I’m hoping to visit Arizona soon to write a travel piece. I’ve been doing background reading, buying guides and other books and making contact with people whose brains I would like to pick — all online. I couldn’t do that in the mid-1990s when I visited the Eastern Shore, that broad peninsula cut off from western Maryland by the great curve of the Chesapeake Bay. The Daily Telegraph, for which I was then working, had started what it called the “Electronic Telegraph” (on November 15, 1994), but its small staff was still separate from the print team, producing a publication that, initially, was updated just once a day. When my piece on the Chesapeake Bay appeared in print, on March 4, 1995, it was accompanied by mentions of the airline and tour operator with which I travelled, the hotel where I stayed and the tourist board that helped me on the ground. I gave telephone numbers for all of them — but no websites. Few organisations then had websites, and few readers — while access was still being charged by the minute — were minded to go online.

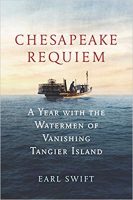

In those days, I did much of my most useful background reading when I arrived, following a swift scouring of the shelves of one or two local bookshops. Which is how I found Watermen by Randall S Peffer (Johns Hopkins University Press), a vivid and salty account of a year Peffer spent with the fishermen of Tilghman Island, harvesting the Chesapeake’s oysters, crabs, fish and waterfowl. If you’re heading to the Chesapeake Bay (and even if you’re not), I’d still thoroughly recommend it. But first, maybe, I’d urge you to buy a more recent, more topical book: Chesapeake Requiem by Earl Swift, which was published last month in the United States by Dey Street, an imprint of HarperCollins, and which I have just started reading. It promises to be an affectionate but inquiring portrait of a singular place.

Swift, a long-time reporter for the Virginian-Pilot, lived full-time for a while on Tangier Island, which sits dead centre at the Chesapeake’s broadest point, “at the mercy of nature’s wildest whims”. Those whims are a large part of his story, which he researched over nearly two years. The inhabitants of Tangier have made their living for generations from crabs and oysters. But the very water that sustains their community — one of 470 conservative and deeply religious people — is also slowly erasing it. A study published in 2015 by Nature suggested that the island, which has lost two thirds of its land since 1850, could become the first American town to fall victim to the rising sea levels brought about by climate change. Donald Trump, who is hugely popular on Tangier, has said there is no reason to worry…

Leave a Reply