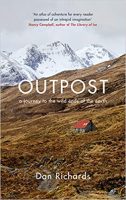

Outpost: a journey to the wild ends of the earth

By Dan Richards

(Canongate, £16.99 hardback, £9.99 paperback)

If you’re going to the wild ends of the earth, to mountain, desert and ice shelf, it’s sensible to stick with your guide. Assuming, of course, that he or she is a good one. Dan Richards earned my confidence with his first sentence: “I grew up fascinated with the polar bear pelvis in my father’s study.” *

If you’re going to the wild ends of the earth, to mountain, desert and ice shelf, it’s sensible to stick with your guide. Assuming, of course, that he or she is a good one. Dan Richards earned my confidence with his first sentence: “I grew up fascinated with the polar bear pelvis in my father’s study.” *

I was a bit surprised, then, 50 pages from the end, when he declared: “As those of you who’ve followed me through earlier chapters will know, I usually get to the places I set my heart on.” He does indeed, and I remembered the one exception up until that point, so his footnoted reminder of what he’d missed was superfluous.

I’d been enjoying his sprightly tour of what he calls “outposts” — among them the bothy, the writer’s retreat, the fire lookout tour and the lighthouse — and the thresholds they mark, both on the ground and in the head. He was a cheery and thoughtful leader, a man who could not only weather a storm but summon it powerfully again later: “every few seconds a cannonade of rubble smashed into the valley’s skip”.

His only serious failing was an addiction to footnotes. In a book that’s largely about pared-down places that enable you to reconnect with what’s important, the frequency of the notes, all elaboration and ornamentation, was a distraction. They got in the way of the flow. And I enjoyed the flow.

Richards says he’s always been drawn to simple structures: “garden sheds, hay barns, line-side shelters glimpsed from passing trains”. While researching his last book, Climbing Days, he had stints in a series of high-mountain huts, some with mod cons, some unchanged since the 1920s and ’30s, when his great-great-aunt and -uncle, Dorothea and Ivor, were mountaineering. Outpost combines his enthusiasm for those Alpine cabins — portals into and staging posts through the wilderness — with “stories of other eyries and spartan architectures on the edge”.

In Iceland, he helps renovate bothies (known there as saeluhús, houses of joy, though one is said to be a house of hauntings); in the Cairngorms, he walks between a string of them with a friend, over more than 100 miles from Rannoch to Braemar, much of it in the rain; in the Utah desert, he stays at a “Mars on Earth”, a research station in Hanksville with the address 2200 Cow Dung Road. (A note of my own: at this same station, Kate Harris, who had thought she wanted to be an astronaut, got homesick for planet Earth; she went on to cycle the Silk Road and write the acclaimed Lands of Lost Borders.)

Richards admits that some of the structures he features might have readers scratching their heads, including Shedboatshed, a Turner Prize-winning artwork by Simon Starling: a shed that was once a boat and is now a shed again. I accepted that readily: a shed that’s on the edge of something else seems entirely of a piece with the bothy. He also goes to Nageire-dō, a temple on Mount Mitoku in Japan that has been standing (or “been stood”, as he puts it) on its cliff-edge stilts for 1,300 years. His trek there, during which he’s made to join in a group chant, sounds the opposite of liberating.

Richards’s own favourite definition of outposts is “a small military camp or position at some distance from the main army”, and his book works best when he is on reconnaissance on his own or — as when he’s retracing the steps of Jack Kerouac to Desolation Peak — with a friend. In the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard, from which his father returned in 1982 with that polar bear pelvis, he denies himself a trip to the hut his father used because going there would add to the damage being done by climate change. (Others aren’t so considerate: in Iceland he hears of bothies being ransacked; in Utah, he finds plastic strewn around the research station.) Instead, he joins a group exploring less endangered areas, and finds himself amid a surfeit of snowmobiles in a place where, every spring, polar bears draw a “paparazzi circus”.

He makes the best of it, but his heart, I couldn’t help feeling, was elsewhere. I flicked back and, on page 48, found this: “The morning I flew home from Iceland, as the plane’s silhouette fell away and sped green-grey over Keflavik… I imagined a shadow self left behind, an offering to the land, now stowed unseen beneath the sea.” MK

* I’m reminded, too, of Bruce Chatwin’s opening line in In Patagonia: “In my grandmother’s dining-room there was a glass-fronted cabinet and in the cabinet a piece of skin.”

Updated February 11, 2020. This review was written at the end of April 2019 and appeared in The Daily Telegraph in print on February 8, 2020. It is also online on the Telegraph website