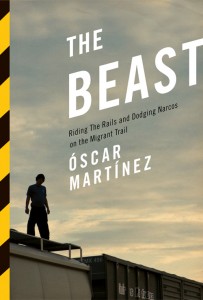

Every year, hundreds of thousands of men, women and children from Central America, intent on a better life in the US, make a hellish journey through Mexico. In ‘The Beast’, ÓSCAR MARTÍNEZ doesn’t just report on that journey; he makes it himself. Below, he reports from the roof of the goods train – ‘La Bestia’. Above is CNN footage of migrants making the same trip

The whistle blows long and loud in the darkness. The Beast is coming. One blow. Two blows. The shrill call of the rails. Time to get moving. Tonight there are a hundred or so of them. They wake, shake off their sleep, heft packs onto their shoulders, grab their water bottles, and start onto the path of death.

Some of the silhouettes stand out against the other, more furtive shadows running next to the train. Thirty or so sharp, strong, looming profiles. These are the warriors. From their hands, like extensions of their bodies, flash their makeshift weapons of defence. These are men willing to take a stand against the bandits. They know that together they’ll have a chance against the rail-pirates waiting for them in the darkness of the jungle.

The men huddle and plan next to the rails as they wait for the engine to hook up with the twenty-eight boxcars to begin the journey. The group’s decision is unanimous: if it’s necessary, they’ll fight.

The majority of the cars stand on one rail line, but there are also some lined up on adjacent tracks. There’s an extended moment of uncertainty: nobody knows which train to board. The hundred or so shadows turn their heads between the two lines, trying to read the train’s signals. The shadows move along the one line to get a better look, and then return. It’s a lot easier if they can figure it out before the cars take off, otherwise they’ll have to board on the run.

Though this will be my eighth trip, I still haven’t gotten used to it: the back and forth of hurling, frantic silhouettes, the metal clanking of The Beast enveloping everything, hardly a moment to think. It’s a sensation between the excitement of the ride and the fear of the uncertainty. All we know is that we don’t want to miss the train, that if we jump on the wrong car we’re going to have to wait and wait and wait. And when the time finally comes, we’ll only think of ourselves, we’ll concentrate on the ladder we’ve picked out, on climbing it safely, hoping that nobody gets in our way.

The train is a long series of uncertainties. Which cars are going to be leaving? Which one will take you to Medias Aguas and which to Arriaga? How soon will it leave? How will you duck any rail workers? To avoid an assault, is it better to ride the middle or the back cars? What sounds signal you to jump on? When do you get off? What happens when you need to sleep? Where is the best place to tie yourself to the roof? How do you know if an ambush is coming?

Between the two lines, the group of thirty make their decision: the left-most rails. One after another they scamper up the ladders and settle on the top of boxcars, staking their claim. This sixty-feet radius will be their base during the six-hour journey. They’ll cling to any ridge or pole to keep from falling. It’s a space they’re willing to fight for.

These men have already kicked off one dark-skinned teenage Salvadoran. Earlier in the afternoon, the young gangster, recently deported from the States, was smoking marijuana outside the hostel in Ixtepec and sitting apart from the group. The other men didn’t trust him, didn’t want to risk having a gangster ride with them. “You’re not coming,” one of them said simply, clearly an order, the whole group of thirty watching over his shoulder. And then the young gangster, looking back into that group of faces, backed down.

Eduardo and I pick our spot on the top of a car with a group of Salvadorans, Nicaraguans, Guatemalans, and Hondurans.

The few women on board settle themselves on the balconies between the cars. A few lucky migrants even secure the bottom platform, which is safe from the wind and passing branches and wires. The remaining passengers have only metal beams to hang on to. They’ll ride on top, dodging wires and branches, shivering in the constant currents of wind.

The group of thirty is composed of bricklayers, plumbers, electricians, farmers, labourers, and carpenters, all recently turned warriors. The four Guatemalan men closest to us are brothers. They’ve recently been deported from the United States, but are headed back to the country they consider their home. One of them is an ex-soldier who left a job as a bricklayer. We also meet Saúl, who is so skilled at getting on and off the train that, after tying his bag to the roof, he swiftly hops off to snag a cardboard box lying next to the rails. He’ll use the box as padding against the sharp fibreglass of the roof.

Finally the engine lurches forward, pulling the twenty-eight cars behind it. The hard clack begins at the head and shudders down each car all the way to the last: tac, tac, tac, tac… One car after another pulled by the powerful engine, people latching on to whatever they can. Many have been injured in this initial thrust when, ignorant of the rules of The Beast, they’ve rested a foot between two cars. The molars, they call them. As its cars domino and grind together, The Beast, like a hammer crushing a nut, has smashed many feet.

And yet the danger of the initial thrust is outweighed by one invaluable advantage: you can get on before the train starts moving. There are plenty of other stops—Lechería, Tenosique, Orizaba, San Luis Potosí—where rail workers and guards won’t let anyone board near the station, and you have to jump on the train farther down the line, once it’s already speeding ahead.

On one of my earlier rides, Wilber, a twenty-year-old Honduran who acts as a guide for the undocumented across Mexico, gave me a beginner’s course on how to board a moving train.

“First, you read its speed. You let the handles of the cars hit your hand to see how fast it’s going. You have to feel that. If you’re just watching, the train will trick you. If you think you’re ready, get up next to it, grip on to a handle and run with it for about sixty feet to match its rhythm. When you have its pulse down, you latch on with both hands, then, only using your arms, keeping your legs away from the wheels, lift yourself up. You step on the rung with your inside foot, not your outside foot, so that your body swings away from the train and you don’t get sucked under.”

When I tried for the first time with Wilber, we were in Las Anonas, a small pueblo between Arriaga and Ixtepec. The train was moving at about ten miles an hour. I made the basic mistake that’s maimed so many beginners: I forgot the trick about which foot first and I stepped with my outside foot. I was hanging on by my left hand and the sudden thrust pushed my foot back to the ground. The train dragged me for a few yards until, luckily, a few migrants jumped down to disentangle me.

Wilber thinks that travellers who are mutilated early on in the journey are “lucky.” The train is usually going slowly enough, he says, that, after getting maimed, they get the chance to make a new decision.

“I saw one guy,” Wilber says, speaking as calmly as if he were remembering a soccer match, “who got his leg chopped off by a wheel. The guy just couldn’t lift himself up once he was already running. And since the train was going so slowly, he had enough time to see his chopped leg, think about it, and then put his head under the next wheel. You know,” Wilber says, “if he was heading north because he couldn’t get work down south, what could he possibly find with only one leg?”

Why don’t they let them board before the train starts moving? Why, if they know that the migrants are going to get on anyway, do they make them jump on while it’s already chugging? It’s a question that none of the directors of the seven railroad companies is willing to answer. They simply don’t give interviews, and if you manage to get them on the phone, they hang up as soon as they realize you want to talk about migrants.

THE RIDE BEGINS. The Ixtepec rail lights fade into the distance. We cut through dark plains outside town, which glimmer in the eerie light of the yellow full moon.

These are the migrants riding third class, those without either a coyote or money for a bus. The men repeat this fact over and over. They will be sleeping alongside these rails for the bulk of the trip across Mexico, hoping that as they rest they won’t miss the next whistle and have to wait as long as three days for another train. They’ll travel in these conditions for over 3,000 miles. This is The Beast, the snake, the machine, the monster. These trains are full of legends and their history is soaked with blood. Some of the more superstitious migrants say that The Beast is the devil’s invention. Others say that the train’s squeaks and creaks are the cries of those who lost their life under its wheels. Steel against steel.

Once, riding on top of the train in the dark of night, I heard someone say: “The Beast is the Rio Grande’s first cousin. They both flow with the same Central American blood.”

The stretch from Ixtepec to Medias Aguas, crossing from Oaxaca into Veracruz, is 125 miles long, which lasts, at the very least, six hours. Six hours in which the train curves away from highways and into the desolate wilderness where it sometimes stops in the middle of the mountains to load cement or attach new cars. Sometimes the halt in the mountains can last up to two days. It’s a waiting and guessing game. This leg of the ride can last anywhere between two and ten hours.

The best place to chat to a migrant is on top of the hurtling train. You’re considered an equal there. You’re in their territory and have, by boarding the train, signed a pact of solidarity. You share cigarettes, water, food, and are ready to defend the train from attack if necessary. The pact ends when you get off the train. And then you have another opportunity to sign again, to get back on the train or not.

Talking is the best way to stay awake, to keep yourself from becoming another one of the legends, another victim mutilated in the darkness, bleeding to death by the side of the tracks.

Extracted from The Beast: Riding the Rails and Dodging Narcos on the Migrant Trail by Óscar Martínez (Verso). Translation © Daniela María Ugaz and John Washingon, 2013. First published as Los migrantes que no importan, © Icaria Editorial 2010.

Extracted from The Beast: Riding the Rails and Dodging Narcos on the Migrant Trail by Óscar Martínez (Verso). Translation © Daniela María Ugaz and John Washingon, 2013. First published as Los migrantes que no importan, © Icaria Editorial 2010.

Leave a Reply