After a warning early in April that I was about to exceed the limit for my email inbox, I did some serious pruning. Among the survivors was a press release I’d have spiked in an average year, but 2021 is far from average, and the press release seems indicative of our times. It’s from a PR firm representing an insurer, and arrived in February, when there was snow and ice on the roads in Britain. In an average year, an insurer would be offering tips on how to drive safely on the Continent. This time, it’s telling me “How to drive safely to your vaccine appointment”.

I’m a travel writer who hasn’t researched a travel piece since the end of 2019. I’m a journalist who hasn’t done any paid work since November 2020. Early on in the pandemic, I even found myself thinking that it would be good to have a reason to fill in one of those risk-assessment forms designed to satisfy insurers; the sort of form where I’m reminded: “When using buses or trains [journalists] will check the front of the vehicle for the journey information to ensure they do not board the wrong one.” So when the Telegraph asked me if I’d like to interview Paul Theroux, albeit online, I said yes immediately.

Theroux had recently turned 80, but was still behaving like a writer keen to make a name for himself. Last Train to Zona Verde, which he published in 2013, may have been, as the subtitle has it, his “ultimate African safari”, but it wasn’t his last travel book. Since then, he had driven through the southern US for Deep South and through Mexico for On the Plain of Snakes; in between, he delivered an essay collection, Figures in a Landscape, on people and places.

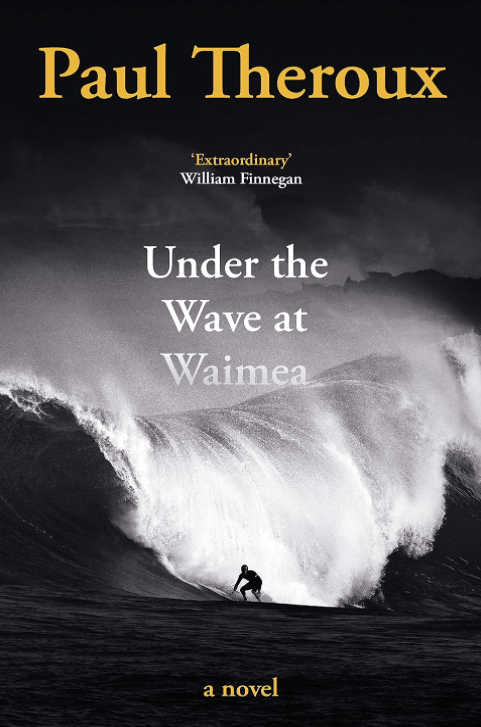

His latest book, Under the Wave at Waimea, was his 56th. It’s a novel about a man who has done some travelling himself, but who never reads: Joe Sharkey, a big-wave surfer on the Hawaiian island of Oahu, who is struggling to come to terms with the dimming of fame and the advance of age. It’s a book about the joys of surfing (“a rush, a feeling, a dance”), about living a lie, and about the unseen life of Hawaii.

Our Zoom “conference” was set up by a publicist based in Atlanta. Theroux was in Hawaii; I was in suburban Surrey. I’d thought we might have half an hour or 45 minutes, but we ended up chatting for an hour and a half. Throughout, there wasn’t a hitch or a glitch; picture and sound were perfect. (Though I did have an anxious moment at the end when I wasn’t sure that the session had been recorded.)

I was reminded of conferences I’d covered as a reporter in the days before mobiles, when I’d emerge from the proceedings and rush to find a phone box. I’d call the paper, be put through to copy-takers, and start dictating. Meanwhile, the wind would be howling through a gap round the door or a broken window pane (“the windy phone-box syndrome”, as one of my old colleagues put it), the copy-taker would be asking me to speak up or slow down, and a member of the public, wanting to use the same phone, would be banging on the glass and asking whether I was planning to camp there all day.

Though the peg for the interview was a novel, I was writing a piece for the travel pages, so we talked not just about fiction but about Theroux’s home in Hawaii, travel and travel writing, and how he saw the post-pandemic future.

In one passage in the book, Sharkey’s new girlfriend and saviour, an English nurse, notes that he has been everywhere, and he responds by telling her he is now “cured of travel”. What about Theroux, I wondered; was he similarly cured, or were there places he still wanted to visit, to write about?

He told me: “It would be a long bucket list. I especially want to go back to places that I’ve lived in. It’s one way of seeing the way the world is trending; the way the world is or isn’t improving…”

I’ve been asking myself the same question. Travelling with a notebook has been part of my work since the mid-1990s. It became a bigger part from 2014, when I quit a staff job to go freelance. I spent a few years pinballing around the world, writing about places from Welsh Patagonia to Siberia. When I gave up flying for work in 2019, I expected that I’d carry on travelling, but doing it more slowly, shorter-haul, taking boats and trains. Then came the pandemic.

I’m one of the lucky ones: late on in my journalistic career, still scribbling because I want to keep my hand in rather than because I absolutely have to. I thought I’d miss being on the road, but I haven’t. Maybe I’m cured — or maybe I’m finally acknowledging that I’ve already done more than my fair share of travelling. There were places I thought I’d return to, to see how they’ve changed, but my decision to be a flight-free traveller (at least when working) has since put them out of reach. One is Cuba, which will remain fixed in the mind as I found it on a trip in 1996.

* * *

The taxman treated me to my first Cuban coffee. “Here,” he said, pressing a coin in my hand, “pay with this.” When I had collected my thimbleful, he waved me towards his table. ‘I am Ramón,” he said, “and this is my colleague, Isabel. We are economists, working in the local tax office.”

Ramón had saved me from financial embarrassment. Having seen a scribbled “$1” symbol on a card by the café till, I had been about to hand over a dollar, forgetting that the same symbol was used for the Cuban peso. “The current rate is 21 pesos to the dollar,” Ramón said. “You were being very generous.”

Not so generous, though, as he had been. His gesture, in a country where the average monthly wage was less than the equivalent of US$20, made me think well not only of him but, once again, of his people. For after two days in Cuba, I had been growing tetchy with Cubans.

I loved Havana. I loved its streets with their overloaded Chinese bikes and lumbering American cars. I loved its shady squares where the locals yell out the baseball results and swap apartments. I loved every peeling, pitted, pastel bit of it. The only problem was the jineteros.

A jinetero is a hustler, someone intent on parting tourists and their money, and in Havana and Santiago, Cuba’s second city, jineteros were multiplying. Hunger for dollars was largely responsible. Before 1993, mere possession of this currency would have earned a Cuban a jail term; some were determined to make up for lost time.

I rarely crossed a road, and never a park, without hearing the words “Hello, amigo, where you from?” Occasionally, the line was delivered by a genuinely sociable man or woman. More often it was the prelude to an offer of cigars or rum, or an invitation to stay in a casa particular (a private house with rooms for rent) or meet a woman of great beauty but modest price.

I had read that Cuba, throttled by a US blockade, was experimenting with el capitalismo frío, cold capitalism. I hadn’t expected that tourism would have warmed things up so quickly. The thud of the pile-driver, sinking the foundations for hotels, sometimes drowned completely the softer rhythms from doors and windows, the son and salsa spawned by that love affair between African drums and Spanish guitar.

In some respects the old city was much as I expected. Here and there stood neoclassical colonial mansions resplendent in new paint supplied by Unesco (Old Havana is a World Heritage Site). But everywhere else was faded finery, years of neglect achieving those subtle hues for which interior designers charge a fortune in Miami. Buckets came down from balconies on ropes, returning scarcely any heavier with the fruits of a day’s queuing. Shark-finned Plymouths and Studebakers rolled up to junctions, revving loudly, as if their drivers feared that an engine paused might be an engine permanently stilled. And everywhere there were bikes: bikes built as rickshaws, bikes built for one but which here carried three, and bikes with no lights that constituted probably the greatest night-time danger to a wandering visitor.

At the Museum of the Revolution, in the shadow of a tank, schoolchildren queued alongside conscripts. On the hoardings, the banners still read Venceremos (We shall overcome). But I kept thinking it would be a funny old victory if it were bought with dollars; dollars spent in tourist hotels on Wild Turkey and Jim Beam’s whiskey, on Winston, Salem and Marlboro cigarettes; dollars for which my tour company’s rep had temporarily renounced biochemistry. In the “socialist state of workers independent and sovereign”, some had long been more equal than others, but dollars were widening the gap.

I heard of a 17-year-old prostitute who had a 60-year-old Spanish sugar-daddy visiting her three times a year. On learning that people had to collect water on alternate days from a well in her street, he offered to pay for the supply to be plumbed directly to all homes in her building. “No,” she said. “Just fix it for me. Let the rest pay for themselves.” So the other residents were squirrelling away what they could. One told me that in six months his family had saved US$13 — in coins.

This was the lot of the majority of Habaneros, who were too busy hunting the evening meal to nag tourists. During my visit, rations were: a portion of bread per person per day; 1lb of fish every two weeks; and 6lb of rice, 6lb of sugar and less than 1lb of black beans a month. Mike, an American tourist, told me: “I’m ashamed when I see what the people have to live on, and I feel partly responsible.” We had met in the Casa Científico, once a presidential residence and more recently a hotel for visiting scientists. In its wood-panelled dining room, we sat on chairs of the kind usually roped off in museums, and drank from glasses labelled Secretaria Ejecutiva para Asuntas Nucleares (Executive Secretariat for Nuclear Affairs). Mike had feared that he would be blamed personally for the blockade, but had been delighted by the warmth of the local people; he was planning to come back with his wife.

Felix and Carmen, a middle-aged Swiss couple staying in the hotel, had no intention of returning. Having sold everything in Zurich the year before, they had gone to Central America with a view to opening a small business. They had been to Costa Rica, Guatemala and Honduras, but nowhere, they said, had they been pestered so much by hustlers and beggars as in Cuba. They were tired of being valued only for their dollars. “There are,” Carmen concluded bitterly, “no true friends here.”

I, too, had been surprised by the begging, and by the muttering against the government that I heard after only the briefest acquaintance with everyone from young rickshaw cyclists to whiskered old women. Thinking that such things might be distorted in Havana by the tourist trade, I decided to head for Santiago, at the other end of the island, to see how socialismo was faring there. Santagüeros were renowned for their loyalty to Fidel Castro.

With its horse-drawn buggies and cattle-truck buses, Santiago had the air of a market town rather than a city. On its eastern edge, I strolled along leafy avenues of substantial villas, some converted to schools or restaurants, others the homes of bureaucrats. For a while, I didn’t feel like a tourist.

In the centre, however, the hustlers were more of a nuisance than in Havana. The local folk-music centre, the Casa de la Trova, provided a respite. I went intending to stay half an hour and was still there 90 minutes later, mesmerised by the sad songs of two old balladeers. In the concert hall, scarcely big enough to garage four of those shark-finned cars, I was for much of the time the only non-Cuban in an appreciative audience.

Later, in the recently restored Casa Grande hotel, I saw musicians playing equally well, but to the backs of two men doing a deal and a group of tourists loudly planning their evening. How should I spend my own evening? A young woman who approached me in the lobby of my hotel had a suggestion. She told me she was a nurse and offered to be my paid companion. I told her I was married. “But señor, that is no problem. You can have a wife in Inglaterra and a chica in Cuba.” In the complaints book at reception, a visitor had written in French: “Why is it that you let any fair-skinned people into the hotel, but no black people apart from prostitutes?”

I discussed all this later with a grey-bearded man who had answered my bumbling Spanish with fluent English. He turned out to be a physicist who had been educated in California. “At one time,” he said, “I knew more words in English than in Spanish. These days I rarely practise. I don’t want people to think I am trying to sell them something.”

That was the most unfortunate side-effect of the rise of the jineteros. Tourists came to regard every approaching Cuban as they would a double-glazing salesman. The great majority of Cubans, who wanted only conversation and friendship, extended a hand and often found it slapped.

In Havana, I had almost given Jorge (not his real name) the brush-off. He approached me in the street, in the manner but not with the motive of a jinetero. He was in the final year of an English degree and invited me to dinner at his home so he could practise the language. The following evening I climbed the crumbling steps to the second floor of a building in the city centre, lighting my way with a torch. Jorge’s father, mother, wife, son and daughter and extended family were settling down in front of a Brazilian soap opera on the TV and I was briefly introduced before being taken next door. The apartment was cramped — bedroom, living room and kitchen running along a corridor barely 20 feet long — but spotless. A tapestry of a bullfight hung on a wall; dolls in Native American dress sat on the shelves.

As we ate our omelette, rice, beans and tomato, Jorge said: “A few years ago I couldn’t have invited you home because we were starving. But now, although we don’t have meat, we do have the beans and the protein.”

I returned the compliment on the evening I got back from Santiago, taking Jorge to a paladar, a family-run restaurant, one of those valves through which the government had recently allowed the steam of private enterprise to escape. Behind its heavy door, we enjoyed a feast: fish, black beans, rice and chips, with beer — for about the equivalent of £13 for two.

The owner complained that the authorities were killing her business with new taxes. Later her husband, a dapper man with swept-back grey hair, appeared in the room. As Jorge interpreted, the man told me, among other things, that he was injured and could no longer work. What had he done before, I asked. He answered: “No one asks what the prisoner does, and I am a prisoner. Cuba is a prison of the mind.” Right at that moment, Castro appeared on a TV screen behind him, wagging an admonishing finger.

There was a touch of theatre about this, but none in the incident I witnessed the next day. It was my last in the city, and Jorge was accompanying me to an art gallery. As we walked past my hotel, the doorman told him: “The police are round the corner with a van. Go back into the hotel with your friend and leave by the back door.”

Jorge, clearly terrified, told me that he had friends who had been interrogated simply for spending “too long” with tourists. Our visit to the gallery would have to be cancelled. He was sorry. He took from his bag an LP by the salsa star Isaac Delgado and handed it to me. “I know someone who knows Delgado, so I haven’t paid for it,” he said. “And I’m not selling it — it’s a gift.”

* * *

In preparation for my interview with Paul Theroux, as well as reading his new novel, I dipped again into some of his back catalogue, including The Tao of Travel (a compendium of excerpts from books that have shaped him, as a reader and a traveller) and The Kingdom by the Sea. The latter is his account of a trip round the coast of Britain in 1982, in the summer of the Falklands War, after 11 years living as an American in London. In his fourth chapter, he writes about hooking up in “the monotonous frenzy of Brighton” with his friend Jonathan Raban. While Theroux was travelling by train and on foot, Raban (in a journey he would recount in Coasting) was circling the country in a 32-foot ketch, intent on getting the measure of home by putting into its ports as a visitor. After their meeting, Theroux went on by train to Bognor Regis, stopping off en route in Worthing. He sums up the town like this: “It was a breezy, villagey place, with tree-lined streets, and like the folks who lived in it, Worthing was a little old, and a little lame, and a little stout, but it still had sparkle.”

I hoped he was right. Teri and I would soon be moving there, exchanging the squawks of ring-necked parakeets for the mewing of herring gulls.

Leave a Reply