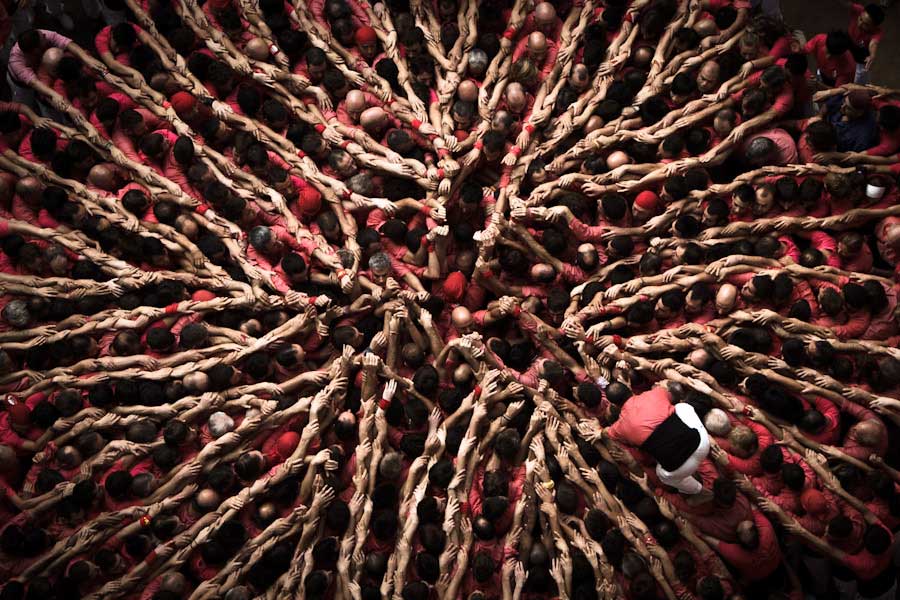

The castell, or human tower, which Christopher Howse describes towards the end of the piece below, is something of a specialism of the photographer David Oliete. The image shown here is of a competition among teams of castellers in his native Tarragona in 2012. Another he made at the same competition was highly commended in the “One Shot” category of the 2013 Travel Photographer of the Year competition.

Picture © David Oliete 2014. For more of the photographer’s work, see his website.

‘The Train in Spain’ by CHRISTOPHER HOWSE is not, he says, about trains, but about the variety of Spain. This extract from his 3,000-mile circumnavigation of the peninsula by rail takes him from Tortosa to Tarragona on the Mediterranean

A man stood at the counter of the cafetería at Tortosa station. He was drunk. He had difficulty with his words and his limbs moved in unplanned directions.

Public drunkenness is taboo in Spain: it is not so much forbidden as despised. “Rare to see a Spaniard drunk,” Samuel Pepys noted in 1683. “So that it is enough to take away the credit of a public notary to be proved to have been seen in a tavern.” A century or so later, the same trait was just as noticeable. “Temperance is, and ever has been, a distinguishing characteristic of the Spaniard,” wrote Alexander Slidell Mackenzie in 1829. A friend and fellow-countryman of Washington Irving, Slidell published A Year in Spain when he was 26, under the pen-name A Young American. It was a bestseller in Britain for Byron’s publisher, John Murray.

When he came to sum up the Spanish character, sobriety struck Slidell forcefully. “Aversion to drunkenness amounts to destestation,” he wrote. “Mention is said to be found in Strabo of a Spaniard who threw himself into the fire because someone had called him a drunkard.”

There is drunkenness and drunkenness. It is a question of comportment, of how one behaves when drunk. At a fiesta in a village or in a city, when everyone is together and it is getting late, then people will be drunk. Even so, there is no feeling of being threatened. Parents will go about with little children.

But young people have in the past 20 years acquired the British convention of getting drunk with large amounts of beer, late at night. Drugs are also used to a varying degree. Informal meeting-places in the street can attract large numbers. The word that describes this use of drink is botellón, “a big bottle”. Prohibido “El Botellón” say street signs, invoking recently passed laws by name and date.

Anyone who is familiar with formerly quiet back streets, even in genteel places such as El Escorial or Pontevedra, can see the change over a generation. Sometimes local people complain. In 2006 a square near the cathedral in Guadix was hung with sheets painted with slogans in big black letters: BASTA BOTELLON. ESCANDALO – ALCOHOL, DROGAS, “MIAOS”, VOMITAS.

By miaos, the protest banner was referring not to the drug mephedrone (sometimes nicknamed miaow-miaow in English) but to home-made mixtures of spirits and fruit juice that youngsters bring to the nocturnal gathering. A banner opposite declared: QUEREMOS DORMIR – We want to sleep.

But the drunk man in the station bar belonged to another convention. He was in his fifties, a manual worker, alone, it was Sunday afternoon and he had enough money for a drink. Perhaps he had a wife at home. There would be plenty of other men at home asleep. To be drunk in public is to court shame, vergüenza, and vergüenza only works where you are known. In a big city, people can behave sin vergüenza, or shamelessly.

Another style of being drunk is followed by men who have some money, dress in a suit, with a clean shirt, perhaps with a golden bracelet on one wrist, smoke cigars, are overweight and have rasping voices from drink, smoke and late nights. They are approved of by their circle of male friends and often argue loudly in a joshing fashion, but are not obviously out of control. They restart the day with brandy.

AN HOUR DOWN the line at Tarragona, a lion jumped down the steps and the children screamed. These steep, wide steps ran up to the cathedral, and the lion wore a crown, for it was the feast of St Thecla – Santa Tecla – which was to last for ten days, with loud drumming, trumpets, drink, crowds, close-up fireworks and more drink, day and night.

The adopted drink of the fiesta was, surprisingly, Chartreuse, green or yellow, in bottles with special Santa Tecla labels. The emblematic T of Santa Tecla, shaped like a Franciscan Tau-Cross, was everywhere in Tarragona. The Chartreuse was drunk as a granizado, with pulverised ice, from litre flasks. In another context this would be a botellón or “doing the litre” as another modern phrase puts it. But as part of the fiesta it was not a story of bored, inebriated youth in opposition to settled customs of behaviour. Everybody was joining in.

On these 19 high steps of Roman masonry (from the ancient Forum), linking the Carrer Major and the little cathedral square, children sat on their fathers’ shoulders, or in their mothers’ arms, joggling in time to the beat of the drum and the fierce-eyed lion. “Papa!” called out a woman, not to her father, but to the father of her children, who was manoeuvring the pushchair.

Later came the Drac, the dragon breathing fire and covered with spikes, on which fireworks rotated and exploded. There was another beast too, 10 feet high, called a Vibria, winged, beaked and clawed, with a woman’s breasts. The one that was carried here weighs 180 pounds, but danced as lightly as the lion. A toddler standing on the lid of a wheelie bin jumped up and down with over-excitement, wafting out rubbish-flavoured billows, as the simple dance tune was repeated again at greater volume. It was all so happy that it seemed nothing else mattered. The crisis (the economic crisis) was submerged by the fiesta.

A conga of T-shirted young people appeared in front of the cathedral, preceded by the stupendously loud beating of a drum, sending the pigeons up in a wheel of wings. This cathedral square is beautiful by accident. It fronts the façade of the cathedral, where martins glue their nests of mud to the triple Gothic door-arches. On one side, the old houses rest on ground-floor pillars. On the other, the walls of the houses are variegated with hundreds of years’ patching and rendering of stonework, with one beautiful window divided by characteristically thin Catalan columns headed by trefoil tracery. The stone platform of the square is supported by gigantic, ancient Roman blocks, with a street of pointed arches running to one side.

On this dramatic stage, the day before, as at other points throughout the city, the castellers had performed. These clubs of young people build human castles, towers, six, seven, eight storeys high. At the bottom they are crushed together by human props squashing them, in order to resist the outward pressure. The numbers in each storey diminish until, at the top, one small child stands alone. Often the towers fall down on to the delighted crowd.

Not only are the castles built in the crowded squares, but they walk. A local policeman on a motor bike makes way for them as they sway through the street. It is madness – or perhaps co-operation, courage, skill and grace.

Extracted from The Train in Spain: Ten Great Journeys through the Interior by Christopher Howse (Bloomsbury).

Extracted from The Train in Spain: Ten Great Journeys through the Interior by Christopher Howse (Bloomsbury).

Christopher Howse is a journalist and the author of A Pilgrim in Spain (2011).

Leave a Reply