Your average touring cyclist, seeking respite from “the backpacker zoo” of Bangkok, wouldn’t look for it in a museum of forensic pathology. Nor would he or she, bored with “flat and whistling” Patagonia, start reciting “all the causes of peripheral neuropathy”. Stephen Fabes isn’t your average touring cyclist. He spent six years cycling round the world, covering more than 53,500 miles. He was lighting out for the territory, but he was also looking over his handlebars at “the landscape of health”.

Your average touring cyclist, seeking respite from “the backpacker zoo” of Bangkok, wouldn’t look for it in a museum of forensic pathology. Nor would he or she, bored with “flat and whistling” Patagonia, start reciting “all the causes of peripheral neuropathy”. Stephen Fabes isn’t your average touring cyclist. He spent six years cycling round the world, covering more than 53,500 miles. He was lighting out for the territory, but he was also looking over his handlebars at “the landscape of health”.

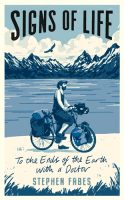

Fabes left his job as a junior doctor in London because he was “longing for a less certain future” and wanted to experience that “delectable, out-of-my-depth feeling”. As he tells it in Signs of Life (Profile Books, £18.99), he wasn’t disappointed. In Peru, a gold prospector who’d been robbed a month earlier took him for another robber and pulled a gun on him. In California, he aroused the suspicions of police who were seeking a survivalist and murder suspect. That sort of thing happens when you are rough sleeping as much as rough cycling. In China, in the state of Hunan, he was stopped by cops who wanted to examine his laptop; a laptop on which, he remembered, he had pictures of young people in Hong Kong protesting over constraints on democracy.

He has good stories, and he tells them well. He also has a gift for memorable image and pithy summary: a marmot “looks a bit like a squirrel that’s eaten three of its friends”; the Silk Road is “that intercontinental conveyor belt of religions and crossbows”. His book gains its power, though, from his realisation, once he was out on the road, that he would see more, and more deeply, if he looked at the world as a doctor.

Signs of Life isn’t quite a busman’s holiday. Fabes doesn’t stay in any one place long enough to work or volunteer, but he seeks out mobile clinics, refugee camps and war-torn hospital wards so that he can get a sense, along his way, of how that landscape of health is “moulded and eroded”. New doctors, he observes, see disease and pathology as the threats, but experience teaches that it’s the conditions for disease that are the real enemy. “On death certificates, doctors are asked to state the ‘underlying cause’ of death, and you might include… a heart condition or an infection, for example. You do not mention poverty, a rickety healthcare system or military rule, though it occurred to me that these were modes of death too.”

On his loops around the planet, the recipient wherever he paused of “little acts of kindness”, he crossed 102 international borders, but what struck him most forcefully was what the peoples of the world have in common: “When we obsess over identity and type, over categories and diagnoses, we’re in denial of our glorious complexity. When we care so deeply for lines on maps, inevitably something will sweep over them without noticing our obsession: a volcanic ash cloud, a contagious disease, weather, ideology, misinformation, and we’ll feel foolish for trusting so much in convenient fictions, for isolationism is not simply doomed, it is a fallacy.”

He pedalled home in 2016, “a mildly sad, single, debt-ridden 35-year-old, more calf muscle than man”, and is now back working in the emergency department at St Thomas’s Hospital in London. As he was putting the final touches to his manuscript in 2020, Covid-19 was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organisation and a “foreign virus” by the then president of the United States, that self-absorbed, self-basting advocate of “America first”.

Signs of Life was published last August, but I didn’t hear of it until November, when the author, having seen a piece I’d written, sent me a copy. I read it over Christmas, but, busy with a lockdown project of my own, am only getting round to mentioning it now. It’s a book that hasn’t had the attention it deserves. Over the past few days, indeed, with all the talk of “vaccine nationalism”, it has seemed, if anything even more timely.

Leave a Reply