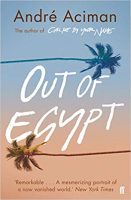

Out of Egypt

By André Aciman

Faber (£9.99)

Out of Egypt is the extended story of an extended family, one that made its home in Alexandria in the first half of the 20th century. It’s a dazzling evocation of a time and a place, and all the more so when you consider that the author was only in his mid-teens when the tale he tells was drawing to a close.

Out of Egypt is the extended story of an extended family, one that made its home in Alexandria in the first half of the 20th century. It’s a dazzling evocation of a time and a place, and all the more so when you consider that the author was only in his mid-teens when the tale he tells was drawing to a close.

The book was published in the United States, where André Aciman now lives and works, as long ago as 1994. It’s finally appearing in Britain, presumably, because of interest in his back catalogue generated by the Oscar-winning film Call Me By Your Name, a coming-of-age story based on his first novel (2007).

When I began Out of Egypt, it was the vividness of its social history that struck me. When I finished it, it was the timeliness, maybe even the necessity, of its publication. Tens of thousands of people had taken to the streets in France to protect at a recent rise in anti-Semitic attacks, and in Britain a Labour MP had quit his party over its attitude to Jews. Aciman’s family was Jewish, with Italian and Turkish roots. Until 1905, they lived in Constantinople. Then one of them, who had befriended the future king of Egypt, Faoud, staked all of his hopes on that friendship, and persuaded his parents and siblings to sell everything and move to Alexandria.

Theirs was a family of dreamers and schemers, one that had its ups and downs, but the ups included Sundays in the gardens of the king, chauffeur-driven arrivals at the exclusive Sporting Club, and summers in a house by the beach. It was a life of privilege — but also of impermanence. On the one hand there’s the great-grandmother, insisting to the Egyptian servants that her ginger biscuits be served separately from the rest of the pastries; on the other, there’s the neat stack of “very small” suitcases in the hall, in readiness for “that day when the Nazis would march into Alexandria and round up all Jewish males above 18”.

The Nazis were halted at El Alamein, but the threat didn’t end there. The family sought refuge in the matriarch’s home three more times: during the Suez War, in 1956; a decade later, before the last of them — following months of abusive late-night telephone calls — were expelled under Nasser; and in 1948, when Zionist agents beat up Vili, Aciman’s uncle, for spying for the British, and threatened to do the same to other men in the family.

Vili — who had been a soldier and a swindler as well as a spy — fled to Italy, then England, where he changed his name, converted to Christianity, and finished his years “in lordly penury” on a sprawling Surrey estate. The book opens there, with Aciman unsuccessfully pumping his opportunist uncle for memories of the old days — “of time lost and lost worlds”.

In truth, Vili’s hardly a reliable witness, and Aciman hasn’t much need of him. He learnt early to see for himself, and the elders he presents put me in mind of Larkin’s “fools in old-style hats and coats,/ Who half the time were soppy-stern/ And half at one another’s throats.” His father was having an affair; his deaf mother was seen by her mother-in-law as “a cripple”. As a child, Aciman felt happier among the servants; as a teenager, he relished the company of his young governess and his Italian tutor, whom he joined in singing arias from Tosca in the car on the way to the beach.

The Proustian relishing of the daily round (Aciman teaches a course on Proust at the City University of New York) extends downstairs. He tells how the song of the family’s washerwoman would be taken up by her counterparts in other houses: “Without budging from their places, without seeing the others, they had learned one another’s names and would call them out and swap entire life histories like ships exchanging signals in the fog.”

But surely, I found myself thinking later, these washerwomen might have got to know each other in the street… And weren’t Aciman’s powers of recall just a little too sharp? From a time when he was young enough still to sit on Father Christmas’s lap, he reports verbatim his elders’ conversations about the latest political shifts and what dangers they might pose for the Jews. But those questions came afterwards — while I was reading, I was borne along by the brio of the writing. MK

This review appeared in The Daily Telegraph on March 23, 2019