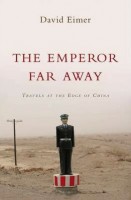

The Emperor Far Away: Travels at the edge of China

by David Eimer

(Bloomsbury)

During the Great Game, when Britain and Russia tussled for control of Central Asia, the Chini Bagh in Kashgar was the British consulate, base for the sort of men who ran the empire in the morning, collected rare butterflies in the afternoon and sipped scotch in the evening. These days it’s a bland multi-storey Chinese hotel, patronised by travellers who occasionally enliven it by smoking hash on the balconies of their rooms.

During the Great Game, when Britain and Russia tussled for control of Central Asia, the Chini Bagh in Kashgar was the British consulate, base for the sort of men who ran the empire in the morning, collected rare butterflies in the afternoon and sipped scotch in the evening. These days it’s a bland multi-storey Chinese hotel, patronised by travellers who occasionally enliven it by smoking hash on the balconies of their rooms.

When David Eimer found himself among them, the Britons decided to celebrate the place’s history. They draped a Union Jack over the balcony rails and invited passing guests to bring a bottle and join their toast to the imperial past. Then the police arrived. It wasn’t the reek of hash that bothered them; it was the evidence of separatist tendencies in the flying of the flag.

Kashgar, once a fabled stop on the Silk Road, is a dangerous place to make jokes. It lies in the far west of what is now Xinjiang, a region that is home to the Uighurs, a Muslim ethinic minority with roots in the Caucasus and Central Asia. As recent events have demonstrated — an attack in March on Kunming railway station in which 29 people died; a suicide bombing in May that killed 39 in Xinjiang’s capital, Urumqi — the Uighurs are both reluctant and restive citizens of China.

They are not the only ones. The Han Chinese account for 92 per cent of the country’s population, but at the fringes of the Chinese empire there are 100 million people who are not Han, and who chafe at Chinese rule. In a new book, The Emperor Far Away (Bloomsbury), Eimer travels through the most contentious of these borderlands, areas where a Chinese adage, “The mountains are high and the emperor far away”, still has meaning.

The journey takes him from the deserts of Xinjiang, in the far north-west, through the mountains of Tibet, to the jungle of Yunnan in the south-west and along the frontiers with North Korea and Russia. It’s a fine piece of reportage, which goes a long way to explaining why the Han are seen so often as the representatives of a colonial power, and why separatists, rather than pro-democracy campaigners, are now the greatest concern in Beijing. It’s also an eye-opening introduction for the armchair traveller to some of the least-known corners of the world.

His title, he volunteers himself, may be less than accurate in relation to Tibet and Xinjiang, where the emperor’s reach is these days inescapable. But the adage holds good in the deep south of Yunnan province, where China meets south-east Asia. There, minority peoples who for centuries have defied governments and frontiers move between countries at will, as do traffickers in drugs and girls.

Among those minorities are the Wa, former headhunters, of whom 400,000 remain in Yunnan. Another 200,000, having had no time for Mao’s China, fled into Shan State, Burma, in 1958.

What the Chinese call Wabang, or Wa State, is an unofficial country within Shan State, sandwiched between Kokang in the north and Mong La in the south, with Yunnan to the east. The United Wa State Army, known to US authorities as South-East Asia’s biggest drug-trafficking gang, has a standing force of 20,000 and a reserve of 30,000, so if the Wa fancy slipping into Yunnan, and they often do, the Chinese are not minded to get in their way.

Eimer went in the other direction. In one passage, he tells of an evening he and his fixers spent with a major in the Wa army, who not only insisted that they take him on at ping-pong, his bodyguards playing ball-boys, but that they make the most of his generous supplies of yaba, a methamphetamine that’s smoked in the way a heroin user chases the dragon.

“If it had been a stronger meth,” he says, “a Breaking Bad one, I would have thought twice about joining in. But it seemed the best way of describing what was going on in the region. The alternative would have been to write the story as a UN report — ‘The Wa grow X amount…’ — and then it becomes rather dry and boring. A night of that, even if it took a couple of days to recover, was probably worth it in terms of the book.”

Eimer, 47, was born to British parents working in the United States and grew up in London and Somerset. He toyed with being a barrister, but hated studying law, and moved into journalism, doing “the Hollywood shuffle” of celebrity interviews in the US before moving out to Asia. Having been Beijing correspondent for The Sunday Telegraph and South-East Asia correspondent for The Daily Telegraph, he is now freelance again, based in Bangkok, and hoping with The Emperor Far Away, his first book, to shape a new career as a travel writer.

When he returns to Bangkok after a publicity tour in Britain, it will be to draft a proposal for a follow-up on another country in transition, one where the generals have been easing their grip: Burma (Myanmar). It’s changing by the month, he says, and the spread of mobile phones and internet access will quicken that. “Cities such as Moulmein, which are time-capsules, looking much as they did in the 19th century, will get a high-rise skyline and apartment blocks, along with all the good things — like much better roads and a railway that works — that the country needs.”

He’s keen to get there soon, and particularly to see the far north. “The number of people who go to the Burmese Himalayas,” he says, “makes the number who go to Bhutan look like the tourist hordes descending on Bali.” MK

Leave a Reply