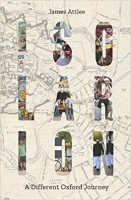

How far do you have to go to write a travel book? With trains, boats and planes currently being seen less as vehicles of adventure than vectors of infection, it’s a topical question. And it’s one that JAMES ATTLEE addresses directly in his book ‘Isolarion’, which has just been republished. His answer: to a street in your own neighbourhood. Here, in the introduction, he explains why he didn’t have to go any farther

How far do you have to go to write a travel book? With trains, boats and planes currently being seen less as vehicles of adventure than vectors of infection, it’s a topical question. And it’s one that JAMES ATTLEE addresses directly in his book ‘Isolarion’, which has just been republished. His answer: to a street in your own neighbourhood. Here, in the introduction, he explains why he didn’t have to go any farther

A time may come in your life when you feel the need to make a pilgrimage. A time when the pressure to return your staff pass, kiss your loved ones goodbye and set out on a journey becomes too insistent to ignore.

The impulse that propels you may be religious or it may be secular. Perhaps the words of a preacher have ignited a fire in your heart; or perhaps the dusty volume you stumbled across on the shelves of a second-hand bookshop has awoken a thirst for distant shores that cannot be shaken. You may be sick at heart or in body, in need of counsel or immersion in healing waters. The passage of a birthday may have triggered the desire to seek out the birthplace of your ancestors or revisit a scene from your childhood.

The motivations of pilgrims are as varied as their destinations. You may be headed for a holy city, a site of revelation or miracles, where a god has appeared or a prophet has spoken. You may wish to visit the place where a composer brooded, a poet walked or the graveyard where a singing voice lies buried. There may be a rite you must perform or a memory you need to lay to rest.

Jerusalem, Mecca, Rome, Graceland, Thebes, Varanasi, Bethlehem, Tepeyac, Père-Lachaise.

And so you consult an astrologer or a travel agent, close up your house, give instructions to your servants, smear your forehead with ashes, slit the throat of a quiescent herbivore, smash a coconut on the pavement, take up the flagellant’s whip, board a train, a tourist coach, an aeroplane or a leaking tramp steamer, or simply put on or take off your shoes and walk, run, shuffle, dance or crawl on your knees up holy mountains, rocky paths, marble steps and glaciers, braving war zones, border guards, conmen, rapacious hoteliers, foreign food and (most of all) your fellow travellers.

Perhaps you wish to know your God better. Perhaps it is yourself you wish to get to know. Whatever your intention, one thing is certain: that the end of the journey will not be as you imagined.

Medina, Lumbini, Gangotri, Bodhgaya, Santiago de Compostela, Shikoku, Valldemossa.

Certain, too, is that your singing, stamping, shouting, chanting, weeping, whirling and prostrating; your basilicas, temples, grand hotels and coach parks; your tented cities and smoky campfires on the banks of great rivers all look much the same from space. Which is not to denigrate any of the traditions that set these journeys in motion and give them structure, for they are clearly one of the things that mark us as human.

For we do not all migrate as the eel or the caribou, the swallow, the tern or the salmon. We are equally driven, but our goals are less explicable, our needs more arcane. The journeys we undertake do not necessarily involve travelling large distances. Many of us are not free to set aside our responsibilities for an extended period; there are mouths to feed, bills to pay, deadlines to meet that keep us entangled in the present, anchored to our locations and yet jerked here and there by the breeze from another place, like thistledown caught in a web.

This was my situation. Yet gradually it dawned on me that the voyage I needed to make began in my own neighbourhood, within a few minutes’ walk of my front door. It had been there all the time, under my nose, even as I made other abortive attempts to discover a starting point. This would be an urban, postmodern, fragmentary pilgrimage that could be dipped in and out of, freeze-framed and rerun, visited between other commitments — and yet nonetheless a voyage of discovery for all that.

There is an old road in my neighbourhood that follows approximately the path that ran between the city walls of Oxford and the medieval leper hospital at Bartlemas, and beyond it to the village of Cowley. Until the beginning of the nineteenth century, farmers still grazed their flocks and made hay in the unenclosed meadows and marshland that lay outside the city wall. Cowley Road is now the main thoroughfare through East Oxford, connecting the academic and touristic heart of the city with the Cowley Works, the car factory that in its heyday in the 1960s employed over twenty thousand people and has been a magnet for immigrant workers since the 1920s.

Its name is derived from the Anglo-Saxon, a combination of the word lea, a glade or clearing in the forest, and the name Cofa — Cofa’s Glade. Today it is lined with businesses that seem to represent every nation on earth. Among them are Jamaican, Bangladeshi, Indian, Polish, Kurdish, Chinese, French, Italian, Thai, Japanese and African restaurants; sari shops, cafés, fast-food outlets, electronics stores, a florist, a Ghanaian fishmonger, pubs, bars, three live-music venues, tattoo parlours, betting shops, a Russian supermarket, a community centre, a publisher, the headquarters of an international NGO, musical-instrument vendors, butchers (halal and otherwise), three cycle shops, two video rental stores, post offices, two mosques, three churches, a Chinese supermarket, a pawn shop, a police station, two record shops, two centres of alternative medicine, a late-night Tesco, an independent cinema, call centres, three sex shops, numerous grocers, letting agencies, a bingo hall and a lap-dancing establishment that plies its trade on Sundays.

Why make a journey to the other side of the world when the world has come to you?

****

Have they not travelled within the land so that they should have hearts

with which to understand, or ears with which to hear? QUR’AN 22.46

I live in a famous city, a city that has been sold to you in a thousand ways. A myriad of writers have set their dramas upon its ancient streets, discoursed upon its architecture and provided guides to its quads and colleges. Few even mention the Cowley Road, let alone the people who live and work there. Many of its inhabitants have made their own journeys from far away, under all kinds of circumstances. They have brought with them not only their cuisine, but also their beliefs, their values, their trades, their prejudices, the stories of their past and their hopes for the future. This is the other Oxford, the one never written about. This city has dispatched anthropologists, explorers, scientists, authors and poets to every nation represented on Cowley Road. Perhaps it is time to flip the coin and see ourselves through their eyes.

In 1994 the artist Francis Alys walked through the streets of Havana wearing a pair of specially constructed magnetic shoes. Three years previously he had taken a magnetised metal “dog”, that he christened The Collector, for a walk through the streets of Mexico City. At the end of these “strolls”, both the shoes and The Collector were covered in the metal detritus of the city. Somehow this accretion was redolent of the overheard conversations, snatches of music, smells, and other sensory impressions that one gathers on an urban walk.

I have no magnetic shoes. Instead I carry a notebook, a pen and an old-fashioned cassette recorder loaded with magnetised tape, with which I intend to capture the sounds of the voices I encounter. One way in which to classify people is by which sense they primarily relate to the world. We can all think of friends who consume life; who, when they are not cooking or eating, are constantly picking at, shopping for or reading about food. Others are dominated by the visual, sensitive to the coded messages of colour and design embedded in their habitat by nature and human ingenuity. Then there are the tactile ones, constantly reaching out to touch and stroke, sensitive to the fabric and texture of life.

For yet another category, it is the sound of things that matters. As a child I progressed through the world testing the resonance of surfaces made of wood, plastic, metal, stone. I was constantly being told to stop tapping my feet, drumming my fingers, beating out a rhythm on whatever came to hand. Even today, in the middle of laying a table, I can become distracted by the ability of the “give” in the blade of a knife to approximate the spring of a snare drum. Now it is my wife and children who beg me to desist, and I am genuinely surprised: Can’t they hear how great that sounds? Given this predilection, it is only natural that I am interested in capturing the aural landscape of the road as well as its visual qualities and wafting odours. My analogue tape recorder will replace Alys’s magnetic shoes. At those times when a recording device is inappropriate — in casual conversation, interacting with friends and neighbours — I will have to press a button in my head marked Record. Then, when I summon up the characters that I have met upon my journey in the eye of my imagination, I will run the conversation again and try to convey their words as exactly as I can.

It was Heraclitus, of course, who came up with the formulation that we are never able to step into the same river twice. If the Cowley Road is a river, the big fish lie hidden beneath the surface in the shadow of its banks: landlords, entrepreneurs, developers, local politicians, wheeler-dealers, import-export men.

The obverse of Heraclitus’s maxim may be that one is never able to step out of the river the same, twice. A neuron in the brain is altered with every experience. The self, if it exists, must be a constantly evolving thing. Those coming to the banks of the Ganges or the Jordan to immerse themselves do not expect to leave the same as they arrive. Perhaps this will apply to me, too.

Because we are at war*, I learn that Muslims are buried on their right shoulder, facing Mecca. I am astounded that I never knew this simple yet fundamental detail. People are living and dying all around me, the formative rituals of their lives as hidden as the rites of a people half a world away. Perhaps this is always so. In any case, it cannot hurt to attempt to lift a corner of the curtain.

I wind up my radio before hanging it on the corner of a radiator and stepping into the shower. In The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, Haruki Murakami uses the song of the wind-up bird as a motif for the engine that keeps life going. For me it is the sound that the handle of my wind-up radio makes that starts the day.

Two academics are having a discussion about transport problems as I apply the soap. “A hyper-mobile society is an anonymous society,” one says. For seven years I have been getting up at an unholy hour to travel by train back to London, where I have lived for most of my adult life, to work. In many ways I still feel more rooted there than in Oxford. I was used to inhabiting a city abundant in space and spectacle, large enough to lose myself in. A hyper-mobile man, I have to learn to travel more thoughtfully, to slip beneath the surface and explore more deeply.

Space is relative. One aim of my pilgrimage will be to connect me to the neighbourhood in which I live. At the same time, perhaps my journey will offer clues to a wider reality. Oxford is an untypical city, its centre preserved in aspic for the tourists, its biggest landlord an ancient institution that still owns an inordinate amount of its buildings. Much of the change and diversity in the city has therefore been concentrated into a small area, its visible expression squeezed like toothpaste from a tube along the length of Cowley Road. Paradoxically it is this place, often overlooked or omitted from the guidebooks, that is a barometer of the health of the nation. It is both unique and nothing special. It could be any number of streets in your town. For that reason alone, it seems as good a place as any from which to start a journey.

* Britain, having joined an invasion of Iraq by US-led coalition forces in 2003, still had troops there in 2009, when the first UK edition of Isolarion appeared.

Extracted from Isolarion: A Different Oxford Journey (And Other Stories)

© James Attlee 2007

Freya Warsi, an actor who grew up near the Cowley Road, has started a new books podcast, “Water Boatwoman”. Its first season, on psychogeography, begins with Isolarion.

James Attlee is the author of Guernica: Painting the End of the World; Station to Station, short-listed for the Stanford Dolman Travel Book of the Year 2017; and Nocturne: A Journey in Search of Moonlight, among other titles. His digital fiction The Cartographer’s Confession won the New Media Writing Prize in 2018.