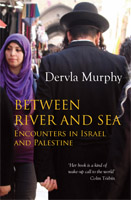

Dervla Murphy: ‘increasingly exasperated by those who pass the buck to God’. Photograph: TOM BUNNING

In the half-century since she set off to cycle from Ireland to India, Dervla Murphy, now 83, has published 24 books, all but one (her autobiography) arising from her famously frugal travels. Since 1979, when she was prompted by the Three Mile Island meltdown to write ‘Race to the Finish? The Nuclear Stakes’, her books have been what she calls “mongrels”, mixing travel with considerations of social, political and ethical problems.

Her latest, ‘Between River and Sea: Encounters in Israel and Palestine’ (published on February 19 by Eland), was bound to be one of those. It’s both an account of what she learned in the Holy Land – from ultra-orthodox rabbis, members of Hamas and everyone in between – and a passionate argument in favour of the so-called one-state solution. It was a tough book to write, not just emotionally but physically: she was stoned for her pains by Israeli and Palestinian children and had a fall that necessitated the fitting of a new hip. When she was in London in February, I met her to hear about her life on the road and as a writer, and about what could well be her last travel book. MK

MK: Moussa, the lecturer at Nablus university you met in Balata refugee camp, said he likes “reading quiet books where life is always ordinary”. But he’s going to want to read this one; what do you think he’ll make of it?

DM: I don’t know. You can’t really see your own book, you’ve been so involved in it for so long. You can’t imagine what sort of effect it’s going to have, how people are going to react.

One of the inhibitions when I was writing it was being so careful not to put anybody in danger, particularly when I was living in Balata camp [the West Bank’s most populous refugee camp, with 24,000 Palestinians in one square kilometre], because everything is so sensitive. I can’t remember whether I said it – I usually do at the beginning of a book – that names have been changed – not only personal names but often place names, but only in a way that won’t alter the meaning or the significance of the event or the story. It’s really necessary to do that.

I suppose in Balata there was the feeling of being watched all the time – and that wasn’t by the Israelis but by the local people. There are factions, political factions, there, and I knew I was being watched, who I visited [was being monitored]. No male, of course, would visit me in my room, but the women who visited – I knew that that was being noted too. So that was, as I say, an inhibiting influence.

This book was researched between 2008 and 2010, before the one on the Gaza Strip [A Month by the Sea: Encounters in Gaza, published in 2011], but it’s come out later. Why’s that?

I had tried, when I was in the West Bank and Israel, to visit Gaza, but I couldn’t get a permit to enter from Israel, and it was only in 2011, when the revolution happened in Egypt, that the gate opened so that I could enter from Egypt. I went originally thinking, “This will be the end of my book, and it will be two chapters,” because I was just going for a month. When I came back at the end of the month and read over my notes… I realised that two chapters wouldn’t do. So [my publishers] and I decided to just bring it out [a separate book on Gaza] immediately I’d finished it. Then I went back and finished that one [the new book]. So that explains the curious chronology of it all.

You say you’ve never before arrived in an unknown country “carrying so much emotional baggage, and feeling ill-at-ease rather than eagerly curious”. Was that solely because of the difficulty of trying to play honest broker in the Holy Land?

No, I suppose it was because at some level I realised what became very clear the longer I was there: that this is not a situation in which it is valid to remain neutral. Whereas in South Africa, for instance, or in the north of Ireland, for those books it was easier. Much easier in the north of Ireland. But even in South Africa it was easier to not exactly be neutral, in the sense of thinking apartheid was maybe OK, but much easier to see the Afrikaners’ point of view than I found it to see the Israelis’ – the Zionists’. A lot of my Israeli friends have said, “You should emphasise we’re talking about Zionists, not Israelis in general.”

Of all the countries I visited, that is the only one where I felt it was my actual duty as a writer not to be neutral. Not to play this game of “We’re this, we’re that; we must look at this, we must look at that.” We mustn’t. We must only look at the fact that the Palestinians are treated utterly outrageously.

At Mitzpe Ramon [a town in the Negev Desert], you say, you “realised, for the first time, that the Zionist State of Israel cannot survive”. Why not?

It’s just impossible. You cannot set up a hundred-per-cent-Jewish state. Supposing we decided we were going to set up a hundred-per-cent-Christian state, and everybody who wasn’t a Christian was going to be discriminated against. Or somebody else decided to set up a hundred-per-cent-humanist state, and everybody not humanist was going to be discriminated against. It’s not on. You don’t do it in the 21st century.

I’ve gone completely on to the side of the one-state solution. Probably Ali Abunimah [a Palestinian-American journalist who is co-founder of The Electronic Intifada] is the one who puts it best, but there are very many who feel the same way… It means the Palestinians have to give up any notion of having their own separate independent state – it’s not on – just as the Israelis have to give up having their Jewish-only state – that’s not on, either. So they both have to give up what many of them may regard as a central pillar of their ideology; it has to be sacrificed. In a sense that’s a good beginning: they both have to give up. But I don’t think that’s going to happen for a generation or two. What I really long for is more discussion of it, instead of this damned ridiculous two-state solution, which 10 years ago was being abandoned by anyone who really understood the situation.

From being a disbeliever who respected all religions, you say you’ve become anti-religious as you’ve got older: “in old age, I’m increasingly exasperated by those who pass the buck to God”. How else does the Dervla Murphy who went to the Holy Land in 2008 differ from the one who set out on her bike to India in 1962?

I suppose in the interval I’ve become so much more conscious of the fact that our Western way of life cannot actually survive – any more than Israel can as a state. We can’t go on like this, behaving as though the majority of human beings are less deserving of a decent life – I mean food, shelter, accommodation.

That’s why Cuba so appealed to me. Here was a government that as I said in my Cuba book I would not personally like to live under, as a writer and a traveller. On the other hand, the vast majority of human beings are neither writers nor travellers. They do need the very basics of life, which are denied to them in much of the world, and which Castroism gave them in Cuba. I never saw anybody there who was underfed or in rags or homeless. People are dying on the street in Dublin now, the homeless. This is outrageous.

So you’ve become more of a campaigner.

Oh, much more. I definitely didn’t start out as a campaigner. I suppose I started out with essentially the same underlying strong feelings, but they hadn’t coalesced around anything.

For your West Bank residency you bought a cheap mobile phone. Was that your first?

Yes, of course.

And have you used it since?

Very, very rarely. There’s no postal service, there’s no landline service [on the West Bank], so you have no alternative. [She writes of how, in Jaffa, a young Israeli woman in a cambio office, “being vivacious on her mobile”, took her euros without otherwise acknowledging her presence. On the same street, she “realised that not only youngsters have sacrificed their manners to the mobile. When I bought a plastic bowl in a… hardware store, the elderly Palestinian merchant left his only customer standing by the till for ten minutes while he chuckled and exclaimed in response to an invisible friend.”]

You’ve travelled with your daughter and three granddaughters –

Well, only once with the granddaughters, in Cuba.

– so you presumably wouldn’t agree with John Steinbeck, who said in Travels with Charley that “two or more people disturb the ecologic complex of an area”.

Apart from [travels with] my daughter and granddaughters, I would thoroughly and completely agree with that. I wouldn’t travel with anybody else.

Was it at all harder to research and write a book when they were with you?

Research? No, because that’s what you do at home, really; it’s not what you do on your travels. I think it cuts both ways. The best illustration of this is my Cameroon journey [in 1987] when Rachel [her daughter] was 18. I hadn’t travelled with her since she was 14 and we went to Madagascar. At 18, she was another adult. It was confirmed then that two adults is a bad idea. You get to some remote place – well, everywhere we travelled there was remote, because it was all up in the mountains, it was all villages – but you get somewhere like that and, if you’re alone, you get off to a very good start because the locals realise that you trust them, otherwise you wouldn’t be there on your own. With even two people, you’ve got somebody else to depend on. And it made a huge difference.

So in Cuba, when I went with Rachel and the grandchildren, that was just for the first month. Then I went back for three months on my own.

A huge difference in what way? Did you feel hamstrung or hindered in what you could do?

Oh, absolutely. The whole relationship with the local people was different when there were two adults. But earlier, when Rachel was a child, then it was helpful.

Because people come up and pat children on the head?

Exactly. Exactly.

There’s been concern over the past few years over how much more dangerous some places have become for solo travellers, for women travellers, particularly India. Do you think it’s more dangerous, or easier in some respects than it was?

I don’t know. I know that Rachel went off in her in-between year, her gap year, to India, for six months on her own. That was immediately before we had our trek in Cameroon. She travelled all over India alone, on trains and all the rest of it, and I was absolutely fine. But I’m not sure that I’d want one of the granddaughters to do the same thing now. So I think that answers your question.

Why not?

I think things have changed. I know this is the old fuddy-duddy way of looking at it, but I think at 83 you’re entitled to be a fuddy-duddy, aren’t you? And I really do think what the internet has brought in the way of exposure to pornography has a lot to do with the increase in violence against women. There was a really interesting programme several months ago, on the World Service, I think. It was making the point that there had been some academic study done by Indians of the correlation between the rise in cases of reported rape and the rise in the numbers of youngsters who had access to the internet and therefore to the sort of porn you get on it. I said to myself, “Well, that’s just what I thought.”

Would you have any particular advice for a young woman intent on setting off on a solo trip of the kind you’ve done? What would you say to anyone who fancied the idea of following in your tyre tracks all the way to India?

You couldn’t count the number of letters I get – emails nowadays – from youngsters who want to do precisely that.

So what do you say to them?

Well, there’s no debate about it. Sadly, you reply to them that, politically, you couldn’t do it. Imagine cycling through Afghanistan now: it’s just not on. But otherwise, to somebody wanting to do that sort of thing, but not in politically hazardous regions, I’d say go ahead and do it, of course. But looking back over 50 – let’s say it’s 52 – years since I started on the Full Tilt trip, the world, for political reasons, has become so much more violent since then.

You’ve written about your “inability” to learn languages – though it doesn’t necessarily seem to have been a hindrance. What would you say to those who argue that you can’t really get to grips with a country if you don’t speak the language?

No – it’s a real hindrance. I would completely agree with that. That’s where Colin Thubron shines: the time he spends learning a language before he goes to a country. If you haven’t got that gift – and I think I’m particularly stupid about learning languages…

You enjoyed Latin at school and that’s stuck with you. [She writes of a detained Palestinian being given no food and “only three cups of tea per diem”.]

Ah, yes, but that’s different: you’re not speaking it. So, no, one just has to make the best of it, while all the time recognising what a limitation it is. The fact that everywhere you can get by on sign language – that’s irrelevant, in a sense.

In Israel, where some people brushed off your attempts to engage them in English and snapped “Talk Hebrew!”, might it have helped to speak a little of the language?

I don’t think so, really. No.

In Wheels within Wheels [her unflinchingly honest autobiography: partly an account of what made her a writer, partly an account of the frustration she felt as a carer living “more than 16 years… in the shadow of my mother’s need”], you say: “One never writes anything of which one does not feel ashamed on seeing it in print.”

Well, I wouldn’t dream of reading anything I’ve written.

But is there a book or two of which you think, “I got pretty close there to what I was aiming for, what I wanted to say?”

Probably Gaza and the new one, yes. And I think the Rwanda one. There again, Rwanda was where I found it possible to be not exactly neutral but less sort-of decisive than I am about the Palestinian situation.

Does that make for a different sort of book?

I don’t know. I suppose it does, but… I mean in every case what you’re trying to do in your book is tell the truth. To me, the major difference with the whole Palestinian-Israeli thing is that neutrality’s not on. Have you ever come across Martin Kemp and his writings? [She summarises thus the argument of Kemp, an English psychoanalytic psychotherapist: “For long the Palestinians and their supporters have been angered and baffled by the West’s refusal to challenge Zionism, an issue Martin Kemp bravely tackles. The West feels guilty about its blatantly obvious but never openly acknowledged contribution to the Holocaust. The Zionists feel guilty about their unadmitted brutality, as they dispossessed the Palestinians by death or exile, then imposed a ruthless military occupation and organised ongoing land-grabbing. Dr Kemp sees those two guilts interacting to create an agonising tangle not amenable to standard political/diplomatic negotiations.”] What we’re dealing with here is not a political problem; it’s a psychological problem. That’s why it’s different from all the others … Well, I mean they all obviously have psychological elements and causes and undercurrents, but this is starkly a psychological problem. And until the politicians are somehow brought to recognise that, there is actually no hope of a solution.

In Wheels within Wheels, you say “something very deep-rooted and stupid” prevents you from calling out for help when you’re in a fix. Is that still true?

Yes, but I think that applies to everybody. You know, you don’t sort of yell.

Why do you think that might be? There are some people who find it easier to accept help than others, and you tell how, when you were laid up with an injured leg in Palestine, you wanted to be left alone.

It’s a sort of animal thing. Have you ever noticed how animals, when they’re feeling really ill or sore, they want to be on their own. They take themselves off into a corner and curl up.

Again in Wheels within Wheels, you say yours wasn’t “a venturesome generation” in comparison with “the young of today” [that book was published in 1979]. What about the young of the 21st century? A lot of them go off travelling but remain tied to home though social media or their parents’ insistence that they keep in touch.

I’ve no patience with them. It’s pathetic. I remember in Jaffa, in the hostel there, seeing them. In the old days, all the travellers in a hostel got together in the evening and they didn’t know one another but they were all exchanging experiences and opinions. And now… I just watched in amazement as they gathered around the six computers, and they were just queuing up silently to take their turn at the computer to communicate with the boyfriend or the parents or whoever back home. And I said to myself, “Why the hell don’t they stay at home?”

Why are they not out, first of all, talking to one another, and then out talking to the local people, interacting with them?

Actually, I find that whole thing quite disturbing. On many of my journeys, my contacts and people I met, how the whole thing developed – it was just casual encounters. Casual encounters like that, when you’re talking to the person who happens to be standing beside you in some sort of queue, don’t happen any more because they’re all plugged in to something [she sticks her fingers, as if they’re headphones, into her ears], something to do with their own individual lives, not to do with the person they happen to be standing beside.

I find it an actual disadvantage as a traveller dependent on casual acquaintances, several of whom, I won’t say many, but several of whom became friends and visited me in Ireland and invited me to visit them. Somehow we’ve become very restricted in that way, in our relationships with our fellow beings, by this stuff.

Who do you read among travel writers? You mentioned Thubron…

Ah, well, yes. I love Colin. He’s a magnificent writer. I don’t actually read travel books at all unless for the quality of the writing. I never have done, even when I was young. I wasn’t interested in other people’s travel experiences unless the writing was worth reading for its own sake.

So who, apart from Thubron, measures up?

Isabella Bird Bishop, Freya Stark… not that many, actually. Mary Kingsley, she did OK. And of course, my favourite travel book of all… Mungo Park [Travels in Africa]. That is something else. That’s real travel. And he just comes across as such an endearing character.

So there are no young travel writers, no up-and-coming writers you’d recommend?

Well, there may be, but I just haven’t come across them. I’m sure there are. On the other hand, it depends on what you call a travel writer. I often think, sadly, that none of my granddaughters can actually experience what their mother and I experienced in places like Baltistan [in the Karakoram Mountains], the High Andes in Peru, and Madagascar. In those very few decades there has been such development, such a takeover by the motor road, and the tourist industry that follows rapidly, that it just won’t be possible for them to have the same quality of experience.

Where do you want to go next?

I can’t go anywhere next because [a pause] old age has clipped my wings. At first I thought maybe it was something wrong with my heart, but it isn’t; it’s emphysema [a lung disease causing shortness of breath], which means you’re really, really restricted in what you can do physically. So I don’t think I’ll be able to get to places like North Korea that I’ve had my eye on. I think I’ll have to resign myself to sitting at home writing.

What will you write?

Well, that remains to be seen. [She has been discussing with her publishers a follow-up to Wheels within Wheels.] I mean, I couldn’t possibly stop writing.

As I did when Rachel was born, and for her first five years, it was easy to resign myself to not travelling while she was sort of establishing herself in the world, but I couldn’t resign myself to not writing.

That was when I wrote Wheels within Wheels, never intending it to be published. It was ages later Jock Murray [her then publisher] discovered that this manuscript existed because I was taking an extract out of it for the book on the north of Ireland, A Place Apart, and Jock noticed this pile of handwritten manuscript and as any publisher would took an interest in it and said, “What’s that?” and I said, “Oh, that’s just something I wrote when I couldn’t travel and Rachel was small. I just wrote it for her to read when she’s grown-up.”

And he said, “Well, I want to read it now.” And then he persuaded me that it would be a good idea to publish it. I was very resistant until Jock pointed out, he said a lot of people have been through this sort of experience of looking after a relative, a dependent relative, and he said it will help people that that’s out there. And as the years since have passed I’ve realised that he was absolutely right. The numbers of letters I got [from those] saying that they felt they were the only people who felt like that, and thanking me for it. Very, very moving, actually. But I couldn’t have written as I did if I’d been thinking of publication.

Between River and Sea: Encounters in Israel and Palestine is published at £18.99 by Eland, which also publishes Dervla Murphy’s earlier books, including Wheels within Wheels. For more about Dervla Murphy’s work, see her own website.

Between River and Sea: Encounters in Israel and Palestine is published at £18.99 by Eland, which also publishes Dervla Murphy’s earlier books, including Wheels within Wheels. For more about Dervla Murphy’s work, see her own website.

For more on Mungo Park, read Dervla Murphy’s contribution to the “Companion Volume” series published by Telegraph Travel, in which I asked writers to choose their favourite travel book.

Leave a Reply