasn’t the Zurich where eight years earlier I watched a young man bounce a tennis ball on his head and get to 32 before dropping it. The original was flattened in 1997, and this one was a sop from developers to protesters — a new café in a shiny new mall, trying to pretend that it had been there for ever. But the mall was livelier than anything on the waterfront, the Zurich was still a great spot for people-watching, and it still had more chairs on the pavement than any other cafe in the city. And no matter how far you sat from its front door, the waiters adhered to that custom, widespread in Barcelona, of not showing you a bill until you showed signs of wanting it.

And the Rambla? What of the Rambla? Pepe Carvalho had me doubting it for a while, so I left him in the hotel while I wandered along it. In the space of a quarter of a mile I met a human sphinx, watched a man (in the market) dismembering an octopus and was offered, among other things, a caricature of myself, a rosary and a tarot-card reading. Still the greatest free show in Europe? In the words of the banner that beckoned me on to it all those years ago: “Sí, sí, sí!”

Having been to Barcelona three times on my own, I was planning in 2024 to return with Teri. But protests that started in April over the damaging effects of mass tourism prompted us to postpone the trip. There were similar protests in the Canary Islands and the Balearics. In Spain, and other parts of Europe, tourism had not only recovered post lockdown, but surged past pre-pandemic levels.

Leave a Reply