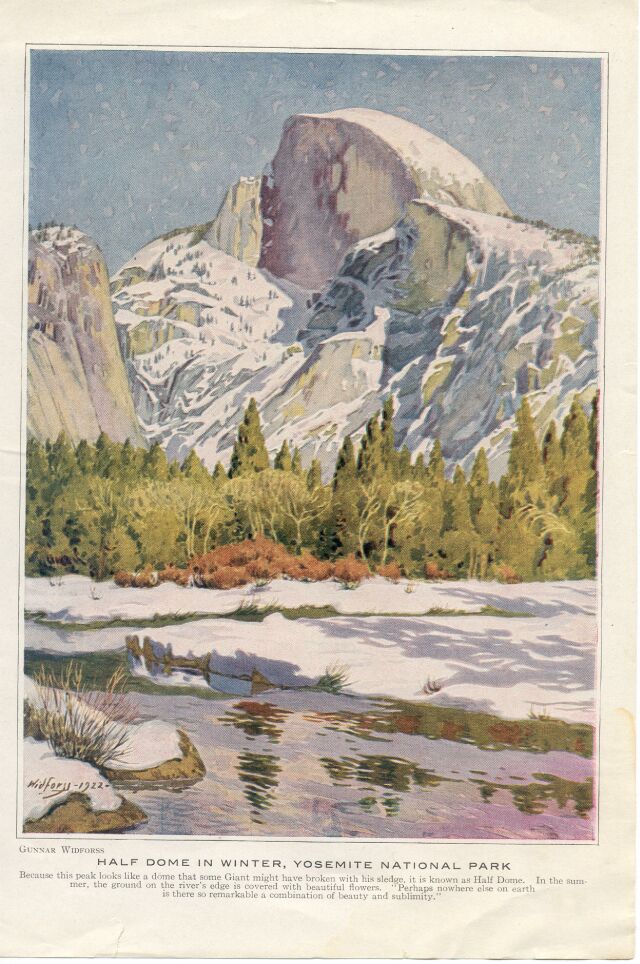

The Swedish writer FREDRIK SJÖBERG, author of the bestseller ‘The Fly Trap’, is a man who attends to what others overlook. In ‘The Art of Flight’, new in paperback from Penguin, he pays tribute to two of his countrymen who played their part in the foundation of the US National Parks Service, that great project, as he puts it, designed to ensure that ‘virgin reserves should be placed here and there throughout the country, like Sundays in a landscape of weekdays’. In this extract, he follows the travels of Gunnar Widforss, a wilderness artist virtually unknown in Sweden but revered in the United States for watercolours of places including Yosemite and the Grand Canyon

The gun-shop owner Mauritz Widforss [father of Gunnar] went to join his ancestors in the autumn of 1905. Whether his death was expected or not is now hidden in the mists of the past, nor do we know how it affected Gunnar and his plans. After just a couple of weeks, however, Gunnar was off on his travels again, this time crossing the Atlantic to New York. We can assume that he was off to seek his fortune.

The gun-shop owner Mauritz Widforss [father of Gunnar] went to join his ancestors in the autumn of 1905. Whether his death was expected or not is now hidden in the mists of the past, nor do we know how it affected Gunnar and his plans. After just a couple of weeks, however, Gunnar was off on his travels again, this time crossing the Atlantic to New York. We can assume that he was off to seek his fortune.

Exactly a hundred years later Johanna [Sjöberg’s wife] was steering the green Mustang with a sure touch northwards along the highway towards Mesquite, a flourishing small town in the desert in southern Nevada, bordering on the top-west corner of Arizona. It was a beautiful summer’s day, and everything was peace and joy. We were travelling a little too fast for my taste, but any influence I have on issues of that kind is limited. Johanna was enjoying herself and mocking the Americans for being useless Sunday drivers with a spineless and incomprehensible respect for speed limits. Until, that is, she discovered that the speedometer was graduated in miles, not in kilometres, and we too fell back into the comfortable rhythm of the traffic on Interstate 15.

I sat with binoculars on my lap. There were a number of raptors in the air along the road and some of them – they looked black – were flying with their wings at an angle you don’t see in any European species apart from the black-shouldered kite. What kind of bird was it? I thumbed through the bird book. Hardly an eagle. Buzzard, perhaps; the size was right anyway. But none of the descriptions matched, and after a while I put the question aside, hoping to see the same bird again at a lower speed. I did, too, on every day of our trip.

I mention this just to underline my total ignorance of the avian fauna of North America at the start of our journey. If you don’t know the turkey vulture, you really don’t know anything. Everything is new, including the landscape. Mountains and light. Only the burger bar in Mesquite felt familiar. The thermometer read 94° Fahrenheit in the shade. We bought five litres of water and drove on.

Long before our departure from home I had decided to learn the names of birds as far as I could. Perhaps even butterflies and certain trees, but that’s all. To try to understand the full range of the flora and fauna of a completely new and unfamiliar landscape in the course of couple of weeks is pointless, of course; just as well give up without even trying. The famous geology of the Colorado plateau was likewise included in my sphere of conscious uninterest, in spite of every book about the Grand Canyon containing at least one chapter on geology, frequently illustrated with a watercolour by Gunnar Widforss. It is difficult enough just to see all these strange rock formations and to digest the sights, but to learn the age and imaginative names of the sedimentary strata as well and to get them to stick in your memory would be as pointless as trying to photograph them without first contemplating them for months, perhaps years.

Birds, on the other hand, suit me as a provisional anchorage at least. Wherever you go, the birds of the area can be identified with the help of a bird book and a good set of binoculars. Not all of them, of course, but sufficiently many, especially for someone used to watching birds elsewhere, even if that elsewhere is on the other side of the world. I’m not claiming that this will provide the traveller with full knowledge within a few weeks, that certainly won’t happen, but with the help of birds he will be able to spell his way through the polite phrases of the landscape in more or less the same way as a linguistically interested visitor to Japan learns to say ‘Good day’ and then to order a beer.

I learned to recognise the turkey vulture, to which Linnaeus gave the beautiful name Cathartes aura, a couple of hours later, between Rockville and Springdale on the threshold of the Zion National Park, where the scenery began to be so spectacularly beautiful as to render me speechless. At dusk the very same evening we drove up through the great forests towards Grand Canyon Lodge on the North Rim, where Gunnar went for the first time in July 1923 and wrote to his dear mother: ‘I have never seen anything that can even approach this in majestic beauty!’

‘Wonderfully, indescribably beautiful, magnificent!’

But by that time it was 1905 and he still described himself in his passport as a decorative painter. Unfortunately there are few letters from these first years in the United States, but we can nevertheless follow him at a distance both in thought and in terrain. He obviously had Swedish friends in New York, among them Percy Tham, who later became consul general and who helped him to find his feet. But the reasons why he made his way to Florida remain unknown – for that is where he ended up, in Jacksonville, as a poverty-stricken fence painter with dreams of being an artist.

He wasn’t very interested in birds, as long as we exclude ostriches, which are, after all, something of a borderline case. At that time it seems to have been just about impossible to find a picture postcard in Jacksonville that depicted anything else. Gunnar sent a card showing an ostrich on the racecourse complete with reins, sulky and driver. The American ostrich industry was experiencing a veritable boom in the years around 1900, and Jacksonville was the epicentre of the craze. I presume that the initial idea had been to produce the plumes demanded by the fashion designers of the day, but it wasn’t long before the entertainment industry took over. The USA is always the USA. The whole town was like a funfair. Ostriches everywhere, and souvenir shops.

…

I SAW AN OSTRICH MYSELF ONCE, JUST ONE, FROM THE TRAIN. It happened between Mombasa and Nairobi in the days I was travelling under a false name (Mr Swellengrebel) in the company of a girl who found it very easy to cry. It was a trait that, I’m afraid to say, wasn’t improved by travelling with me.

Anyway, we had booked a sleeping compartment for two, and on that particular morning, before the girl – her name was Henny – started weeping, I was lying there looking out over the savannah that was passing by outside, when suddenly, right in the middle of everything, there was an enormous ostrich. It was over in a few seconds. This memory came back to me one day when I decided to check in my mother’s drawer to see how much I had actually revealed to her in my letters home. It turned out to be quite a lot, but far from everything.

…

APART FROM A SPELL IN ST AUGUSTINE, said to be the oldest town in North America, where he spent his time with an Indian, an Austrian ex-officer and an American missionary, Gunnar stayed in Jacksonville for the whole of the first half of 1906. A lock-out directed at painters and decorators made his already difficult situation even worse. On top of it all he had toothache. And there were too many mosquitoes. Eventually he was given a commission – to decorate the bar in the Falstaff Restaurant. After which Mr King, a well-off sawmill owner, ordered an enormous painting, 10 x 6 ft, on the Italian model. The customer was satisfied. And the artist? ‘I feel a complete humbug when I receive so much praise.’

A doctor wanted his dining room painted and an architect from Buffalo turned up with some other commissions. Things were on the move. Gunnar also sold one or two paintings at $5 apiece, but, as bad luck would have it, all his best sketches were stolen. He longed to go to California.

He moved to Brooklyn. Other Swedish painters and decorators encouraged him to go there, and there were jobs, that’s for sure, but they were hard work and the pay was useless. He got work as a paperhanger, painted signs, failed when it came to portraits, copied masterpieces from photographs and sold them cheap to survive. If it hadn’t been for games of cards with friends and the entertainments at Coney Island, he wouldn’t have lasted a day. Brooklyn was swarming with Swedes, several thousand of them, particularly from Småland and Öland, most of them Pietists, among whom there were girls who were on the lookout for a husband and had a weakness for educated Stockholmers. You had to be on your guard.

‘It would be too bad if something like that were to happen; it would mean the end of all my plans to really make something of myself eventually.’

One of the people for whom Gunnar painted signs was a Dr Borgström, a Swedish dentist in Manhattan, and, since our hero was still plagued by toothache, they developed a joint scheme. He gave a fleeting account of this business deal to his mother Blenda in a long and well-written letter in English, written perhaps as language practice. It was the late winter of 1907. An important letter, I think, which in parts expresses a fear of getting old, or of already being old: ‘I am able to learn all kinds of paintings. I only fear it is too late now. I am getting old, not in views or thoughts, but of age and that is bad enough for me.’ It’s as if some things are more easily expressed in a foreign language.

The man holding the pen was 27 years old. No age, we might think, but his dealings with his fellow-countryman in Manhattan made it easy to understand his melancholy frame of mind: the dentist had extracted virtually all his teeth and then set about restructuring and rebuilding. ‘Bridgework do they call it,’ Gunnar wrote and made the operation sound like one of the series of brilliant innovations that was making America a land of the future. The only thing he really complained about was the cocaine, the anaesthetic. It gave him such a dreadful headache.

The payment, too, was a worry that troubled him for months. The upshot was that Gunnar got new teeth in exchange for painting a portrait of Borgström’s wife – and he couldn’t paint portraits. They simply did not work. And he knew it, but it would be several years before he finally gave up trying. Nothing works in these attempts. The models look as if they are stuffed, and he was mortified and ashamed: ‘The fact is that my portrait painting is a big humbug.’

Of the few portraits I have seen, there are only three that really amount to much, and two of them – one watercolour and one in oils – not unsurprisingly depict Blenda. All the rest fail, including the self-portraits. With time, people will simply vanish from his paintings.

…

GUNNAR WIDFORSS IS TODAY COMPLETELY FORGOTTEN AT HOME. In America he is honoured as one of the great painters in his genre, whereas in Sweden even the most discerning connoisseurs have question marks written all over their faces when you mention his name. There are a number of explanations for this, one of them being, I believe, everyday bad luck. It could all have been so different. In July 1923, for example, if Gunnar’s first visit to the northern rim of the Grand Canyon had taken place just two weeks earlier than it did, he would have met a man who had a rare influence on the cultural life of Sweden, one of the influential members of the Swedish Academy and, moreover, a talented watercolourist who would probably have recognised the quality of Gunnar’s work. From personal experience this man knew the difficulties and wrote about the impossibility of painting in this very place:

For these colours are magnificent, but they are light and discreet, not intense or glaring; their effect is dreamy, rose-garden, empire style, the pink, violet or pale green dresses worn by young girls in a ballroom; they have the feel of clouds lit by the red glow of morning, and because of them the whole of this landscape seems so light and airy that it looks as if it could be blown away by the first puff of wind.

The explorer and travel writer Sven Hedin, North Rim, July 4 1923. A little piece of happy rose-scented whimsy at the end of his book about the national park and obviously composed after he had managed to forget the words he wrote in the first chapter: ‘a poet would only make himself ridiculous if he tried to sing of the Grand Canyon.’ It’s not one of Hedin’s better books. There is too much geology. And his favourite travelling companion seems to have been a thermometer. Exciting for a meteorologist, perhaps, but of little interest otherwise, we might think, even to the great author’s mother.

Because that is who he was writing for. There is a sense in which he was always doing that, but his book about the Grand Canyon, which was published in 1925, is literally a series of lightly edited letters to his ‘guardian angel’ back at home on Blasieholmen in Stockholm. ‘Not a day was allowed to end without a few pages being written to Mamma. There is no one who has followed my adventures with a keener and warmer interest than she has done. In her thoughts and in her prayers she has always been beside me along the lone and desolate roads.’

It is an irony of fate that these two mummy’s boys never had the chance to meet there, just there, just then, and feel the same dizziness in the dusk at Bright Angel Point. Sven Hedin would have loved the watercolours Gunnar had painted in the early summer in Zion and in Bryce Canyon. They were lying in the trunk of his car and very soon they would bring him his well-deserved breakthrough in Washington, D.C. But we mustn’t get ahead of ourselves.

Extracted from The Art of Flight by Fredrik Sjöberg, published in paperback by Penguin at £9.99

Extracted from The Art of Flight by Fredrik Sjöberg, published in paperback by Penguin at £9.99

© Fredrik Sjöberg, 2016

In addition to being an entomologist, Sjöberg is a literary critic, a cultural columnist and the author of several books, including The Fly Trap, which forms a trilogy with the two books included in The Art of Flight.