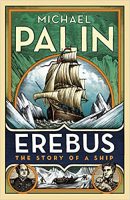

Erebus: The Story of a Ship

by Michael Palin

(Hutchinson, £20)

The founders of the Icehotel, which has been remade every winter since 1989 in the Swedish village of Jukkasjärvi, 125 miles north of the Arctic Circle, like to boast that their fusion of accommodation and art is the first of its kind in the world. Michael Palin has news for them: Britain’s Victorian polar explorers beat them to it.

The founders of the Icehotel, which has been remade every winter since 1989 in the Swedish village of Jukkasjärvi, 125 miles north of the Arctic Circle, like to boast that their fusion of accommodation and art is the first of its kind in the world. Michael Palin has news for them: Britain’s Victorian polar explorers beat them to it.

On New Year’s Eve in 1841, sailors on two ships ice-bound at the Antarctic, the Erebus and the Terror, revelled in the novelty of being able to walk between them over a frozen sea. A couple of the officers cut from the hard snow the figure of a seated woman about eight feet long, which they called their Venus de’ Medici. Then they dug into the ice and carved out not only a room but a table and a sofa. “The celebrations that followed,” Palin writes, “were unconfined. A passing penguin would have observed sailors blowing horns, beating gongs, holding pigs under their arms to make them squeal, as each ship tried to outdo the other in sheer volume of noise.”

It could be a sketch from Monty Python, except that in Erebus: The Story of a Ship the author is not in comic mode. Nicholas Crane, current president of the Royal Geographical Society, has described Palin, one of his predecessors, as “the world’s most appealing practitioner of geographical curiosity”; it’s that curiosity which drives his stirring new book.

Palin was asked five years ago to speak at the Athenaeum in London about a member of the club, living or dead. He chose Joseph Hooker, who, Palin knew from his own travels for television in Brazil, had been an acquisitive director in the 19th century of the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew. Then he discovered (“a revelation”) that Hooker, while in his twenties, had served as assistant surgeon and botanist on the Erebus, a sailing ship whose crew spent 18 months in Antarctica and returned to tell the tale — “the sort of extraordinary achievement that one would assume we would still be celebrating”.

We might well be, had success at one Pole not been overshadowed by disaster at another. In 1846, while Sir John Franklin was commanding Erebus and Terror in their search for the Northwest Passage, both ships, with all 129 men, vanished into the white. An expedition that began with imperial confidence probably ended — we know now — in cannibalism.

Before reading Palin’s book, I was well aware of the disaster, and of how, largely thanks to the campaigning and cajoling of Franklin’s wife, 30 searches by sea and land were dispatched in the decade after the ships’ disappearance. I had followed Franklin not only through the pages of Andrew Lambert’s absorbing biography of 2009 but into the Northwest Passage. The wreck of the Erebus was found in Canadian waters in 2014; two years later, I joined an ice-breaker on a “Finding Franklin” trip organised by the company One Ocean Expeditions, a tourist outing in the wake of trail-blazers. While we were at sea, a team from Parks Canada was looking for the Terror; the following month, they found her.

I knew little, though, about the earlier days of the Erebus, a 100-foot “bomb ship” that never fired its mortars in anger but, in Palin’s phrase, explored a post-Waterloo world “in which heroes fought the elements, not the enemy”. Under the leadership of James Clark Ross (who had already planted the British flag at the North Magnetic Pole), she was part of expeditions that proved an Antarctic continent existed and, in 1842, went further south than any explorers would do for the next 60 years.

Palin gives ship, shipbuilders and sailors their dues, combining diligent work in the archives with passages on his own travels to places the Erebus called at, including Tasmania, the Falkland Islands and (with One Ocean Expeditions) the Canadian Arctic. For the early part of the story, he draws extensively on the diaries of Hooker (one of the ice carvers of 1841) and another naturalist, Robert McCormick, who rarely saw a bird without shooting it for his collection. But then those were days, Palin reminds us, when explorers “couldn’t see the wood for the price of timber”.

His account is written in crisp, unshowy prose, though now and again (“pride before a fall”; “poisoned chalice”) it slips into language as whiskery as some of those intrepid Victorians. Only once, when I read of Palin’s evening on an ice-breaker “singing lustily” the Stan Rogers song “Northwest Passage”, did I find myself thinking of Monty Python and lumberjacks. MK

This review appeared in The Daily Telegraph on September 29, 2018