A couple of books published this month that I’ve not had a chance to mention before: Tender Maps by Alice Maddicott and A River Runs Through Me by Andrew Douglas-Home.

Maddicott, a writer and artist, had taken weekly walks for years in a forest near her home in Somerset. During the coronavirus pandemic, she felt as though she were experiencing the place in an entirely different way; that she was more alive to atmosphere than she had been since she was a child. In Tender Maps (September Books, £19.99), she explores the “personality of place” through her own travels and those of others, and examines how writers and artists have responded to it. The result, her publisher says, is “a beautifully evocative book of travel, culture and imagination that transports readers in time and place”.

Maddicott, a writer and artist, had taken weekly walks for years in a forest near her home in Somerset. During the coronavirus pandemic, she felt as though she were experiencing the place in an entirely different way; that she was more alive to atmosphere than she had been since she was a child. In Tender Maps (September Books, £19.99), she explores the “personality of place” through her own travels and those of others, and examines how writers and artists have responded to it. The result, her publisher says, is “a beautifully evocative book of travel, culture and imagination that transports readers in time and place”.

Douglas-Home has lived on the banks of the River Tweed for most of his life. He was awarded the OBE in 2019 for his services to fishing and Scottish culture, recognising his work in helping to secure the environment of the Tweed and the legacy of Sir Walter Scott and the riverside house he built, Abbotsford. In A River Runs Through Me (Elliott & Thompson, £16.99), he offers an “evocative account of one man’s life spent fishing on arguably the world’s best salmon river: a story of family, tradition and the Scottish countryside”.

Douglas-Home has lived on the banks of the River Tweed for most of his life. He was awarded the OBE in 2019 for his services to fishing and Scottish culture, recognising his work in helping to secure the environment of the Tweed and the legacy of Sir Walter Scott and the riverside house he built, Abbotsford. In A River Runs Through Me (Elliott & Thompson, £16.99), he offers an “evocative account of one man’s life spent fishing on arguably the world’s best salmon river: a story of family, tradition and the Scottish countryside”.

Quite a few writers in recent years have sought to bring home to us the likely effects of climate change by showing what it will mean for one particular place, from Earl Swift, in Chesapeake Requiem, on Tangier Island, to Tom Bullough, in Sarn Helen, on Wales. In Charleston: Race, Water and the Coming Storm (Indigo, August 24, £13.99), Susan Crawford, a Harford Law School professor, offers a portrait of a city that was founded by English settlers in 1669 as a hub of the sugar and slave trades, and which now, as the waters rise, “stands at the intersection of climate and race”. Her account, weaving together science, narrative history and the family stories of Black Charlestonians, “chronicles the tumultuous recent past in the life of the city – from protests to hurricanes – while illuminating the escalating riskiness of its future”.

Quite a few writers in recent years have sought to bring home to us the likely effects of climate change by showing what it will mean for one particular place, from Earl Swift, in Chesapeake Requiem, on Tangier Island, to Tom Bullough, in Sarn Helen, on Wales. In Charleston: Race, Water and the Coming Storm (Indigo, August 24, £13.99), Susan Crawford, a Harford Law School professor, offers a portrait of a city that was founded by English settlers in 1669 as a hub of the sugar and slave trades, and which now, as the waters rise, “stands at the intersection of climate and race”. Her account, weaving together science, narrative history and the family stories of Black Charlestonians, “chronicles the tumultuous recent past in the life of the city – from protests to hurricanes – while illuminating the escalating riskiness of its future”.

As a schoolboy, Nick Acheson says, he found his flock among birdwatchers, and the geese from Siberia and Iceland that filled the winter skies of his native Norfolk. Work took him away for 10 years to Bolivia, and then, for another 10, as a guide on wildlife tours to every continent. No sooner did he decide to stop flying, because of the cumulative depth of his carbon footprint, than coronavirus arrived, and work dried up. He decided he would follow the geese all over Norfolk for the winter — on his mother’s old red bike — and explore the role they play in people’s lives. He tells the story of his thousand-mile journey in The Meaning of Geese (Chelsea Green Publishing, p/bk, Sept 21, £12.99). It is, says Nicola Chester (author of On Gallows Down), “a lyrical love letter to North Norfolk… and the gleaming, binding, gossamer threads its geese trail across the globe and back”.

As a schoolboy, Nick Acheson says, he found his flock among birdwatchers, and the geese from Siberia and Iceland that filled the winter skies of his native Norfolk. Work took him away for 10 years to Bolivia, and then, for another 10, as a guide on wildlife tours to every continent. No sooner did he decide to stop flying, because of the cumulative depth of his carbon footprint, than coronavirus arrived, and work dried up. He decided he would follow the geese all over Norfolk for the winter — on his mother’s old red bike — and explore the role they play in people’s lives. He tells the story of his thousand-mile journey in The Meaning of Geese (Chelsea Green Publishing, p/bk, Sept 21, £12.99). It is, says Nicola Chester (author of On Gallows Down), “a lyrical love letter to North Norfolk… and the gleaming, binding, gossamer threads its geese trail across the globe and back”.

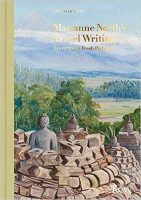

The artist Marianne North (1830–1890) is best known for the vibrant oil paintings of landscapes, trees and flowers that she produced during her extensive travels (recounted in three volumes published after her death) and for the gallery she established at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. In Marianne North’s Travel Writing: Every Step a Fresh Picture (Kew Publishing, October, £28), Michelle Payne, a writer and editor who is currently undertaking a PhD on North, promises to “look beyond misty-eyed romances of the past” and offer a modern perspective on the artist’s life and journeying, “engaging with the colonial aspects of her travels openly and honestly without excuses or denial”. The book will be illustrated with facsimiles of letters and pen sketches North sent to friends, and reproductions of her paintings.

The artist Marianne North (1830–1890) is best known for the vibrant oil paintings of landscapes, trees and flowers that she produced during her extensive travels (recounted in three volumes published after her death) and for the gallery she established at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. In Marianne North’s Travel Writing: Every Step a Fresh Picture (Kew Publishing, October, £28), Michelle Payne, a writer and editor who is currently undertaking a PhD on North, promises to “look beyond misty-eyed romances of the past” and offer a modern perspective on the artist’s life and journeying, “engaging with the colonial aspects of her travels openly and honestly without excuses or denial”. The book will be illustrated with facsimiles of letters and pen sketches North sent to friends, and reproductions of her paintings.

Leave a Reply