Less invasive species than cinematic extras: palm trees brought to the Spanish desert of Tabernas from Alicante, 150 miles away, for the filming of a scene in the 1960s in David Lean’s ‘Lawrence of Arabia’. Picture: NICK HUNT

July 26, 2022

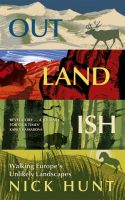

In his acclaimed book ‘Outlandish’, newly published in paperback, NICK HUNT walks through European landscapes that seem like places from elsewhere: Arctic tundra in Scotland, primeval forest in Poland and Belarus, a desert in Spain and grassland steppe in Hungary. His journeys, he says, not only led him backward, into pre-human history, glacial landscapes and great migrations, but also forward, ‘into a future whose map we are only just starting to glimpse’

The place that is sometimes called “England’s only desert” can be reached by a miniature railway line that runs to a nuclear power station on one of the largest expanses of shingle beach in Europe. Across the pebbled coastal plain a tiny, gleaming steam engine chugs bravely and ridiculously past weather-beaten huts and abandoned fishing boats, to deposit its passengers near the foot of a black lighthouse. The power station hums inland, too brutally large to understand. Ahead, the shingle foreshore lilts towards the sea. Sections of board-walk lead visitors out across the stones, past rusted bits of winching gear and outcrops of sea kale; in summer, the pebblescape is red with poppies. As you step off the wooden boards, stones crunch with every step. The shingle is composed of flint. If you bring your boots down hard, your footsteps might strike sparks.

The English desert of Dungeness draws a million people a year, pilgrims to its weirdness. Why go to the Sahara when you can visit Kent? The headland noses out from the south-east coast towards Boulogne-sur-Mer, 30 miles across the sea. It is out on a limb, on its way to nowhere.

We did not arrive by train, my partner Caroline and I, but by cycling eastwards along the sand-duned coast from Rye, inland through the town of Lydd, and then back towards the sea. Despite the cloudless, glaring sky, what felt like a gale-force wind tore against us all the way, dragging the breath from our lungs if we faced directly into it, so that we progressed like drunks, teetering and gasping. At times the wind almost forced us to retreat, or into the shelter of barriers raised against the sea, but soon there was no shelter left. Ahead lay only pebbles. The emptiness seemed immense and we became extremely small. Distances were hard to gauge, proportions misaligned.

We stayed for a week in Dungeness in one of the iconic huts – it belonged to the family of a friend – and spent our days walking the foreshore and our evenings watching the sun collapse in a wobbling orange ball, like a shot-down UFO. The sky was not the English sky but the sky of a greater continent, with a clearer quality of light. Our discoveries got stranger. Astonishingly for what looks, at first glance, like a desolate place, this headland provides a habitat for a third of Britain’s plant species, many of them rare; the ceaseless sifting of the sea sorts the pebbles into troughs and ridges that trap rainwater, creating small pockets of life. Sculptures of drift-wood and scrap metal protrude along the shore, the creations of artists drawn here by the legacy of Derek Jarman, the avant-garde film director who coaxed a garden from the stones. And in one strange spot offshore, hidden pipes discharge hot water from the nuclear power station (actually two nuclear power stations, Dungeness A and Dungeness B) into patches dubbed “the boils”, where the warmer temperature attracts tiny sea creatures which, in turn, attract shoals of fish and wheeling seagulls. The waste water is – apparently – clean, but it is hard to overcome suspicions of mutant energies. A common description of this coast is “post-apocalyptic”.

One evening at sunset, with crimson light pouring over a scene of wind-whipped marram grass and the skeletons of boats, I experienced a moment of dislocation; suddenly I was not in England but in a North American wasteland, some time in an imagined future that felt dreamily familiar, surrounded by the flotsam and jetsam of a collapsed culture. The light; the rusted metal cables; the plants like deformed cabbages; the presence of the power stations with their mysterious blinking lights; the landscape’s sheer outlandishness: it was briefly enough to jolt me free from time and place. “Outlandish” comes from the Old English ūtland, which means “foreign country”, and that was this desert’s uncanny effect. It made my country foreign.

Dungeness – disappointingly – is not actually a desert. In less taxonomic times the word was more cultural than geographical, meaning simply a place that was deserted (from the Latin desertum) but scientific classification has now fixed the term in place and there are climatological parameters that this headland does not fit. To qualify as a true desert an area must receive less than 250 millimetres of precipitation a year. Dungeness gets more than that – the sea kale, sea holly, orchids, vetch, broom, sorrel, sage, bugloss, poppies and 600 other species of plant are proof – too much rain falls even here, in one of Britain’s driest places. In 2015 the Met Office, in response to a newspaper claim, officially refuted the myth of the shingle’s desert status.

Nevertheless, for a moment there, I found myself transported.

My book is about places like that. Places that transport. Portals.

After our week in Dungeness, the experience stayed with me. It had been like falling into the clear light of another world, a place that was “altogether elsewhere”, like the line in that Auden poem that had always tugged at me. But it was not elsewhere, not far away at all. What was it about the thought of a desert – even a not-really-desert – nestled in the south-east corner of England that was so exhilarating? England should not possess a desert, or anything remotely resembling one; the very hint of such a thing felt dangerous and subversive. Deserts surely belong in places that are remote and far away from this green and pleasant land, or from this over-civilised time. There should be no place for them here. And yet here one (almost) is.

Following on from that Kentish desert was a West Country rainforest; another place that tipped me unexpectedly into elsewhere. On a cold February day I went in search of Wistman’s Wood, a sliver of ancient oak woodland on Dartmoor, and discovered a dwarf jungle of contorted green limbs clustered with mosses, lichens, ferns and other epiphytes – plants that grow on other plants, a common indicator of rainforests – which felt like stepping into a primordial other-world. Patches of temperate rainforest can also be found in riverine valleys in the north-west of Wales, on the Atlantic coasts of Scotland and Ireland, and in Cornwall and Cumbria (sometimes they are romantically called “Celtic rainforests”), part of a coastal temperate rainforest biome that reaches east to Japan and west to the Pacific seaboard of North America. As with deserts, rainforests seem to belong to somewhere far away, but their existence should hardly be surprising in a place where it rains all the time. “Learning that Britain is a rainforest nation astounds us only because we have so little left,” writes the journalist George Monbiot; once, the dripping canopy covered most of these islands.

Casting around for the feeling these moments most reminded me of – the Dungeness desert and the Devon jungle – what came to my mind was snow, the meagrest sprinkling of which has the ability to transform the everyday into the extraordinary: a lawn into a frosted steppe, a suburban park into a taiga.

At the beginning of 2019 I yearned for more of that feeling.

The year before, devastating fires had swept across the world, burning millions of square miles in places where they hadn’t burned before, or never on such a scale, from the Mediterranean to the Arctic Circle. (I couldn’t have imagined it then, but the Amazon was to go up in flames a year later.) In the Arctic and the Antarctic, as well as across the world’s mountain ranges, glaciers and ice caps were melting at an unprecedented rate. Climate breakdown – which, until then, had felt like a distant future emergency, alarming in an intellectual but not a tangible way – was suddenly made real to me in a way it hadn’t been before. The perfect archetypal landscapes I had believed in as a child – the mountains capped with snow and ice; the dense dark forests stretching away, impenetrable and vast; the endless plains of yellow grass and golden moss seething in the wind – were not immutable features of the world, somehow immune from change. Glaciers were melting into slush and rainforests desiccating into savanna; from continent to continent, distances were becoming less vast and empty horizons were being filled in with the clutter of the Anthropocene. As I stumbled upon these English outlands, the greater outlands of the world were vanishing or being changed beyond all recognition.

As a travel writer increasingly aware of the damage that travel can do – mainly, of course, the chemical violence done to the stratosphere by flying – I was looking for transformative journeys that lay closer to home. My previous books had been about walking and Europe, and in both of them I had experienced states of outlandishness. Often those states had not occurred in remote wildernesses but in close proximity to towns, roads and agriculture, and this proximity somehow increased, rather than diminished, their magic. It seemed a version of the Celtic conception of the otherworld, which exists alongside our own, and can be accessed in certain locations, or in certain frames of mind. As the Welsh mystic Arthur Machen wrote of early 20th-century London: “He who cannot find wonder, mystery, awe, the sense of a new world and an undiscovered realm in the places by the Gray’s Inn Road will never find those secrets elsewhere, not in the heart of Africa, not in the fabled hidden cities of Tibet.”

While I wanted to venture a little further abroad than the Gray’s Inn Road, the idea that wonder, mystery, awe, new worlds and undiscovered realms might lie a train ride away, rather than on a carbon-intensive flight to the far side of the globe, opened up possibilities for a different type of travel. What other unlikely landscapes might be lurking out there, ready to snatch the unwary traveller into the outlandish?

Europe is sometimes referred to as the world’s only desert-free continent (there are frozen deserts at the Poles) but a bit of research revealed examples of other desert-like places where you would least expect to find them. In the south of Romania – in my mind so richly green – desertification catalysed by communist-era deforestation has created an area popularly known as the Oltenian Sahara, which grows larger every year. Serbia has its Deliblatska, a region of sandy hills that once formed the bed of a sea; before tree-planting programmes in the 19th century, sand was reported being blown as far west as Vienna. And in the heart of Poland lies the anomaly of Błędów, another semi-desert that owes its existence to human greed. Centuries of deforestation caused the topsoil to erode and exposed a bed of ancient sand (though local legend blames the devil, who dumped the sand in order to bury a nearby silver mine). During the Second World War, Germany’s Afrika Korps trained there. Poland became a practice ground for deployment in the Sahara.

Again, none of these are deserts in the strict scientific sense – mainland Europe has only one true desert, which I explore in this book – but learning of the existence of these geological oddities expanded the imaginative horizons of the continent; suddenly it felt larger, somehow older and infinitely more unknown. Following this outlandish thread, I discovered that there are fjords in Ireland (three of them, all in the west); bizarrely eroded “badlands” in the south of France and Italy, respectively known as calanques and calanchi; and western Europe’s only steppe is stranded in Provence. The thing that drew together such wildly different topographies was the fact that each of them seemed to belong to another part of the world, or even to another historical or geological era. Fjords should be Scandinavian (or, at a pinch, Chilean); badlands are associated with the North American frontier; steppes are properly situated in the grassland tracts of Mongolia, Central Asia and southern Russia. All of them are exclaves, which is normally a geopolitical term describing a region that belongs to another country but is not connected to it by land, and finds itself alone, surrounded by alien territory.

At Ősök Napja, a festival celebrating steppe culture at Bugac, in western Hungary. The man in the wide-brimmed hat is dressed as a csikó, a Hungarian cowboy; the others are wearing regional folk costumes. Picture: NICK HUNT

I began to think of Europe’s outlands – these portals to elsewhere – as exclaves not only of place, but of deep time. Of all the outlandish places I learned about, four in particular called to me, and became the four chapters of this book: a patch of arctic tundra in Scotland; the continent’s largest surviving remnant of primeval forest in Poland and Belarus; Europe’s only true desert in Spain; the grassland steppes of Hungary. As well as their surface connotations of geology and ecology, all of them had deep, and often surprising, cultural links with faraway regions of the world – the Arctic, the Siberian tundra, the badlands of North America, the Sahara, the steppes of Central Asia – and the act of stepping into them, and the alchemy of walking, were a means of being transported without setting foot outside this small, supposedly tame continent (which, especially to a walker, is neither small nor tame). These journeys through snowstorms and burning sun, mountains and deserts, forests and plains, were also walks through time. They did not only lead me backward into pre-human history, glacial landscapes and great migrations – by way of Paleolithic cave art, reindeer nomads, desert wanderers, shamans, Slavic forest gods, ibex, European bison, Wild West fantasists, eco-activists, horseback archers, Big Grey Men and other unlikely spirits of place – but forward, into a future whose map we are only just starting to glimpse.

Perhaps the result is not a nature book, or even a travel book, so much as a book of fantasy: four small pilgrimages into the imagination.

In fading light we walked to where the stony plain met the waves, past hunched fishermen and the cannibalised wrecks of boats. The lighthouse beam probed the sky with the power of a hundred thousand candles. As night came on, the almost-desert merged with the greying sea.

We found ourselves in an open space that expanded on and on, populated by the blinking lights of trawlers floating off the coast and the right-angled monoliths of Dungeness A and Dungeness B shimmering inland. Beneath our boots the shingle shifted like a bed of atoms. Thousands of years stretched between the flints whose striking once sparked fire and the nuclear power station whose waste will last for centuries more, a monument both to eternity and to extreme fragility. For a moment in the dark we stood between the past and the future; between what lay beneath our feet and what looms on the horizon.

Extracted from Outlandish, published in paperback by John Murray at £10.99.

© Nick Hunt, 2017.

Nick Hunt is the author of two other travel books – Where the Wild Winds Are and Walking the Woods and the Water – as well as a work of “gonzo ornithology”, The Parakeeting of London. His debut collection of short fiction, Loss Soup and Other Stories, was published in May. He is an editor and co-director of the Dark Mountain Project, and an editorial consultant for John Murray Press.