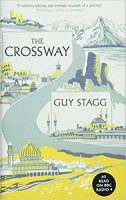

The Crossway

by Guy Stagg

(Picador, £16.99)

Guy Stagg was raised as an Anglican, stopped believing as a teenager and, by the end of his third year at university, was an atheist, “convinced that faith was a child of fear”. He declares that he’s “not much of a walker”. Why, then, did he quit his job (on the comment desk of The Daily Telegraph) in his mid-twenties and set out in 2013 to make a pilgrimage of more than 3,440 miles (5,500 km) from Canterbury via Rome and Istanbul to Jerusalem?

Guy Stagg was raised as an Anglican, stopped believing as a teenager and, by the end of his third year at university, was an atheist, “convinced that faith was a child of fear”. He declares that he’s “not much of a walker”. Why, then, did he quit his job (on the comment desk of The Daily Telegraph) in his mid-twenties and set out in 2013 to make a pilgrimage of more than 3,440 miles (5,500 km) from Canterbury via Rome and Istanbul to Jerusalem?

That’s a question he was asked by fellow pilgrims, by monks, priests and nuns, by Christians, Muslims and Jews, and even (in Lebanon) by a colonel in the secret police. He asks it himself at regular intervals in The Crossway, a debut that was blistering to write, in more ways than one, but is beautiful to read.

Before setting off, Stagg told friends he planned to explore the current crises in religion — the collapse of belief in Western Europe and the exodus of Christians from the Middle East — by taking part in an ancient ritual. In his prologue, he reveals to the reader that he hoped to mend himself after mental illness. On the road, he had got within 24 hours of Rome before he felt able to reveal that secret to two fellow walkers: “As I spoke, I realised my words had no weight, no stigma, no shame. I was afraid to share them, yet they could not hurt me.”

The Crossway is three journeys in one: outer, inner and historical. Stagg recounts his own highs and lows — both literal and metaphorical — and, in pauses from his exertions on the road, looks at the way in which pilgrimage has been used and abused since the days of Celtic Christianity, when it was first suggested that sacred travel could atone for the worst sins.

Along the way, he examines the motivations of the crusaders, who took to the road to cut down non-Christians, and the flagellants, who hacked at themselves: “When [they] stopped at a church or cathedral, the pilgrims… marched in circles, leaping to the ground to confess their sins, before kneeling in ranks, stripped to the chest, and whipping their bodies with leather thongs…”

Though he spares the whip, Stagg is far from easy on himself. Having detoured in Greece, only because he had promised a hospitable woman in Macedonia that he would take a look at the monasteries of Meteora, he forced himself to climb to one while he was unwell, spent the following night throwing up every half-hour — and then added 60 miles to his walk as “penance”.

His preoccupation with the past — his own and that of pilgrimage — never prevents him engaging with the present. There are particularly vivid passages on two events he witnessed en route: the quashing of protests in Istanbul in June 2013, the biggest challenge against the authoritarian rule of the prime minister, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan; and, two months later, the aftermath of two bomb attacks in Tripoli, the deadliest since the end of Lebanon’s civil war. What Stagg saw of the latter is recounted in a single, breathless sentence that runs over nearly two-and-a-half pages.

He had been taking a bus north — in the direction of the initial explosion. Not for the first time, he was putting himself in harm’s way, behaving like the narrator of a book on pilgrimage he was given at a monastery on Mount Athos and who, he concludes, was “at once hopeful and reckless”. In Switzerland, en route to the St Bernard Pass over the Alps to Italy, Stagg ignored signs warning him that a footbridge was dangerous and ended up in a river. A page later, he reports how he crossed railway tracks in front of a tunnel — and then heard the train coming. Even towards the end of his pilgrimage, having been warned in Lebanon to take a taxi past villages that were strongholds of Hezbollah, he refused to “skip 10 kilometres on the basis of a stranger’s prejudice”, and marched on.

At the end, it’s the kindness of strangers that lingers in the mind of both writer and reader. The Crossway is proof that you can still cross a continent in the manner of a medieval pilgrim — even an unbelieving one — and throw yourself confidently on the charity of others. I finished it certain that the author, though he tortures himself about his own worth, is hugely talented, and hoping, too, that he has retained a measure of the peace he found on the road. MK