Occupied Pleasures by Tanya Habjouqa from Amber Fares on Vimeo.

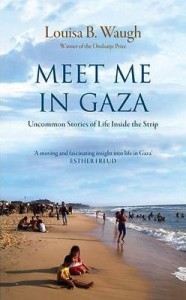

TANYA HABJOUQA won 2nd prize in the “Daily Life” category of the 2014 World Press Photo contest for her portfolio “Occupied Pleasures”, in which she set out to show Palestinians in the West Bank, Gaza and East Jerusalem demonstrating a desire not just to survive but to live. A similar spirit motivated LOUISA WAUGH, who lived on the Strip for nearly three years to write ‘Meet Me in Gaza’, which was long-listed for this year’s Dolman Travel Book Award. Here she answers one of the questions that preoccupied her when she arrived: do Gazans ever have fun?

While the fishermen fight their corner out at sea, Gazans on dry land have invaded the beaches. On these long midsummer evenings, the only breeze to be found is a ruffle of warm air down at the seashore. Makeshift cafés have sprung up along the main stretch of Gaza City beach, serving coffees and fresh juices from early afternoon until late at night. Every table is busy with families. Many other families just bring their own chairs, which they set down at the lapping sea edge, to watch their children swim, and catch the lights winking from Gazan fishing vessels in the late evenings, like stars suspended just above the waves. There are camel and donkey rides for hire, and at one end of the beach two ancient carousels creak as men spin them slowly round by hand and the small children sitting in the carved wooden seats squeal and shriek with high-pitched joy. Half a dozen makeshift lifeguard towers with look-out balconies are stationed along the beach too, where young men pose in the afternoons and play cards and smoke all night.

Other men have set up stalls selling fresh corn-on-the-cob – boiled or grilled – and hot wedges of fluffy sweet potato they bake in small portable tin stoves, then wrap in twists of paper, selling each wedge for a shekel. But the most delightful sights of all are the donkey carts that trundle along the sand, laden with buckets, spades and such an abundance of brightly coloured balloons that the whole spectacle looks as though it might just rise into the warm air thermals, donkey and all, and drift away across the shining sea. I spend many evenings down on the beach with my friends and their families, though Saida’s family tend to stay at home even on these long, sticky evenings. But one evening she calls to invite me to a beach picnic at the weekend.

‘Habibti, you remember Mata’m Haifa (Haifa Restaurant) – outside the city? We are going there for our picnic. It is more quiet than the city beach. Ummi (my mother) and Maha are coming too, and some friends. We will have fun, maybe even swim.’

Mata’m Haifa is perched above the sea, two or three miles outside Gaza City, on the southern coastal road. At Saturday lunchtime, a posse of twenty-five of us descends on the clear stretch of beach below the restaurant. I know many, but not all the women, who have brought their children with them, but not their husbands.

The women quickly shed their jilbabs, but leave the rest of their clothes, including hijabs, in place. After a splendid picnic, we lie around smoking narghile under palm-leaf umbrellas until the sun begins to cool a little. Then, in the late afternoon, most of us run into the sea fully clothed, and as we hit the waves it feels like a vast, warm bath. Saida holds my hand at first, frowning and nervous. Like most Gazan women, she cannot swim. But her sister Maha just flings herself backwards into the water, shrieking with delight. I take a swim, then float on my back for a while as the tide washes me gently back and forth. We spend hours playing in the sea with the kids, splashing and laughing. Even Hind [Saida’s mother] takes a paddle.

Afterwards, most of us loll around in the still-warm shallows, weary, salty and happy. I lounge between Saida and Hind. Saida scoops up handfuls of wet sand and gazes out to sea. She’s wearing soaked cut-off jeans and a baseball cap instead of her hijab. I watch her, wondering where she is right now. She catches my eye and smiles.

‘How is your friend?’ She says it in English, so that her mother won’t understand.

I smile back. ‘He’s fine.’

‘What about his wife?’ She holds my gaze.

‘He says the marriage is over, his wife lives in the States now …’

‘You believe him?’

‘I think so.’

She nods, then touches the inside of my arm.

‘Be careful, habibti.’

I nod back, still smiling. He is a foreigner I met a couple of months ago, an older man with a silver-washed mane of thick hair. I call him Sakhar, after the grizzled male lion in the bare-boned Gaza zoo.

Hind nudges me, wanting to be included in our conversation. She pats her big belly. ‘Leeza, I am fat,’ she says.

There’s no denying she is a big lady. I give a sympathetic nod and Hind pats my belly.

‘You were quite fat when you first came here, Leeza,’ she says cheerfully. ‘You look much better now. What exercise have you been doing?’

She looks so innocent, I am suddenly convinced that she has understood everything we’ve just said. Saida begins to giggle. I start laughing, then Hind, and the three of us lie back in the shallows until we’re all gasping for breath. I love them both so much.

As the sun begins to set, Hind leaves us to prepare herself for the Maghrib prayers, which are recited between sunset and dusk. In just a couple of weeks it will be September, and Ramadan will begin.

‘Habibti, you remember last time you and I came here together?’ says Saida.

‘Those sonic booms?’ I nod.

She nods too, then shakes her head.

Saida and I came to Mata’m Haifa for lunch a couple of months ago, just before the tahdiya [‘period of calm’]. But we had to eat our meal in a rush and leave because the Israelis started detonating sonic booms that threatened to blow out the restaurant windows.

I don’t know what to say because I don’t want to spoil our wonderful day. We sit in silence, watching the sea, drinking in its rippling vastness. I know why people loiter on the beaches in Gaza – it is because this is the only view without some kind of barrier, the only wide open space to be savoured, the only tangible sense of freedom that there is here.

Behind us, the other women are making mint tea and I can smell apple-flavoured smoke from the shisha pipes.

I hear Saida sigh, a gentle sound of evening contentment.

‘You know today is special, habibti,’ she says. ‘Because today I love Gaza.’

Extracted from Meet Me in Gaza by Louisa B Waugh (The Westbourne Press).

Extracted from Meet Me in Gaza by Louisa B Waugh (The Westbourne Press).

© Louisa B Waugh 2013.

Louisa B Waugh is a writer and human-rights advocate. She is the author of Hearing Birds Fly, an account of a year in a Mongolian village, which won the 2004 Ondaatje Prize, and Selling Olga, an investigation of human trafficking. She is currently working for a charity in Bangui, in the Central African Republic. For more about her work, see her website.

Tanya Habjouqa, born in Jordan and educated in the United States, is one of the founders of Rawiya, the first all-female photo-collective in the Middle East. She is based in East Jerusalem, where she is working on ‘personal projects that explore identity politics, occupation and subcultures of the Levant’. For more of her pictures, see her website.

Leave a Reply