Teri’s 50th birthday party had been a surprise. She thought we were going out for a pub lunch with the family; when we got to the pub, she found a room filled with her friends. Her 60th, on June 27, 2020, had to be quieter. We were able to catch up — outdoors — with some of the family. There was no kissing, no hugging, and the birthday cake was one fit for the times: no candles to be blown out but a couple of mini-fireworks on top. While she was cutting it, Teri’s Desert Island Discs played on a loop in the background, from Louis Armstrong’s “What A Wonderful World” to Kirsty MacColl’s “In These Shoes”.

I enjoyed putting together that playlist; it set me thinking about my own, and what should be included on its latest incarnation, and where music in general has taken me, and returned me, over the years.

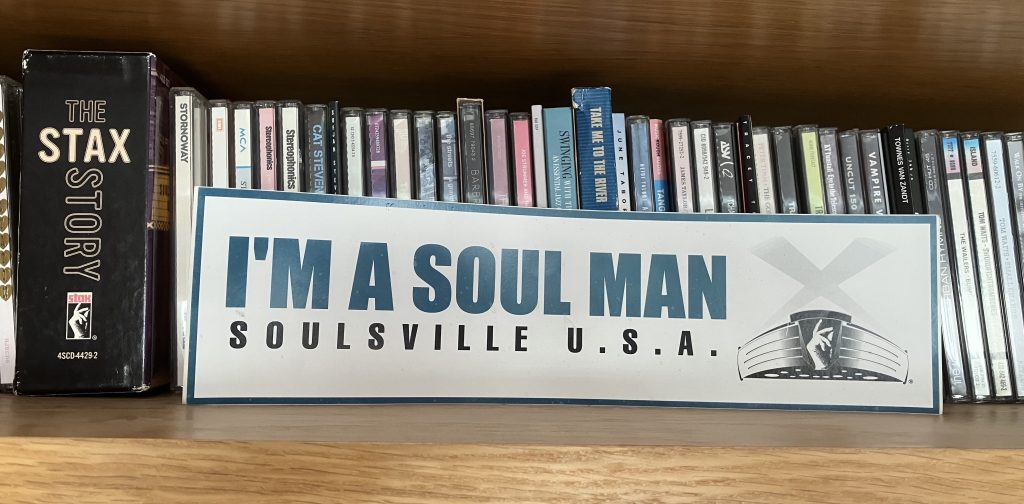

“I’m A Soul Man,” I declare, via a car sticker leaning against the CDs on one of my shelves, a sticker bearing the finger-snappin’ logo of the Stax label in Memphis — “Soulsville, USA”. And it’s true. But soul, and Springsteen, were discoveries that came later. Before them, before country rockers from Gram Parsons to The Eagles, before singer-songwriters from James Taylor to Joni Mitchell, before all the chart-topping bands I watched with my big sisters on Top of the Pops, there was my father, who didn’t read music but had learnt many a tune by ear.

The first live music I ever heard was from him, on fiddle, mandolin or accordion by the fireside at home, so something from his repertoire would have to be on the playlist. When I hear one of the instrumentals he played, I’ll recognise it immediately, though until recently I’d never registered a single title. While I was compiling Teri’s playlist, I asked my brothers and sisters in Northern Ireland and Australia, via our WhatsApp group, if they could remember any. Peter, the youngest, reckoned that “The Mason’s Apron” was a regular on the mandolin. I looked online for versions of this irresistible heel-tapper, and found one, on an album titled Kiss My Ass, by a band called The Whistlin’ Donkeys. That band is from County Tyrone, where my father was born. When I looked on their website, I discovered that their fiddle player’s surname is Kerr and, in common with my father and myself, he was christened Michael.

Then there are the songs with which I’ve sung to sleep more recent additions to the Kerr clan — first my English-born daughters, then their children — and won a moniker that’s simultaneously flattering and demanding: “The Baby Whisperer”. But how to choose between a folk song from back home, “Kitty of Coleraine”, and Paul Simon’s “St Judy’s Comet” when I’ve seen how both work their magic?

David Bowie’s pondering over “Life on Mars?” has me travelling in time rather than in outer space: in the mid-1970s the song was a regular on the jukebox in Morelli’s Lido café on Portstewart Prom, where I had a summer job making and serving ice-cream when I was a teenager. I learnt new words from holidaymakers from Belfast: they asked for “a poke” when they wanted a cone, and for “a slider” when they wanted what we called a wafer — an ice cream sandwiched between two wafers.

Dobie Gray’s “Drift Away” (written by Mentor Williams), a soul-driven hymn to the power of rock music that was recorded in the country-music HQ of Nashville, is another that takes me back to the Causeway Coast: it was a staple among “the slow ones” on those nights when I hoped to meet the girl of my dreams on the disco floor at Kelly’s in Portrush. Portrush was only three miles along the coast, but at night-time it seemed a world apart.

Portstewart had had its moment. In the 1960s (I’ve learnt online recently), the Strand Ballroom, tucked under the cliff-top site of what’s now the Dominican College, had played host not just to white-suited Irish showbands but also to Cream, John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, the Kinks and Them, whose lead singer and songwriter was one Van Morrison. But I’d been too young for all that. By the mid-1970s, after a spell as a youth club, the Strand Ballroom was empty and unused. The town did have a couple of pubs offering live music, and a sedate disco in the Strand Hotel (long since demolished and not replaced), but that was it. Portstewart was fine at weekends if you were of an age to build sandcastles or roll crown-green bowls. But if you wanted to rock, if you wanted to strut your stuff in bell-bottom trousers and platform shoes, you headed for Portrush and Kelly’s. (Kelly’s, incidentally, is just over the road from the Royal Portrush Golf Club, so that late-playing golfers in tweeds might occasionally glimpse early-arriving dancers in next to nothing.)

When I wasn’t bopping at Kelly’s, but in a mood to sing along at home, I’d lift the lid of my Alba record player and put Jackson Browne, or Linda Ronstadt, or Bruce Springsteen on the turntable. Like many others, I came to Springsteen through his third album. Just as Jonathan Raban’s Coasting is a book I love for the possibilities it opens up in travel writing, so Born To Run is an album I love for its promise. It’s a musical road movie, “lined with the light of the living”. It’s all about where you might run, what you could see and do, about where “Thunder Road” might take you.

Teri and I have seen Springsteen live twice in London: in 1988 and in 2008. I remember the second concert better, and not only because it was more recent. I blogged about it the following day; on the night itself, I found myself with tickets I couldn’t give away. I’d been lucky enough to buy two at the last minute from the friend of a colleague; she and her partner weren’t well and didn’t feel up to going. When she came to the office with them a few hours before the concert, and I went down to pay her, she gave me a couple more, because another two people in her group had pulled out. I tried to sell the tickets for her in the office, but couldn’t find a buyer. On the approach to the stadium, in north London, I tried to give them away, but the people to whom I offered them would have taken me for a tout or a crook. In the stadium we were among a crowd of 40,000, shouting, whooping, singing, whistling, and carelessly breathing all over one another. And the concert? It went like this:

What a grafter, back and forth at his end of the Emirates Stadium for the whole night, the big screen showing a vein popping on his forehead from the sheer, crowd-pleasing effort.

No, not one of those overpaid kids who play for Arsenal. I’m talking about Bruce Springsteen. Nobody works a crowd or himself as hard as Springsteen did for two-and-a-half hours last night, from the mellow mike-to-the-people chanting of “Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out” to the joyous, air-punching encore, when an audience of men and women who were largely no longer built for speed bellowed that “tramps like us, baby we were born to run”. The urge was still there, even if the capability was gone, and Springsteen drew it out.

The man who sang so understandingly in “Night” in 1975 of those moments when the “boss man’s givin’ you hell” has long since taken over the running of the firm, but he hasn’t let up. He remains committed in other respects, too, though he’s generally happy to let his songs do the talking. About halfway through the set, he played “Livin’ In The Future”, that cry of a disillusioned patriot from the latest album, Magic. He introduced it with a couple of sentences about “extraordinary rendition” (in which “terrorist suspects” are snatched off the street in one country and flown to be interrogated and, sometimes, tortured in another) and the suspension of habeas corpus — surely the first time any player’s used those words in front of an Arsenal crowd.

A recording of the Springsteen on Broadway show, which was part solo performance, part fireside chat, went out on Netflix in the middle of December 2108. I watched it a couple of times and found myself wondering: how does he do it? He undermines his credentials for writing about two themes that have featured so often in his music, the working day (he jokes that he’d never done five in a row until he took on this gig) and the driving night (he wrote “Racing in the Street” before passing his test), and seems all the more trustworthy for it. He dips into hokeyness, and out again, and somehow gets away with preceding an acoustic version of “Born to Run” with a recitation of the Lord’s Prayer. Yes, journalism is a trade that militates against hero worship, but Springsteen has come close to being a hero for me.

The Boss’s CDs* take up quite a lot of space on my shelves. So, too, does Southern soul, that musical form of the 1960s in which, as Peter Guralnick put it in Sweet Soul Music, “underlying feeling was all”. My introduction to it, a far from representative one, was probably Otis Redding’s “Dock of the Bay” (another song I associate with down-tempo time on disco nights in Portrush, though I would have heard it first, and much earlier, on the radio). Redding recorded this venture into pop only two days before his death in a plane crash, at the age of 26, in 1967. He’d begun writing it while staying on a houseboat in Sausalito, across the Golden Gate strait from San Francisco (where in 1996 I’d spend time myself “watchin’ the tide roll away”).

“Dock of the Bay” led me to Redding’s earlier, earthier, work, including “These Arms of Mine” and “Mr Pitiful”. It led me to Sam and Dave, Carla Thomas and Redding’s other stablemates on Stax Records. I loved the music of Stax, and I admired it more when I learned how it had been made. Having grown up in religiously segregated Northern Ireland, I was hugely impressed by the way this company was run in racially segregated Memphis. Here was a label, as Rob Bowman, author of Soulsville U.S.A.: The Story of Stax Records, has pointed out, that was crafting and marketing African-American culture, but on which, from the outset in the early 1960s, black and white people worked together — and this in a city where, as late as 1971, the authorities closed public swimming pools “rather than allow black and white kids to swim side by side in the scorching summer heat”.

I’ve spent a lot of money over the years on music from Memphis, Macon and Muscle Shoals; on the work of Aretha Franklin, Sam Cooke, James Brown, Al Green and Solomon Burke. I’ve got albums on my shelves, too, from British artists who went all the way to Memphis to surround themselves with that southern sound, from Dusty Springfield, whose R&B leanings provided the impetus for Dusty in Memphis (1969), to Beverley Knight, who, having visited the city in 2014 as part of her preparations for her role in the London stage musical Memphis, went back to record her tribute, Soulsville (2016). In 2003, just before the opening of the Stax Museum of American Soul Music, I got the chance to make my own pilgrimage.

* * *

The man who answered the phone at Yellow Cab was puzzled.

“Where did you say, sir?”

“To Soulsville, to the Museum of Soul, please.”

“But, sir, you’re just a couple of blocks away. You could walk there.”

No, no. Not the Rock’n’Soul Museum; I’d been there the day before. I wanted to go to the new Stax Museum of American Soul Music, which isn’t in downtown Memphis but in the south of the city.

Moments later the cab was on its way. The dispatcher at Yellow Cab still sounded as though he believed his customer had a screw loose, but, being a man of fine Southern civility, he wasn’t going to say so.

His puzzlement was understandable. South Memphis, a place of shuttered buildings, gap-toothed streets and sprouting grass, was more likely to appear on a crime report than on a tourist itinerary. In a story I read before arriving in the city, James Bishop, president of LeMoyne College, one of the few beacons in the area, recalled his own journeys to school as a pupil. In the early 1950s, leaving his black neighbourhood for high school, he’d walk a few blocks through a mainly white neighbourhood, then through black, then white, then black again. When he graduated in 1958, Memphis was a chequerboard, he said. “The city was segregated, but it was street-to-street; you had mixed incomes, with professionals, business people and working-class all living together. Today it’s mostly people on public assistance. It’s homogenised poverty.”

But I was visiting to report on new reasons for hope — Stax of them. With Memphis Horns and no end of other hoopla — a charity celebrity golf tournament, a film screening, a photography exhibition, lunches, tributes and tours — the city was about to mark the opening of the Stax Museum of American Soul Music. The museum was one half of a $20 million regeneration project; the other was the Stax Music Academy, then in its third year, which provided local children, from the age of seven, not only with training in music but with mentors. Already, I was told by Keir Thomas, a former juvenile-court probation officer on the staff, there were students showing huge potential. But finding stars, he stressed, wasn’t the objective: “We’re here to help them develop not just the ear but the personality and the heart.”

Money was coming from federal grants, private donations and fund-raising ventures, but healthy receipts from the museum would also be useful. Deanie Parker, one of the driving forces behind the venture, was confident that tourists would come pouring in — and when they did, she would be pressing the Convention and Visitors Bureau to rewrite a sales pitch that had recently been serving it well. Memphis, she insisted, was not just “Home of the Blues, Birthplace of Rock’n’Roll”. It was also “Soulsville USA”.

That was the slogan on the marquee at the front of the Stax Records building when Deanie Parker worked there as a secretary and then as a publicist; the same slogan she and her team were now applying, with municipal blessing, to two square miles of south Memphis. That area includes not only the Stax complex but also the house where Aretha Franklin was born and Royal Studios, home of Hi Records, where Al Green recorded “Tired of Being Alone”, “Let’s Stay Together” and “Call Me”, and Ann Peebles declared: “I Can’t Stand the Rain”. (It was to Royal Studios, too, that Beverley Knight would travel decades later to make her album, Soulsville.)

Stax, a name synonymous with black music, was founded by a white brother and sister: Jim Stewart (the “St”) and Estelle Axton. They were bank clerks during the day, desperate to be involved in music at night. They had little interest in blues or gospel; it was pop and rockabilly they began recording on their label, which they initially called Satellite, in a garage in 1957. By luck, they chose as new premises a couple of years later a former cinema in an area where white people were rapidly being replaced by black people. By necessity — they were short of cash — they had to make the most of a studio with a lofty ceiling, a sloping floor and “voice of God” cinema speakers and to turn what had been the candy kiosk at the front of the building into a record shop.

All these factors contributed to what became known as “the Stax sound”. Musicians and singers, experienced and aspiring, black and white, began hanging around the shop. Word got around that here was a place where you could make music as well as buy it. Much of the talent just sidled through the studio door.

In the following decade and a half, in the US alone, Stax notched up 166 hits in the top 100 of the pop charts (13 in the top 10) and 265 in the top 100 of the R&B charts (81 in the top 10). Some of them, such as Sam and Dave’s “Soul Man”, and Otis Redding’s “Dock of the Bay”, are never off the airwaves, well known as the products of a label that, unlike the bigger Motown in Detroit, made no attempt to sweeten its soul for a white audience. Others, by way of commercials and theme tunes, have insinuated themselves into the consciousness of millions who know nothing of rhythm and blues. The BBC’s theme for cricket coverage, the one that opens with a sound like a wooden spoon being tapped on the bottom of a saucepan — it’s “Soul Limbo”, by Booker T & the MGs, the Stax house band.

The Stax story, amid arguments about over-expansion, problems with cash flow and allegations of fraud, ended messily in 1975. Fourteen years later, the building was torn down. Now, even if it’s showcasing the music of the past rather than shaping the music of the future, it’s standing proud again. Memphis itself has recently been attempting a similar revival. For much of the 20th century the city’s history was bound up with the struggle for civil rights. Racial conflict drove residents and businesses from the centre, a trend that accelerated after the murder in 1968 of Martin Luther King.

By 1980 the only business of any size left on Beale Street, byway of the blues and the most famous thoroughfare in the city, was Schwab’s, a variety store founded in 1876. Schwab’s is still there, still selling everything from “cast-iron skillets to stick horses to old-fashioned candy to ukuleles”, but now it’s framed by bars and restaurants and souvenir shops. Where there was erupting Tarmac and earth and grass there are cobbles; cobbles that in pre-pandemic days would have been strolled every evening by tourists wandering from the Hard Rock to the Rum Boogie Café to BB King’s.

The Peabody Hotel, a repository of gentility that had closed between 1975 and 1981, was once again serving afternoon tea and staging its parade of ducks to and from the lobby fountain, a ritual that seemed bizarre until I saw how much parents spent on duck T-shirts and duck umbrellas in the lobby shops. I shared the lifts with white cotton traders talking tonnage, white judges in blazers talking of their swearing-in, but also a few young black men, in tracksuit bottoms and mesh vests, talking about the basketball scores.

At the National Civil Rights Museum, on the site where King was shot, an optimistic closing film told of a black man, once forced to the back seats in a bus, who was now running a bus company; of black families sitting among white at the shiny new ballpark across from the Peabody. But Memphis still bears scars, and black residents continue to suffer disproportionately from poverty.

(Following the death in 2020 of George Floyd, the black man killed in Minneapolis by a white police officer kneeling on his neck, there were 12 days in a row of protests in Memphis. At one rally — held at the spot where 46 black people were massacred in 1866 by a white mob — the Rev Regina Clark said: “We see the violence of injustice, we see the violence of racism against black people, Latinos, First Nations and people of colour. We know this violence is a threat to all humanity in this yet-to-be-perfect union.

Listening again to Beverley Knight’s Soulsville, I’m reminded, too, of how much less-than-perfect is the United Kingdom. Knight was born and raised in Wolverhampton by Jamaican parents who came to England as part of the Windrush generation, and has spoken of the racism she has experienced. On Soulsville, in “I Won’t Be Looking Back”, she sings of how she was made to feel in a place that had a “welcoming sign” at the door.)

Judging from the number of car parks, the locals do little walking in Memphis, and the visitor isn’t inclined to challenge their example. A few minutes from the Peabody, on South Main, planters full of fresh pansies stood outside boarded-up shops. Dusty signs said “This space for lease” and “66,000 square feet for sale”. The trolleys, thick with new paint, recommended as a way for tourists to get around, often had no occupant other than the driver. The shuttle bus run by Sun Studio was busier, but then it was free, and it connected most of the sights beyond Beale Street that draw visitors: Sun itself, where rock’n’roll was invented; the Rock’n’Soul Museum; Elvis Presley’s Memphis (a restaurant); Heartbreak Hotel; and, of course, the place where the King made his home in this life and started his journey to the next: Graceland. The shuttle didn’t run to Soulsville, so unless you had your own set of wheels, you had to take a cab, having ordered it by phone or stepped into it outside your hotel; Memphis wasn’t exactly jammed with taxis, so you couldn’t expect to hail one on the street.

“I know, I know,” Deanie Parker said when I put this to her. “It’s being arranged.” She’s a tiny, elegant woman, with hair the colour of steel and determination to match. She talked constantly of how this had been a team effort, how all the artists and staff at Stax had played their part. Rufus Thomas, who with his daughter, Carla, had Stax’s first hit with “’Cause I Love You”, was here offering his help “when there was still nothing but grass and glass on the ground”. But there was no doubt that her energy and PR skills had been hugely important. When I asked what motivated her, she answered: “I just wanted to hear the neighbourhood sing again.”

On this very spot, she was one of the first to hear Otis Redding sing, at the start of a career that would be cut short by that plane crash in 1967. As we watched the museum’s introductory film, including electrifying, and previously unseen, footage of Redding and Sam and Dave on tour in Europe, she was visibly moved by the reminder of what had been lost. But she had to look to the future now; there was a museum to be got ready. She left me to wander around, to make a journey from roots to riches; from a one-room delta church, built around 1906, in which everything but the fancy pulpit was hand-built by the congregation, to the turquoise-and-gold Cadillac that Stax bought Isaac Hayes in 1972 after he won his Grammies for the soundtrack to Shaft, the tough-talking story of a black private eye who gets entangled in a gang war in Harlem.

DVDs aside, the museum was low-key, low-tech, with only two exhibits that could be called interactive. On one, you could compare the original recording by a Stax artist with a cover version. On another, you could play sound engineer, adding or subtracting piano or drums or keyboard to make subtle — or not so subtle — changes. Not that you would want to do too much of that. The originals can’t be improved on. Having listened to them over so many years, however, wondering just where that line came from, or how they got that riff, I found it was great to hear the answer in the voice of Jim Stewart, or Booker T or David Porter, who with Isaac Hayes wrote so many of the hits. On the way out — towards the Satellite Record Shop, of course — there was a corridor lined with every album and single the label produced. Among them was a 45, “Until You Return”, written and recorded by one Deanie Parker.

I mentioned this down the road, in the red-brick house serving as an office where Deanie and her team were having their lunch, one hand clasping a turkey roll, the other stuffing an envelope or finishing a press release or lifting a ringing phone, or offering me a few souvenirs of my visit, including that “Soul Man” car sticker.

“The only reason I didn’t reach the heights of Mavis Staples and Chaka Khan,” Deanie joked, “was that the world wasn’t ready for my music.”

There was endless coming and going: TV crews, delivery men, well-wishers. People took a seat, chipped in, moved on. This, I sensed, was how it might have been in the heyday of the studio. Deanie introduced me to Sandra Jackson, a white woman who, as one of the Goodees, a girl band on Stax’s subsidiary, Hip, scored a minor hit with “Condition Red”, which rivalled “Leader of the Pack” for teenage angst. Sandra said she felt the buzz when she first stepped over the threshold. “I told Deanie, ‘I want to work here.’ I’d have taken the garbage out if I had to. I couldn’t wait to get up in the morning and go to Stax.”

A shame, I said, that it was all gone, that the best was over. But Deanie Parker wasn’t having that kind of talk. “Just wait,” she said. “There is no question in my mind that you’ll be back here writing about the next soul music star — discovered here on the campus of the Stax Music Academy.”

*Springsteen CDs on my shelves now include his own tribute to soul music, the 2022 covers album Only The Strong Survive.

Leave a Reply