In that old-normal world of a few years ago, when family came to stay, my sister Anne was over from Northern Ireland. She was looking through our kitchen window when her eye was caught by a flash of lime-green. The flash hit the pear tree, and resolved into a bird with a strikingly green body and a red beak and blueish tail. “Michael,” Anne asked, “what on earth is that bird in your garden?”

“Parakeet,” I told her. “When we moved here in the 1980s, we’d see the odd one in the park. Now they’re everywhere, and we get them in the garden all the time. You often see a big flock going over — though you usually hear the squawking before you see them. I’ve heard they escaped from an aviary somewhere and then began to breed.”

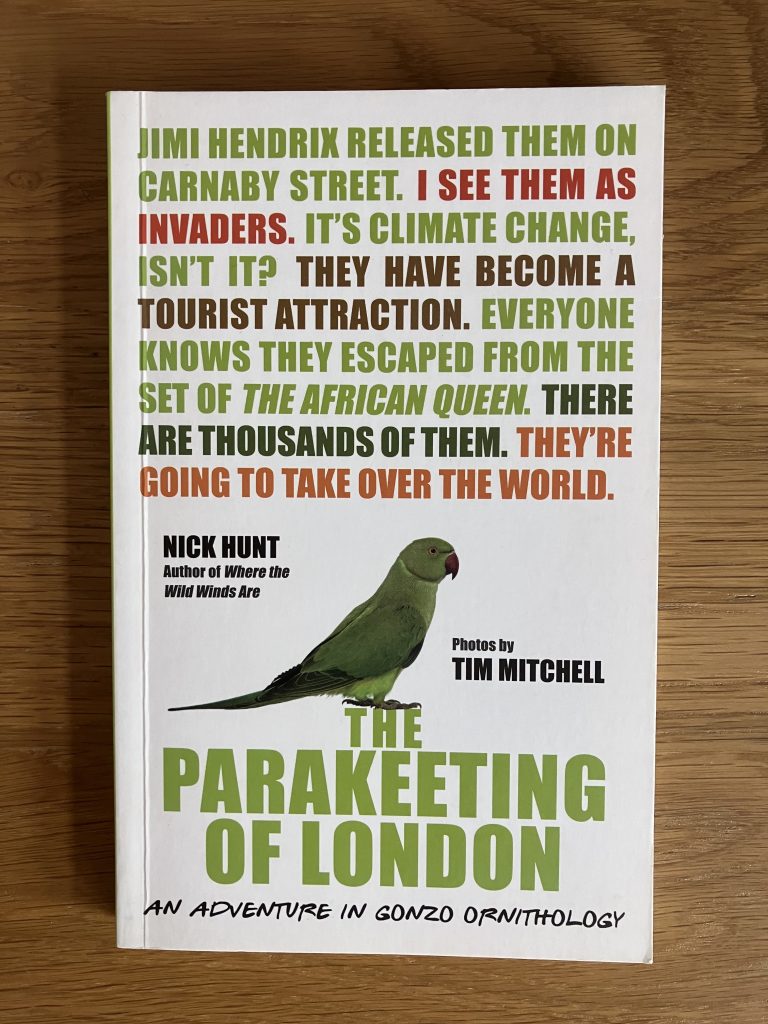

That was as much as I knew then. But just as the recent limiting of my horizons has made me more appreciative of Nonsuch and Shadbolt Parks, so it has also prompted me to find out a little more about the parakeets. A few months ago, I ordered a copy of The Parakeeting of London*, a collaboration between the writer Nick Hunt (author of the travel books Walking the Woods and the Water and Where the Wild Winds Are) and the photographer Tim Mitchell. The morning it arrived in the post, I took it into the kitchen and, after unwrapping it and washing my hands, happened to look through the window. At the top of the sycamore beyond the fence at the end of our garden was… a parakeet.

Or, as I now know, a ring-necked, or rose-ringed parakeet, Psittacula krameri. (The adult male has a pink-and-black neck ring; the hen and immature birds of both sexes have no ring or at most a shadowy one.) It’s a species of small parrot whose native range extends across South Asia and Central Africa. The earliest reported sightings in London were in the 1890s, but the population exploded in the 21st century. Having colonised the green spaces of the capital, parakeets spread into the Home Counties and have reached as far north as the Cairngorms.** How did it happen? No one knows.

One story has it that a flock of birds was freed (or escaped) during the filming in 1951 of The African Queen, that story in which a prim and proper spinster and a gin-swilling steamer captain end up in the same boat. Another suggests that a breeding pair was let loose in Carnaby Street in the 1960s by Jimi Hendrix. There are all sorts of theories, explanations and legends, which Hunt and Mitchell heard recounted and embroidered as they made their way through places in London that the birds are known to frequent: parks, gardens, cemeteries, woodlands. Hunt asked passersby what they knew and thought about parakeets, and recorded their answers. Mitchell took pictures of people, places and, occasionally, parakeets — using a standard lens, because the view that offers is closest to the one we all have of the birds through the human eye. The result is a book of anthropology as much as ornithology; not only about these new avian residents of London, but about how the birds are variously seen by the humans: as a tropical tonic, as invaders, as a squawking indicator of climate change.

There’s a word, too, on what the parakeets have given the authors: “re-enchantment”: “An environment’s ability to surprise,” Hunt writes, “diminishes in direct proportion to the time you spend in it; it can seem there is nothing left to explore; nothing new to discover. Sometimes it takes a visitor to open your eyes again — to raise your vision from the paving stones… and the parakeets have had that effect. They have given us back our enchantment in this extraordinary city.”

Their little book, which I’ve been carrying lately on walks under parakeet flight paths on my patch of suburban Surrey, has had a similar effect on me. I’m not a naturalist, not a birder. But I do enjoy reading people who are. I agree with Simon Barnes, who says in How to be a bad birdwatcher *** that “Looking at birds is a key: it opens doors, and if you choose to go through them you find you enjoy life more and understand life better.” Following birdwatchers, as they have followed birds, has taken me to places I would never otherwise have seen.

* * *

Down came the big birds over the reed beds: marsh harrier, grey heron, great cormorant, and then a Boeing in the orange-and-white plumage of easyJet. Only a fraction of what’s on the move over Barcelona pays any heed to the directions of air-traffic control; and only a fraction of the migrants passing through on their way south have to fret about passports, visas or security.

I had previously been to Barcelona three times, but it wasn’t until October 2011 that I realised that the “Llobregat” that lends its name to the airport of El Prat de Llobregat is a river. It rises in the Pyrenees, enters the Mediterranean just south of Barcelona, and on its way irrigates a sizeable coastal plain. On that plain are several nature reserves, including one of 464 acres on the edge of the airport.

The Espai Natural del Remolar-Filipines is not only a little world of its own; it has little worlds within it: marsh, pool, pine grove, riverside, even a beach. It’s a haven for aquatic birds — and for aircraft passengers with time on their hands who fancy a breath of fresh air.

Our visit was shorter than most. We had arrived at the airport before noon on a Saturday with a few hours to kill after a week’s birdwatching in the delta of the Ebro River in southern Catalonia. Having driven to the perimeter of the reserve, we found a barrier down but unlocked, so we raised it and drove into the car park. There we were told that the car park wasn’t open at weekends because it got too congested (there had been no mention of that on the notices outside); we would have to drive out again, park a mile-and-a-quarter beyond the perimeter and walk back. Julian, our guide, who had seen the reserve before, volunteered to drive out and stay with the minibus while the other four of us had a wander around. We would be deprived of his expertise, and his unerring ability to identify a bird as soon as someone had spotted it, but we would at least have an hour-or-so in the reserve before flying home. We had hardly stepped on to the gravel path when we were greeted by the explosive, metallic call of a Cetti’s warbler, a bird the RSPB describes as “small, rather nondescript” and “difficult to see”. So it was for me, though my companions, Mike, Jane and Deirdre, seasoned birders all, managed to separate it from its surroundings.

Through the screens to either side of the path, I had less trouble seeing mallard, gadwall, great crested grebe and dabchick, and what we took for turtles but which Julian told us later were Spanish terrapins.

The reserve had several well-designed hides. In one we found parents with excited young children, who could spot quite a lot with the naked eye, and men with seriously long lenses. The latter would have been hoping for a close-up of one of the area’s less frequent visitors, perhaps the great bittern, more often heard booming than seen, or the Temminck’s stint, a greyish-brown wader with a white belly.

Thanks to Jane’s left-a-bit, right-a-bit guidance, I got a good view of the serin, a short-billed yellow finch, pecking its way among mudflats with the control tower in the background. It’s not a bird I’m likely to see in Britain, where it’s recorded only a few times a year.

Back outside, scanning trees from the path, Mike alerted us to the presence of a kestrel and then a woodpecker behaving in contradiction of the field guides. Unlike its British cousin, they say, the Iberian green woodpecker rarely drums on trees and spends a lot of time on the ground in pursuit of ants. This one, however, was at the top of a tree, its red crown and black-enclosed white eye standing out (once I’d been told where to look for them) against grey bark.

Would we have heard it if it had been drumming? Probably. For there were quiet moments between the take-off and landing of jets; moments that made us forget where we were.

* * *

I’d joined the birding trip to the Ebro delta partly because it offered an opportunity to cover a lot of ground in a few days and introduce myself to an area I had plans to return to on my own.

The Ebro — which inspired in Don Quixote “a thousand amorous thoughts” — is the longest river flowing wholly within Spain; the river, indeed, that gave its name to the whole Iberian peninsula. It rises in the mountains of Cantabria, a last stronghold of the brown bear, and — some 600 miles later — enters the Mediterranean to the south of Barcelona, where its delta is not only a giant rice paddy and a haven for wading birds, but also sometimes a hiding place for drug smugglers. In between, the river flows through seven autonomous communities, or regions: Cantabria, Castile and Leon, La Rioja, the Basque Country, Navarre, Aragón and Catalonia. Thanks to a long-distance footpath, the GR (Gran Recorrido) 99, you can walk alongside it from source to mouth, which is what I was proposing to do. I had an idea for a book, in which I’d follow one waterway through the mini-nations that comprise modern Spain. I filled a shelf with background reading: novels, nature, history, as well as guidebooks such as Camino Natural del Ebro: GR 99. My own book never happened: a publisher who was keen on the idea lost his job, and then the whole thing, for various reasons, fizzled out. I did, though, see quite a lot of the Ebro while writing travel pieces that furthered my research, and I vividly remember my introduction to the delta.

* * *

The tractor splashed across the stubble of a paddy, its rear end a blur of flapping wings and pecking beaks. Behind it were grey herons, little egrets, lapwings and hundreds of gulls — yellow-legged, lesser black-backed and Audouin’s, one of the most endangered gulls in the world. Here, in one image, was the Ebro delta: a water-land of rice and birds.

We had arrived that October afternoon, motoring down in two hours from Barcelona airport to this southern tip of Catalonia. Our hotel was in the town of Deltebre, right in the middle of the delta, perfectly placed for forays to riverine reserves, beaches and, farther afield, to the “drylands” of Alfés and the mountains.

Not that we needed to go far to see birds. We had barely dropped our bags when two of our party, Mike and Jane, called us in to enjoy what they could see on a branch right outside their window: the electric-blue and orange of a kingfisher.

Now we were exploring in and around a private lagoon, Canal Vell, which is just off the main road between Deltebre and the coastal town of Riumar. I can say that with confidence because I have a guidebook to the delta with a map in front of me, but I couldn’t have done at the time. The delta, an area of 124 square miles, of which 75 per cent is given over to rice fields, is a confusing place in which to travel, a network of lakes and watery fields where one lake, one field, looks much like another.

I can say with confidence, too, having checked a trip report, that as well as herons, eagles, gulls and marsh harriers, we spotted greenshank; ruff, wood, green and common sandpipers; common snipe; and ringed plovers. At least, my companions did, being a lot better than I am at separating birds from their surroundings and then identifying them.

I was with Julian Sykes, a Yorkshireman based in Oliva, Valencia, and then running his own wildlife-holidays company, and four of his customers. Mike and Jane were retired, from aviation and computing, respectively; Deirdre, a piano teacher, seemed to be defying retirement, whereas Elizabeth, a former nursery nurse, had embraced it early. All of them were experienced birders, and Julian clearly had two pairs of eyes, for he had no trouble watching roads and reed beds at the same time.

I was blind by comparison, but I didn’t need experience or the Collins Bird Guide to enjoy one of the highlights of that first afternoon: a huge flock of glossy ibis in flight, its undulating lines like the streamers of some giant kite.

Earlier, we had passed several flocks of glossy ibis on the ground, Elizabeth counting 92 of the birds in one place. On the way back to the hotel, Julian told us that people regularly underestimate in such counts by up to 15 per cent, so bird and wildlife surveyors add 15 per cent to compensate. It was a remark that would become a running gag for the rest of the trip.

That evening set the pattern for the week. We returned at dusk to our hotel, a rustic single-storey place of pine and white walls. We had a drink in the bar, moved into the restaurant for dinner, then reclaimed our original seats to hear a reminder from Julian of where we had been and to list what we had seen. The others did the ticking-off; I was happy to listen in.

Day two took us back to the Canal Vell, its reeds golden in the morning sun, then to a windswept beach with an end-of-season feel at Riumar, then right across the northern delta to the coastal town of L’Ampolla and the reserve of Bassa de les Olles. Along the way we passed signs saying “Reserva de Casa” (hunting), a reminder that many visitors to the delta are intent not just on watching wildfowl but on shooting them.

Some species we had now seen so often we barely bothered to mention them, including the great white egret. Yet only seven years earlier, Julian told us, it had been a scarce bird here. Numbers were increasing, too, of wintering osprey, but we still felt privileged to see one in pursuit of a fish — not so much knifing into the water as blasting.

In the bar that night, once bird species had been accounted for, Julian asked about other wildlife. Liz had seen a lizard: “It was when I was behind a bush.” Deirdre: “That’s what you call multi-tasking.”

On day three we were heading inland by 8.30, the low sun lighting every blade of stubble. The fields were still as glass, the water moving only under the feet of the birds. We passed a sign for a theme park. “Dinosaur!” Elizabeth shouted, and Mike responded: “That’s definitely a write-in.”

“Pseudo-steppe” was how Julian had described our destination, and — but for the view of the city of Lérida on one side — we might have been in Central Asia: a rolling brown land with a few pyramid-like hills, so dusty that the ploughmen in the stony fields had handkerchiefs round mouth and nose. Dusty, but far from barren.

Elizabeth alerted us to a hare, streaking between two rows of bushes. Crested lark and skylark picked their way among the furrows. Some way off, Mike spotted a little owl, and Julian trained his telescope on it so we could each have a closer look at its broad head, speckled breast and yellow eyes. Jane spotted a merlin, which took fright and flight when Mike opened the minibus door. Circling above us was a flock of linnets.

After dinner that evening, Elizabeth said she reckoned she had by now seen 91 species of birds.

“How far have you driven?” Jane asked Julian.

“Two hundred and fifty kilometres,” he guessed.

“Plus 15 per cent,” said Mike.

In the morning, with the forecast promising high winds and showers, we drove to the southern half of the delta, pausing at a hide to see a couple of trees draped with egrets as if with Christmas lights. We were heading for Punta de la Banya, a 6,000-acre reserve of beach, dunes, salt marsh and salt mine — the product of the last heaped in a shimmering white pile ahead of us.

The journey proved to be the highlight. To reach the reserve, we drove along a spit of land with water on both sides. Towards the end, there was more water than sand, and Julian, fearful that the minibus would get bogged down, suggested that the rest of us get out and walk while he eased it through the wettest stretch.

Once parked, we had another walk of a mile and a quarter, the tide making pools not only on the seaward side but sometimes behind us. After that, the birding was a bit of a letdown, with little to be seen through mist and drizzle.

Our next stops, the Tancada Lagoon and Riet Vell, proved more rewarding. At the latter, a reserve surrounded by organic rice fields and owned by the SEO (Sociedad Española de Ornitología), we finally caught sight of a species that had been playing hide-and-seek with us for days: the bluethroat, a small, long-legged member of the chat family that is renowned for mimicking other birds (and even reindeer bells). Julian heard one call, spotted it in the open, and then turned his telescope on it so we could each admire its bright blue bib.

Of Europe’s 20,000-or-so pairs of griffon vultures, 90 per cent are reckoned to be in Spain. One of the best places to see them is the Els Ports natural reserve, in the mountain chain known as the Sistema Ibérico, where we spent our last full day. We were still on the outskirts when Julian caught sight of a couple, and we tumbled from the minibus to watch them circle overhead, on broad wings that ended in long “fingers”.

We had only just entered the park proper, chasms opening up on one side, peaks soaring on the other, when a blur of horns and hooves crossed the road and got under cover. “Iberian ibex,” Julian said — the wild goat of the mountains.

A couple of hundred yards farther along, a red squirrel — darker than any reds I have seen elsewhere — darted down a tree and across the road. We stopped, eased open the doors, and caught sight of it disappearing up another tree. For the next quarter of an hour, until rain drove us into shelter, I struggled to see anything much in the canopy, as the others ticked off mistle thrush, serin, nuthatch, and crested, coal and blue tit.

Then, following a pause so we could eat our packed lunch, it was my turn. Alerted by Mike to the sound of drumming, I wandered 50 yards or so away from the group, and spent three or four minutes with my binoculars trained on the black-and-white plumage of a great spotted woodpecker. When it flew off, I strolled back down to the others — and realised that they were still trying to locate it.

None of us missed the next appearance of the ibex. First a female and her calf wandered down a distant ridge; then another female stepped right to the line where ridge met sky, as if to give us an uncluttered view through the telescope.

At a mirador (viewpoint) where we stopped on our return journey, a griffon vulture was equally obliging, pausing on a rocky platform so we could have a good look through the telescope at its brown body, white ruff and yellowish bill. I’ve seen those features caricatured often, but this wasn’t a bird in a cartoon, this was a bird in command.

Back near sea level in our hotel that night, one offering on the menu was “Arrossejat del Delta”. Delta rice with something — but what? “Nothing,” said our waiter with a smile. “It’s rice with rice, but it’s very good.” And so it was: like a fish paella from which the flesh of the fish had been removed.

Then came the final post-prandial tallying of bird species. In all, Julian reckoned, we had seen 123 in five days. My own count was considerably lower, but my senses had definitely been heightened. Back home next morning, on my walk to the newsagent’s, I saw birds everywhere.

** In April this year (2025), the BBC reported that ring-necked parakeets had been spotted for the first time in Northern Ireland, in the Waterworks Park in Belfast.

Leave a Reply