‘The Foundling Boy’ by MICHEL DÉON is both a coming-of-age novel and a vivid portrait of a world that died between the wars. It tells the story of a child born in the year of the Treaty of Versailles, 1919, and left outside the door of a couple in Normandy, who raise him as their own. His childhood is spent between their simple home and La Sauveté, the estate of their employers, the Du Courseau family. In this extract, Antoine, owner of La Sauveté, motors through France in his new Bugatti, stopping, along the way, at a little resort he’s never heard of: Saint-Tropez

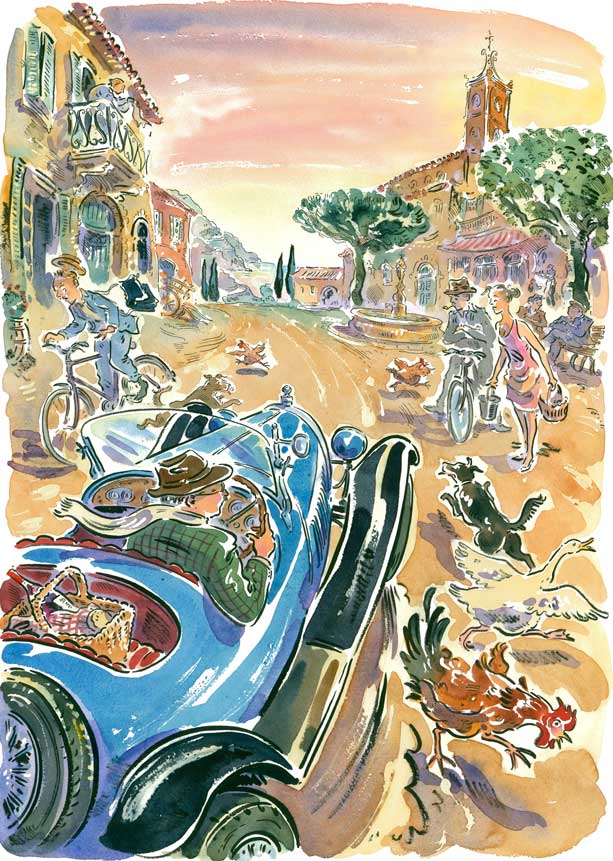

Until the war, Antoine du Courseau had taken little or no pleasure in analysing his own feelings, and in his private moments was frightened to discover in himself a kind of unease for which he could not find a name. He would have been amazed to learn that the feeling in question was one of boredom. Boredom that he banished in his own way by straddling whichever Martiniquaise was working at La Sauveté at the time or by reversing his Bugatti out of the garage to race the country roads using every one of its thirty horsepower, scattering hens, dogs, cats and dawdling flocks of sheep as he went.

It was thus that, one afternoon in the summer of 1920, at the wheel of his sports car, he reached Rouen, crossed the River Seine and, having sent a telegram back to La Sauveté telling them not to wait, continued via Bernay and Évreux deep into an agricultural Normandy that was foreign to him. France seemed terrifically exotic to him, so full was his mind’s eye still with the memory of landscapes burned by the sun, cracked by cold or glowing with poppies that he had encountered in southern Serbia and Macedonia. This was a France he did not know, unless he had forgotten it, and it worked its way back into his mind via neat villages full of flowers, hundreds of delicate churches, and a countryside drawn in firm and well finished lines and softly coloured in grey, green, and red brick. The war had not passed this way, and to see the parish priests out walking, mopping their brows with big checked handkerchiefs, the postmen on bicycles in their straw hats, the children mounted atop hay carts bringing in the second cutting, you would have thought the whole conflict merely a bad dream born of men’s unhinged imaginations.

The greedy Bugatti ate up the kilometres, trailing a plume of ochre dust behind it, its engine burbling with a joyful gravity that communicated itself to the driver. The indefinable malaise Antoine suffered from was left far behind, at La Sauveté. At petrol depots he stopped to stretch his legs and answer the questions of mechanics who walked respectfully around the car, examining it. The same model, a Type 22 driven by Louis Charavel, had recently won the Boulogne Grand Prix, and the automotive world was beginning to talk about Ettore Bugatti and his little racing cars that were beginning to eat away at the supremacy of the monsters made by Delage, Sunbeam, Peugeot and Fiat.

Antoine felt so relaxed that he stopped to have dinner at Chartres, after changing his tyres and four spark-plugs and filling up with petrol. Afterwards he drove straight out of the city and into the night. His headlamps lit no more than a few metres of the road ahead and he had to ease back on the throttle, driving inside a small, tight circle of light that threw trees up as he passed and pierced the thick shadows of sleeping villages.

Two or three times on the outskirts of a town he almost drove into an unlit farmer’s cart. He felt as if he was playing Russian roulette and stepped on the accelerator once more, drinking in the cool night in deep draughts, as dense as a mass of black water unrolling over him. At about two o’clock in the morning, apparitions began rearing up at the roadside. He was driving in a trance that was close to drunkenness: columns of soldiers in sky-blue uniforms were marching northwards, followed by towed artillery, 75-mm guns that paused to fire between the trees. Each shot pierced the night with a burst of red and yellow. He passed a convoy of ambulances coming towards him that left a long trail of blood on the road, then floated to the surface of a lake that muffled the noise of the engine and the screech of the tyres. Here he felt marvellously well for a moment, but then was buffeted by waves and the bodywork groaned and the muffled engine stopped with a hiccup. He fell asleep on the steering wheel, waking up at the first rays of the morning sun in a ploughed field, soaked in dew. The engine fired straight off, and he bumped back to the road.

Day was breaking over the Bourbonnais, with its white villages and pretty cool-smelling woods. He carried on to Lyon, where he arrived shortly before lunch after following the banks of the sluggish Saône. He was thirsty and hungry and stopped at a roadhouse by the Rhône. He was served with a jug of beaujolais, saucisson and butter, while children and gawpers surrounded the Bugatti, parked at the kerb. It had suffered during the night. Squashed mosquitoes and moths dirtied its fine blue bodywork, and its spoked wheels bore traces of of its trip across the field. But even as it was, it still looked like a thoroughbred at rest, its neck proudly tensed, its round rump with its cylindrical petrol tank. Antoine arranged for it to be washed at a garage and only then thought of himself.

His hardy woollen suit was holding out, but his soiled shirt and day-old beard did not suit the owner of a thoroughbred. He bought a shirt and changed into it at the barber’s after the barber, a small, catty man he could not bring himself to speak to, had shaved him. He was in a hurry to get started, to feel the warm wind stroking his face once more and hear the engine’s happy purring. Lyon’s deserted streets surprised him. Not a single passer-by, not a tram, the curtains all drawn and shutters shut, café terraces empty without a gloomy waiter in sight, the Rhône unfurling its bluish cold waters between banks of pebbles, Fourvière on the hill blurred in a heat haze that smothered even the sound of its bells. The Bugatti, rolling between gleaming tram tracks down cobbled streets, tried vainly to dislodge this strange torpor by the clamour of its four cylinders. Lyon was at lunch.

By mid-afternoon he had reached Valence. Another France began here, on the road out of town, in the pale green and grey of its olive trees. A violent surge of happiness filled Antoine. He knew now where he was heading. The road led all the way down to his daughter Geneviève. It had all been planned for a long time, and he hadn’t known. There was no hurry any more. He dropped his speed and drove more carefully.

On the way out of Montélimar the next morning, he bought clean underwear and filled the Bugatti with nougat. Now and again he urged it to a gallop, and the plane trees flashed past in splashes of sunlight through the foliage. The Provençal landscape, so harmonious and beautiful – the loveliest in the world – sparkled before him like a mirage with its walls of black cypresses, its roofs of curved ochre-coloured tiles, its peaceful, blessed farms and pale sky.

At Aix he stopped at a garage to have the oil changed, and a mechanic addressed him as ‘Captain’. Antoine recognised him: Charles Ventadour, tall and emaciated with a gypsy’s complexion, a driver in his company who had driven his truck all over the potholed and cratered roads of Macedonia. Aix was one place it was worth giving up some time for. He knew his destination from here, so there was no hurry.

He dined with Charles Ventadour, who reminisced about Serbia, the Turks, the roads where the Army of the Orient had got stuck, gone down with diarrhoea, shivered with malaria. He exaggerated, but in the overblown colours of his recollections there was the beauty of a shared memory, and both men suddenly felt a brotherhood so close that a friendship was born, a friendship that could never have existed in the army. After dinner they slumped in armchairs on a café terrace on the Cours Mirabeau. Why didn’t all of France live here? Shed its ambition, and let happy days roll past around a fountain bubbling with foam, watching pretty girls with passionate eyebrows and hourglass waists.

He set out again next morning, and when the sun was nearly at its highest drove through a little port full of green, lateen-rigged tartanes with crude patched sails. On the dock a few conscientious artists had set up their easels and were painting, dripping with sweat in the heat. On the road out of the village he stopped at an open-air café at the edge of a beach and got out. He was lent a black swimming costume with shoulder straps that was too big for him. A pretty girl with brown hair, pink cheeks and thick eyebrows brought him half a baguette split in two and stuffed with tomatoes, anchovies, onions and garlic, over which she drizzled olive oil from a large glass.

Sitting on the sand, for once he ate distractedly, his eyes fixed instead on the sea’s incandescent blue. Tartanes slipped across his field of view, halfway to the horizon. From time to time he turned around to look at his Bugatti, which glittered in the sun like the sea. Passers-by placed their hands on its panels, stroked it, squatted down to get a better look at its transmission, its brakes, its rear axle. Someone mentioned that the place was called Saint-Tropez. Antoine decided that when his children had all left home and he was widowed – in his mind the plan had no snags – he would sell La Sauveté and settle here. At the same moment he made the mistake of looking down at his paunchy stomach and white Celtic skin and running his fingers across his bald head, trickling with sweat. He did not like what he saw and felt. The passing years had turned him into this heavy, clumsy man, who only felt unconstrained behind the wheel of his car. The swimming costume he wore was ridiculous, and in a mirror at the café he had glimpsed his face and seen his eyes ringed with white circles from his mica goggles.

Perched on the corner of a table, the girl who had served him swung her shapely leg back and forth, exposing a tanned knee. She was talking to a boy her own age, and their singsong accents mingled. For the pleasure of seeing her up close again, and to separate her from the interloper, he asked for another ‘pan bania’ and a bottle of Var rosé. As she squatted to place the tray on the sand he saw her knee again and, looking up, found himself staring into a face full of warmth and innocence and smelling a scent of nectarine, lightly spiced with garlic. She was lovely, she was simple, she was not for him. As he left, he presented her with a big box of nougat that she accepted with exclamations of pleasure. Her name was Marie-Dévote.

The road through the Estérel wound deep into the red rock and through pine forests whose scent washed over him in great gusts. The car responded joyfully to the effort Antoine demanded from it. Its tyres squealed in the bends and it leapt up the hills and grumbled on the descents with that sweet musical sound that only a Bugatti makes. Behind it trailed aerial pools of castor oil-scented air.

Antoine drove through Cannes and Nice without stopping. They were towns for winter visitors, deserted during the summer. Beyond the port at Villefranche, signposts indicated Menton and the high corniche road. He slowed down. Night was falling on Mont Boron. At altitude and this time of evening, the Bugatti’s engine was at its best and would take off at the slightest pressure of his foot, but Antoine was no longer in any haste. In three days, time and space had lost their meaning. After he had seen Geneviève he might go on to China. This admirable machine, so precise and eager, would never develop a fault.

At La Turbie he stopped near the Trophy of Augustus to look down at the coast, where the yellow lights trembled and twinkled along the sea like a rosary. A bit further on, at Roquebrune, he noticed at the roadside a little restaurant whose terrace overlooked a slope sown thickly with plum tomato plants. The patron stood at the door in a singlet and linen trousers. An enormous, still pink scar cut across his face like a stripe, deforming his mouth. He spoke with difficulty.

Antoine sampled soupe au pistou, stuffed fleurs de courgettes and fried anchovies. The man served him with a weary casualness. In the kitchen, behind a bead curtain, two women were moving around busily: they could not be seen, but their shrill voices were audible, one young, one old. They did not appear, and once dinner was over they slipped away without passing through the restaurant. Antoine requested a digestif. The patron brought a bottle of Italian grappa and two glasses and sat down opposite him.

‘So you travel like that, eh?’ he said. ‘Leave us poor devils standing.’

Raising a hairy hand, he stroked the awful scar on his face with his fingertips, sighed, and gulped down his glassful.

‘What about you? What did you get?’

‘Oh, practically nothing. A few splinters in my right shoulder. Six months ago another piece came out. I’m not complaining.’

‘Except for hunting….’

‘Except for hunting.’

‘Where did you get to?’

‘Army of the Orient. What about you?’

‘Verdun. Douaumont. Do you like this grappa?’

‘Not bad. A bit young. I’m from Normandy, calvados is my drink.’

‘I wouldn’t say no. They used to give us a glass before we went over the top.’

They drank for a while, silent, then carefully exchanging a few words that let each place the other. Antoine would willingly have finished the bottle, but there were still a few kilometres to go, and the smashed face in front of him depressed him terribly. So many soldiers went to war with the idea of sacrificing their life, or possibly their left arm, but not one imagined that they might as easily come back with their face a pulp, and look like a monster for the rest of their days. He was conscious of his own cowardice, but without cowardice, as without lies, life was impossible. It looked as if there was a night of reminiscing ahead, scenes and stories spilling out in bulk across the tablecloth, stoked by the warmth of the grappa.

‘Were you an officer?’ the man asked, his expression wary.

Antoine felt sorry for him. He had no desire to leave a bad impression, or deepen the certain bitterness of this defeated man.

‘No,’ he said, ‘corporal. Finished as a sergeant.’

‘Like me. Stay a bit longer.’

‘I need to get to Menton.’

‘She’ll wait for you….’

‘It’s my daughter.’

‘Ah! I understand. Well, come by again one day. We don’t stick together enough. My name is Léon Cece.’

Antoine got back into the car and freewheeled down to Menton. The cicadas sang in the pine woods and tomato fields. The town was already deeply asleep. It felt like the sleep of a sick person, so respectful was the silence of the deserted streets. The fragrance of lemon trees in blossom, the dimmed glow of the streetlights were all redolent of hospitals. The houses were hidden deep in jungly gardens, walled behind high gates. Not a fishing boat moved in the dock. Antoine drove cautiously along the Promenade and eventually found a passer-by who told him the way to the clinic, a large turn-of-the-century detached house deep inside a silent park. The windows were shuttered and the doors locked. He switched off the engine, turned up the collar of his jacket, rested his head and arms on his steering wheel, and went to sleep.

Extracted from The Foundling Boy by Michel Déon (Gallic Books).

Extracted from The Foundling Boy by Michel Déon (Gallic Books).

© Editions Gallimard, 1975; English translation © Julian Evans, 2013.

Michel Déon is a member of the Académie Française and the author of more than 50 works of fiction and non-fiction. He lives in Ireland with his wife and many horses.

Julian Evans is a writer and translator from French and German. He has previously translated Michel Déon’s Where Are You Dying Tonight?

Leave a Reply