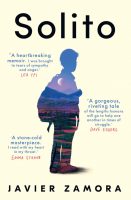

Solito

by Javier Zamora

(Oneworld, £18.99)

You’re a nine-year-old boy being raised by your grandparents and aunts in El Salvador. Your parents have fled a civil war and are living in the United States. Then they tell you on the phone that you’ll soon be taking “a trip” to join them. That trip, everybody reckons, will last two short weeks. Instead, it turns into a nine-week journey of 3,000 miles in the company of strangers. You freeze on a boat, fry in the desert, have guns pointed at you and see the adults who have been helping you get handcuffed. Imagine how that would feel…

You’re a nine-year-old boy being raised by your grandparents and aunts in El Salvador. Your parents have fled a civil war and are living in the United States. Then they tell you on the phone that you’ll soon be taking “a trip” to join them. That trip, everybody reckons, will last two short weeks. Instead, it turns into a nine-week journey of 3,000 miles in the company of strangers. You freeze on a boat, fry in the desert, have guns pointed at you and see the adults who have been helping you get handcuffed. Imagine how that would feel…

You don’t have to. In his new memoir, Javier Zamora shows you exactly how it feels. Solito is a gripping story, heart-breaking in some passages and heartening in others. It’s the finest work of non-fiction I’ve read this year.

Zamora — a graduate of the creative writing programme at New York University and a Wallace Stegner fellow at Stanford University, California — migrated through Guatemala, Mexico and the Sonora Desert in 1999. He wrote of his experience in his debut poetry collection, Unaccompanied (2017). In a recent interview in The Observer, he said he had been prompted to turn to prose and write Solito by “the weight of the trauma” that he had carried since boyhood:

“I began… during Donald Trump’s America, when everybody was talking about immigration. In 2017, when we had the Central American child crisis at the border, it seemed it was the first time Americans realised that there had been child migrants. It angered me that they didn’t realise it had been occurring for decades, and I was part of that.”

The big-picture story is that the largest number of migrants from Latin America to the United States come from Mexico and from the “northern triangle” countries of Central America: Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador. Most are running away from endemic crime, violence and a lack of work. Many who settle and prosper in the US or elsewhere send money back to their families, which in El Salvador (according to the International Monetary Fund) made up more than 25 per cent of GDP in 2021.

What Zamora wants to tell us is the small-person story. His parents send him a video player with tapes of Aladdin, Jurassic Park and the Lion King. He pictures himself playing with his Mom and Dad in a backyard that has a swimming pool and a mini football pitch. He dreams of being Superman, flying over “all the countries, over the people, towns, all the way to California, to my parents”.

Reality is vastly different. On a bus to Guatemala, and for two weeks of waiting there, Zamora has the company of his grandfather, who schools him in the route he’ll be following to “La USA” and on how “to lie better”, so that if his fake papers are questioned he can pass for a Mexican. He’s memorised his parents’ address and phone number, but, just in case he forgets, his aunt has written them, in tiny letters and numbers, along the zipper of his two pairs of trousers and inside every shirt. When there’s bad news from the coyotes (the traffickers), his grandfather distracts him with the myth of the cadejo, a dog-like spirit that will give him protection when he needs it.

His grandfather tells him, too, to stick close to Marcelo, a man from his home town. But Zamora doesn’t know Marcelo, and finds him frightening. After his grandfather waves him off on the next bus, he’s “alone, lonely, solo, solito…” The coyotes’ plans change, and he’s told he’s going to have to take a boat. He’s heard the adults talk about rumours of other boats capsizing, and — though he’s from the coastal town of La Herradura, and his father has been a fisherman — he can’t swim.

Zamora conveys powerfully what all this means to a child who’s won prizes at school but isn’t yet sure how to tie his shoelaces. But fear and trauma are only parts of his story. There are moments of fun: “It’s the most exciting thing we’ve done all trip. It’s a game. Who can make it through the most fences without getting stuck?”

Solito is a reminder, too, of how far strangers will go to help one another in times of trouble. First, there are his fellow migrants. On the boat he begins to bond with three other people, all from one Salvadoran town: a mother and daughter, Patricia (who calls herself Pati, as his own mother does) and Carla, and a man who goes by the name of Chino. When he’s cold, Patricia, Carla and Chino hug him and try to warm him up. When he’s tired and thirsty on desert walks, Chino will give him piggybacks.

Then there’s that good man on the other side — on the side of “La Migra”: the US Border Patrol. When he arrests them, he doesn’t shove them in a cell; he gives them food and drink and then, using a pair of tweezers, removes every single cactus spike from Patricia’s battered face.

Solito is peppered with Spanish words and phrases left untranslated, but whose meaning is usually clear from the context. Here and there, the prose and its rhythms remind you that what you’re reading is not the diary of the child but the work of the writer he became. On page after page, though, there’s the authentic voice of a nine-year-old boy. The coyotes, he says, have told him he’s got to act as if Patricia is his mother: “…when I have to pretend she’s my mother in public I call her ‘Mom’, and only to trick soldiers. I know who my real mom is. But it’s funny that they’re both super short, they both have big tempers, and they both like to keep things clean.”